Cross-cultural cross-sections: Student curators shed light on architectural collections

Charlotte Perriand, La Maison du jeune homme, Brussels, Belgium, 1935, © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris, Data source: Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, Columbia University and Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

An interview with the graduate student curators of Avery/GSAPP Architectural Plans and Sections

To celebrate the completion of our two-year collaborative project with Avery Library and GSAPP on releasing a collection of 20,000 architectural plans, sections, and related materials in Artstor, Lisa Gavell, Artstor’s Senior Manager of Metadata & Content, spoke with five of the graduate student co-curators who contributed to the project: Sabrina Barker, Serena Li, Ernest Pang, involved from the beginning of the project, as well as Sharon Leung and Ayesha S. Ghosh. Working with Avery staff, they pored over a vast array of Avery’s holdings in order to compile a selection that reflects the most important modernist architectural works of the 20th and 21st centuries. The result is a resource of essential documentation of modern architecture, shared online for the first time.

Avery is one of the largest architecture libraries in the world. What was it like to cull through such an extensive collection, with the aim of providing the essentials?

Sharon Leung: Thankfully the project’s goal was to focus on 20th century architectural canons. Although Avery has a lot of material prior to and after this time, the essentials were based primarily on material covered in our core history classes. Historians Kenneth Frampton and Mary McLeod offered their expertise in the time period and guided us personally, but also through their course syllabi.

Ernest Pang: Sharon is right. I would add that at Columbia, we benefited from a robust curriculum in architectural history – a core curriculum of which shared some uncanny structural similarities with that of the Analysis and Theory seminars taught by Anthony Vidler and Kenneth Frampton at Princeton in the ’60s or ’70s, which helped develop ideas and frameworks that have shaped our present understanding and pedagogy of modern architecture. This is an indirect way to suggest how architectural canons are made by historians and people, not given by publishers, and the richness and diversity of the canon is an additive (or subtractive) process by different people who look to examine and aim to describe the desires, motives, and ideologies behind the work from a given time frame, geographical locale, and/or cultural framework. Culling through an extensive collection began with determining a scope; and based on that scope we would gather works that would either express or add additional information regarding the values, ideologies, even anxieties that were relevant of that period or geopolitical region–ultimately, by relying heavily on the expertise and scholarship of Columbia’s faculty and Avery’s extensive resources.

Ayesha S. Ghosh: In addition, in Phase 2 we were bolstered with the methodology established for the first phase and were able to be more precise with the areas we were trying to add to the collection, for example including more Latin American and Japanese projects to expand and add diversity to the existing collection. Finding the right materials for these books was possible with the syllabi of other professors, as well as students who worked in the Visual Resources Collection who were able to translate the critical information for these projects from other languages.

You were all knee-deep in images and data. What was your most surprising discovery along the way?

