Botticelli, Michelangelo, and the importance of drawing

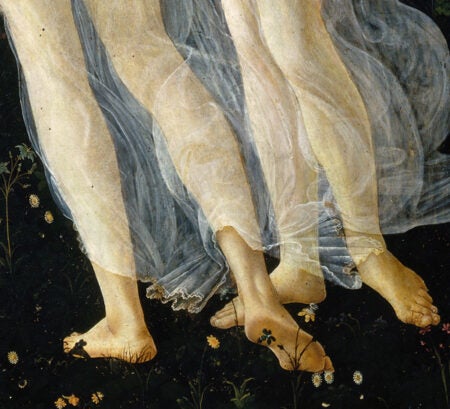

Sandro Botticelli, Primavera; Allegory of Spring, c. 1478, Galleria degli Uffizi. Image and original data provided by ©SCALA, Florence/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.; artres.com; scalarchives.com

Kenyon Cox (1856-1919) might now be best remembered for his murals in the Library of Congress, as well as in the state capitol buildings of Des Moines, St. Paul, and Madison, but he was also a respected writer and influential teacher. In 1911, he delivered a series of lectures on painting at the Art Institute of Chicago, later published as The Classic Point of View. His accessible writing style and his infectious enthusiasm for the Old Masters still speak to us today. Following is an excerpt from his lecture on the importance of drawing, focusing on the work of Botticelli and Michelangelo.

Drawing is a great expressional art and deals with beauty and significance, not with mere fact. Its great masters are the greatest artists that ever lived, and high attainment in it has always been rarer than high attainment in color. Its tools are the line and so much of light and shade as is necessary to convey the sense of bulk and modelling, anything more being something added for its own beauty and expressiveness, not a part of the sources of the draftsman. Its aims are, first, to develop in the highest degree the abstract beauty and significance possessed by lines in themselves, more or less independently of representation; second, to express with the utmost clearness and force the material significance of objects and, especially, of the human body. According as one or the other of these aims predominates we have one or the other of the two great schools into which draftsmen may be divided. These schools may be typified by the greatest masters of each, the school of Botticelli, or the school of pure line; the school of Michelangelo, or the school of significant form. Between these lie all the law and the prophets. Of course no artist ever belonged entirely and exclusively to either school. It is always a matter of balance and the predominance of interest. Even a Botticelli tried to put some significant form inside his beautiful lines, and even Michelangelo gave thought to the abstract beauty of his lines apart from the significant form they bounded.

We are all so much, and so inevitably, bound by the conventions of our own time that to many an art student of today it will seem little less than absurd to call Botticelli a draftsman at all. He could not foreshorten a leg or an arm, but drew them always at full length, exercising great ingenuity, at times, in so arranging his groups as to permit of this full length treatment. His use of light and shade is very restricted and he never gives the illusion of solidity and detachment from the background. His figures are attenuated, never very certain in their structure and articulation, and often faulty in proportion. The modem student, from the height of nearly five centuries of further study, looks down with amused superiority, conscious that all those things which were impossible for Botticelli are commonplace now, and within the power of everyone. And yet the student is no more than a student whose work is not worth the paper it is drawn on — the master remains the master, as unique and unapproachable today as in his own time. The student can place things better — unless he is a rare genius, he will never draw one thousandth part so well.

- Sandro Botticelli, Detail of: Primavera; Allegory of Spring, c. 1478, Galleria degli Uffizi. Image and original data provided by ©SCALA, Florence/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.; artres.com; scalarchives.com

- Sandro Botticelli, Detail of: Primavera; Allegory of Spring, c. 1478, Galleria degli Uffizi. Image and original data provided by ©SCALA, Florence/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.; artres.com; scalarchives.com

