Finding the phenomenal women in fine art

“It’s in the reach of my arms, / The span of my hips, / The stride of my step, / The curl of my lips. / I’m a woman/ Phenomenally. / Phenomenal woman, / That’s me.”

– Maya Angelou

Mickalene Thomas, Don’t Forget About Me (Keri), 2009, exhibited at Lehmann Maupin, Spring 2009. Image and original data provided by Larry Qualls, © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / BILDKUNST, Bonn

Women have long been used as inspiration for art. They have served as muses to both eastern and western culture, and our bodies have been used to represent the power and beauty of nature.

Yet the images of the female body that we see on a daily basis are often passive and hyper-sexualized. Women’s bodies are the go-to sales tactic in popular media and advertising. Yes, you might say, sex sells, but nothings sells as much as our sex sells. Women’s bodies sell beer, cars, perfume, burgers, chewing gum, and even animals rights (yes, you read that correctly – look up PETA’s campaigns) — and of course, the object that all of the women in these advertisements are ultimately selling is themselves.

Furthermore, most pictures of women we see are all the same — tall, thin, and typically white. What’s devastating about seeing the same type of women everywhere is that people start to believe that all women should fit this ideal. As a result, women and children have become hugely dissatisfied with their bodies and undergo a vast amount of violence, both mental and physical, in order to try to fit their bodies into this artificial ideal. In the United States over one-half of teenage girls use unhealthy weight control behaviors. I am not the only woman who hears over and over the phrase, “I look fat.” I also know that I am not the only woman who has spent countless hours at the gym trying to attain a body I saw in a magazine. And this lack of confidence, this obsession with body image is contagious. It festers even among the most confident of women.

Peter Paul Rubens, Venus Before a Mirror, 1614-1615, Liechtenstein Museum (Vienna, Austria). Image and original data provided by Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y., artres.com

During my early years, I saw real women’s bodies. I grew up taking baths with my mom and my younger sister. I know how a mother’s body looks. I also helped my grandmother put on her saris and I know how an aging woman’s body looks. I was also allowed to flip through photo albums of my aunt, and I was never chided when I came across photographs of her nude and pregnant.

Despite those formative years, it’s hard not to feel bad about my body when I am surrounded by so many skewed depictions of women. What can we do? How do we learn to accept our bodies as they are? Is there a way to negate the destructive forces of popular media? I think so.

One thing that’s helped me negate unrealistic images of women is the depiction of women in fine art. Unlike advertisements, the women in art are not all the same. A trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art is all you need to confirm this. And what a relief it is! To see images of women’s bodies that are not only varied, but powerful, thoughtful, and human.

Even more affirming, the body types rejected by the mainstream are the very same bodies of goddesses in both Western and Eastern art. These goddesses look surprisingly like the bodies I grew up seeing. They are not all sharp, angular, and unattainable, but they are real and earthy. Through these statues and paintings, I see more accurate representations of the women around me — my aunts, my sisters, my mother, and myself.

Indian, The Goddess Kali, circa 1775 , site: Rajasthan, Kotah. American Council for Southern Asian Art (ACSAA) Collection (University of Michigan).Photo: © Asian Art Archives, University of Michigan

In many of these works of art, women are not the object but the central character. They are powerful, and seductive, even dangerous. They are depicted as thoughtful, motherly, and human. The image of the goddess Kali from the University of Michigan’s American Council for Southern Asian Art (ACSAA) Collection offers an alternative ideal of the feminine — powerful and terrifying. Kali sits center stage, wielding a sword in one hand and the head of her most recent victim in the other, wearing nothing but a garland of human heads. She is clearly the aggressor, and unlike the women we typically see in the mainstream, she is anything but passive. She encompasses many polarities — both lover and killer, creator and destroyer. She is one to be reckoned with.

Fine Art isn’t just about depicting women as goddesses. There are many female (and male) artists who have acknowledged the marginalized position of women in society and want to change that through their images.

- Eizan, Furyu yusuzumi sanbijin (Three elegant women enjoying the evening cool), circa 1810 – 1820. Image and data from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

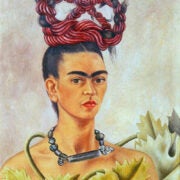

- Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait with Braid, 1941, Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, Vergel Foundation. Image and original data provided by Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y., artres.com

- Jeanette Bernard, three women bathers at the shore, ca. 1910. George Eastman House

As you can see in the image above (courtesy of the Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives), Frida Kahlo paints her own realities. In her portraits she is alluring without being conventionally beautiful. Through the use of symbols (thorn necklaces, blood, tears) she invites you into her world, where she is the master. Her portraits speak. They unabashedly tell stories — her stories — and she demands that you listen.

Art is also a way to bring issues to the fore like body image. For example, Jenny Saville’s paintings reveal the feelings that many women have towards their bodies. As in the example above from the Larry Qualls Archive, she uses a cooler palette and violent brushstrokes to paint bodies like carcasses. She is able to convey the hatred women have towards their bodies when they don’t fit into the commercial mold. She is only one of the many examples of art that works to destroy the illusions that women are passive, objects for sex, and only their bodies.

When we are able to see ourselves accurately depicted in images, we are free from the images imposed on us. We move onward, outside the image. We’re able to focus on actions rather than appearance. We become full characters. This is also why it’s essential for us to have access to art — the fuller truth of who we are and what we can become.

– Ayesha Akhtar, User Services Assistant

The other images in this post come from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Walters Art Museum, and George Eastman House collections in the Artstor Digital Library.