From Babylon to Berlin: The rebirth of the Ishtar Gate

Neo-Babylonian | Ishtar Gate | 604-562 BCE | Berlin State Museum | Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin | Image and original data provided by Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz; bpkgate.picturemaxx.com/webgate_cms

Travelers to ancient Babylon were met with an astonishing sight: a gate nearly 50 feet high and 100 feet wide made of jewel-like blue glazed bricks and adorned with bas-relief dragons and young bulls. Dedicated to Ishtar, goddess of fertility, love, and war, the main entrance to the city was constructed for King Nebuchadnezzar II circa 575 BCE.

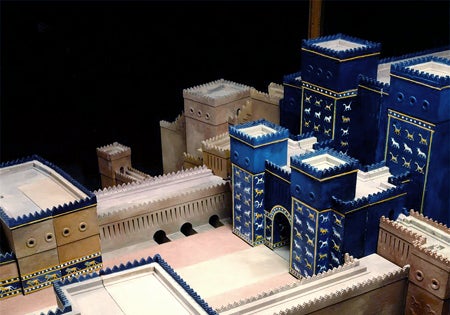

Reconstruction by E. Andrea Hummel | Model of the Processional Way (Aj-ibur-shapu) and Ishtar Gate from the Palace of Nebuchadnezzar II, Babylon | before 1930 of 6th-century BCE layout | Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin | Image and original data provided by Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz; bpkgate.picturemaxx.com/webgate_cms

On New Year’s, statues of Ishtar and other deities would be paraded through the Ishtar Gate and down the Processional Way, a brick-paved corridor more than half a mile long, to the temple of Marduk, Babylon’s patron deity. The Processional Way was paved with red and yellow stones inscribed with a prayer from Nebuchadnezzar to Marduk and flanked by soaring walls of enameled tiles decorated with lions and flowers.

Two Panels with striding lions | 604-562 B.C. | Mesopotamia, Babylon | Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Inevitably, Babylon’s power declined and eventually the structures collapsed and vanished under hundreds of years of desert storms. But colorful fragments of the lion figures would one day lead to the unearthing and rebirth of the Ishtar Gate.

In his account of the excavations, German archaeologist Robert Koldewey wrote, “The discovery of these enameled bricks formed one of the motives for choosing Babylon as a site for excavation. As early as June 1887 I came across brightly colored fragments lying on the ground on the east side of the Kasr. In December 1897 I collected some of these and brought them to Berlin, where the then Director of the Royal Museums, Richard Schöne, recognized their significance. The digging commenced March 26, 1899, with a transverse cut through the east front of the Kasr. The finely colored fragments made their appearance in great numbers, soon followed by the discovery of the eastern of the two parallel walls, the pavement of the processional roadway, and the western wall, which supplied us with the necessary orientation for further excavations.”

Ishtar gate | 7th-6th century BC | Babylon, Iraq | Photographed by Machteld Johanna Mellink| Image © Bryn Mawr College

A reconstruction of the Gate was built in the 1930s from Koldewey’s findings at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, where visitors today can once again admire Nebuchadnezzar’s majestic project.

Search for Ishtar within the Berlin State Museums collection in the Artstor Digital Library to see the structure in the museum, frieze details, and drawings and models of the Gate and the Processional Way. A general search for Ishtar Gate will lead you to images of fragments in other museums, including the Louvre and the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul (via Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as field photography of the site in modern-day Iraq from the World Monuments Fund and Bryn Mawr’s Mellink Archive.