A group which shows Botticelli at his best, yet with all or nearly all his shortcomings from our modem point of view, is that of the three Graces from the picture called Primavera. It is flatter than many of his works, the indication of modelling being reduced to the lowest terms, but this is of no consequence whatever. In this kind of art the indication of modelling might be entirely eliminated, leaving the result as flat as Greek vase painting, with no detriment to the essential quality of it. There is no foreshortening, the avoidance of it in the complicated arrangement of the arms being very noticeable. Even the feet are not foreshortened, and, in one of the figures, the toes are turned out beyond the possibility of nature in the effort to avoid this difficulty. But study this lovely arrangement of lovely lines; learn, if you can, to appreciate their flow, their subtlety, their vitality, and inimitable grace, the sense of movement and of life that they convey; observe the delicate stiffness, as of flower-stalks, in the lines of the figures, the swiftness, as of living flame, in the curves of hair or filmy drapery; feel the passionate intensity of the artist, controlled by rigid discipline and refined taste, as his hand follows in its daintiest modulations and finest contrasts this melody of pure line — then you may begin to understand why he is the greatest master of linear drawing in our Western art. For myself, I should rate him the greatest in all art, placing him above even the best that China and Japan have done in a branch of art in which China and Japan have always excelled.

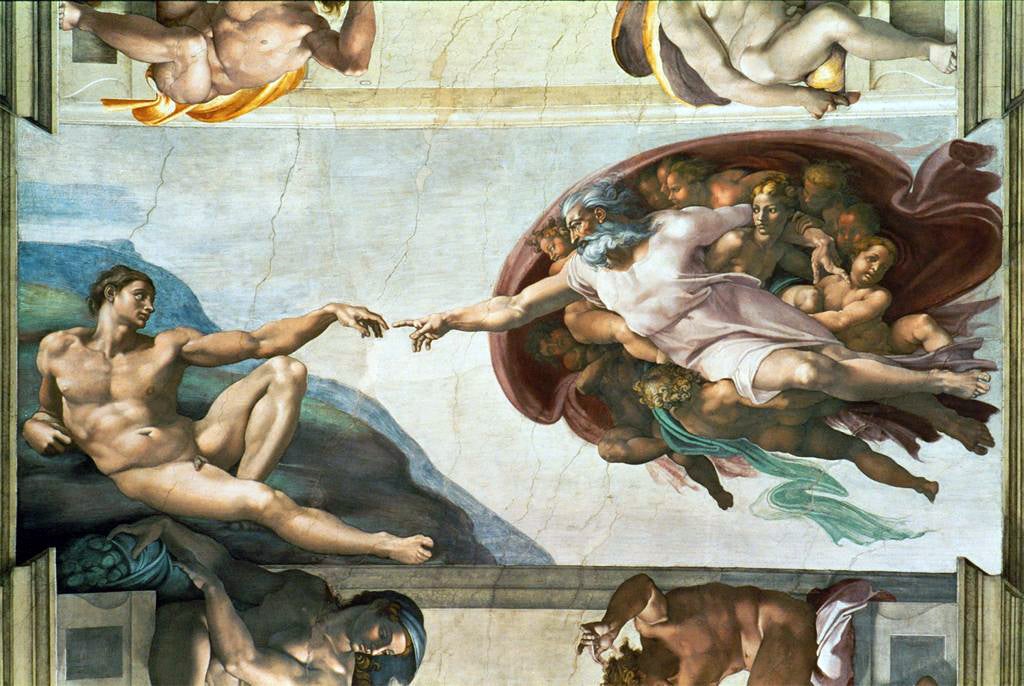

Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel; ceiling frescos; Creation of Adam, 1508-1512, Rome, Italy. Image and original data provided by Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y., artres.com

The drawing of Michelangelo is entirely different from this. He came at the end of a long succession of artists who had striven to master the significance of the human figure, and he resumed everything they had learned. He is almost too fond of foreshortening, using it sometimes, one suspects, merely to display his mastery of it; and his drawing is so far from flat that it depends more on modelling and on interior markings than on the contour. He is a draftsman, not a chiaroscurist or a colorist, therefore he does not drown his forms in light and shadow or lose his edges in the mystery of atmosphere, but you may see many a drawing of his in which the form is hatched into existence with pen or crayon lines like the strokes of a sculptor’s chisel, everything being determined except the final outline. He cared little for mere correctness, indulging in any exaggeration that would enhance the sense of bulk and structure which he wished to convey, and the habit of exaggeration grew upon him while the restraint of direct study from nature operated less and less, so that in his latest paintings the human figure becomes swollen into something almost monstrous, however titanic in its expression of energy. To have him at his best you must take him not only before the Last Judgment but before the Prophets and Sibyls — you must take him in the great central panels of the Sistine Ceiling. There, in such a composition as the Creation of Adam, you have the highest reach of constructive figure drawing, as in the Primavera you have the standard of pure linear expression.

- Michelangelo, Detail of: Sistine Chapel; ceiling frescos; Creation of Adam, 1508-1512, Rome, Italy. Image and original data provided by Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y., artres.com

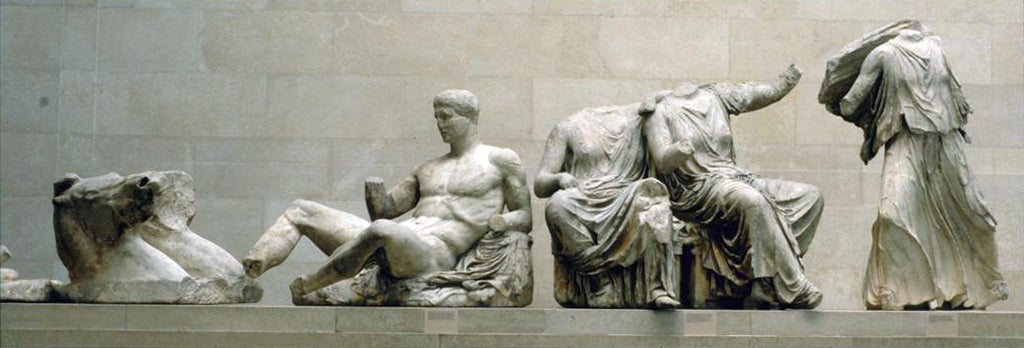

There is magnificent line in this fresco, also, the sweeping movement of the Creator and his attendant spirits being attained in the only way in which motion ever has been attained in painting — by composition of line. But all that can be told by line— even the difference between the energetic, pointing finger of the Almighty and the limp hand of the half-awakened Adam — is subordinate to the realization of these two figures as solid objects in space, to the expression of their structure as human bodies made of bone and muscle, and of the stresses and interactions of these bones and muscles as affected by position and movement. What particularly concerned Michelangelo was the roll of Adam’s mighty thorax upon his pelvis; the forcing upward of his right shoulder on which his weight rests, and the elongation of the left pectoral by the stretching of the arm; the strain on the muscles of the neck caused by the turn of the head, and the swelling and flattening of thigh and calf in the bent leg. As an ideal yet real presentation of the human figure, magnificently explicit in the rendering of all significant detail, but from which everything accidental or insignificant has been purged away, there is nothing like this in painting, and nothing in any art except the sublime figures from the pediment of the Parthenon.

Greek, Parthenon: E. pediment: Helios Chariot, Dionysos (or Herakles?); Demeter, Kore, and Artemis (or Hestia, Dione, and Aphrodite?), ca. 438-432 B.C.E. Catalogued by: Art Images for College Teaching

But why all this interest in the human body? Well, in the first place, because the great figure artists are made so, and nothing else seems to them so beautiful or so significant. And because meanings and intentions can be conveyed by figure drawing that can be conveyed in no other way. These movements and stresses of the figure communicate themselves to you, and you feel them in your own body, thereby attaining a sense of power and freedom you are never likely to get from anything else; and they put you into the mood of the being who displays them and make you, by the state of the body, divine the state of the soul. For, in the hands of a master, the body is infinitely more expressive than the face, and the art of figure drawing is one of the most intellectual and expressional of the arts.

Kenyon Cox, Composition sketch for allegory of USA, Cleveland Museum of Art. Image and original data provided by the Gernsheim Photographic Corpus of Drawings