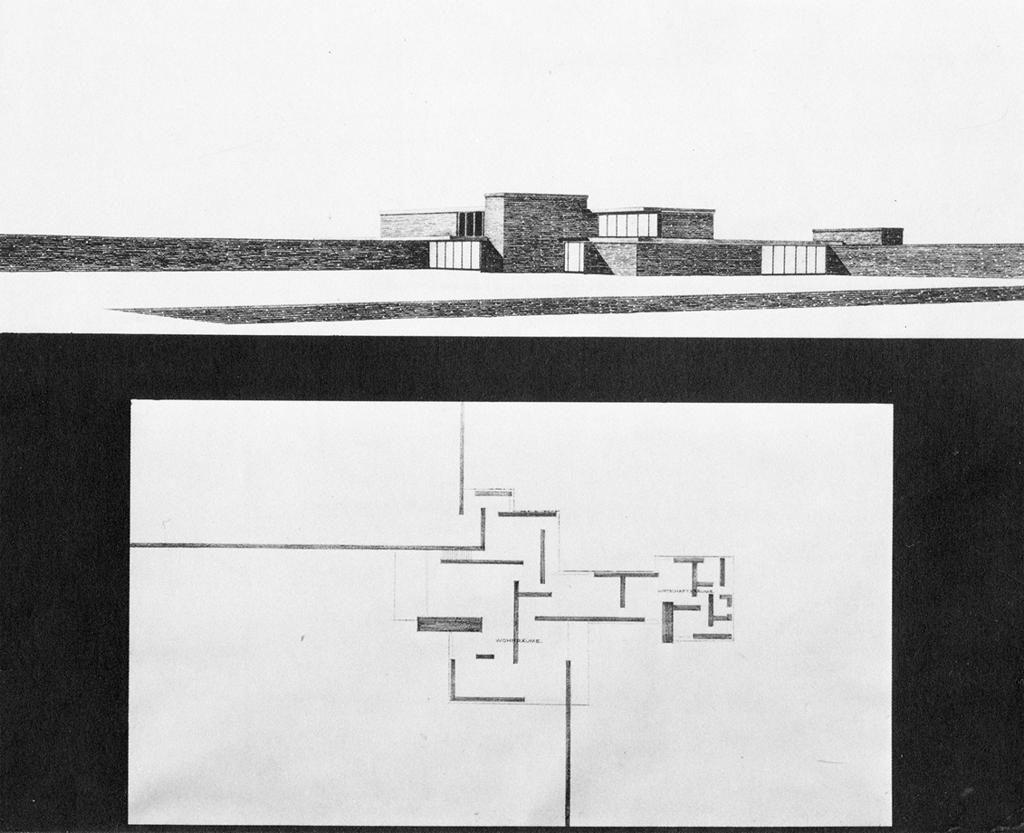

Sharon Leung: Some of the most surprising discoveries were in the unbuilt projects. So much focus is given to the final product, the finished building in architecture school. However, many architects have more unbuilt work than built work in their résumes. Even seeing the number of works Mies van der Rohe never realized is quite shocking. And sometimes the unbuilt work carries much more idealistic, manifesto-like thinking and should not be dismissed solely on the criteria of being built.

Ernest Pang: Additionally, though not necessarily surprising, we were continually reminded as architectural students by the fecundity and richness of the modern architectural thought and projects; in particular, we were reminded of the notion that the themes and tropes of this body of work that present-day architects, architectural historians and students pretend to discover were eloquently articulated once before.

Of course, there would always be those moments where you would come across gems that you would fall in love with.

Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe, Brick Country House (unbuilt), 1924, Data source: Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, Columbia University and Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

What’s your favorite image or project?

Sabrina Barker: The VRC is home to an extensive collection of lantern slides, which William Ware began in 1881 when he created the school of architecture at Columbia. The collection continued to grow until 35mm slides began to replace them, probably around the 1940’s. We have about 25,000 of these lantern slides sitting in boxes in the VRC, and what I think is really fascinating about them is that they represent the advent of architectural education through images. In 2010 the VRC did an exhibition of some of these lantern slides, which actually still exists in the basement of Avery Library, and also proposed a project to clean, scan and catalogue the entire collection. Unfortunately the VRC was unable to realize the project at that time, but I think it remains a worthwhile endeavor. Generations of architects and historians learned from the images projected from that collection, and it would be fascinating to see how those early images have shaped our own dialogue of architectural history.

Ayesha S. Ghosh: Producing images for Artstor, and particularly having the task of reviewing images to be added to the collection, led to an exposure of countless architects, projects, models and drawings I would never have had the opportunity to see otherwise. One of my favorite images is a look into a model of New Babylon by Constant Nieuwenhuys. I had never seen that view of the model, in a view that was more on a human scale than a schematic, or urban. I found the image so powerful, it ultimately influenced the direction I was taking for my studio project that semester. The idea of encountering the unexpected or unseen is what makes the collection so invaluable.

A staggering amount of work went into this project: more than 15 graduate students were involved throughout the course. Diversity seems to be a common current of this collaboration–that of disciplines, talents and interests of the staff. Can you say a little more about the interdisciplinary nature of the collaboration?

Sabrina Barker: Serena and I had our first meeting with Avery Library in the Summer of 2014 and I remember distinctly feeling that we had just signed up for an impossible task… this project asked us to scan 20,000 images in two years, as well as set up a system that could accurately organize and export all of the data and provide it to Artstor.

Sharon Leung: Really, this project belongs to our diligent team at the Visual Resources Collection! 50% of the students entering the masters of architecture program do not have a background in architecture, and I would say also 50% of students are international. Geographically, our team has covered the globe, and it is evident in our collection. Non-western projects were held in the same regard as western projects.

Serena Li: Most of the team at the Visual Resources Collection were Master of Architecture students, but about a third represented other disciplines or were dual degree students within the graduate school. Together, the team included students from architecture, urban planning, historic preservation, and real estate. On occasion, we also had to rely on foreign language speakers in the group to translate relevant text and captions from an original source. The project was large enough that students with specific interests or talent could pursue dedicated roles on the team: those with a special love and knowledge of architectural history spent more time in Avery poring through the catalog and finding material for the collection, while those who gravitated toward the technological work spent time maintaining and modifying the database infrastructure. Everyone who worked on the team spent time scanning and cataloging, as this was the bulk of person-hours spent on the project. There was always a large stack of books in the room with images flagged for inclusion in the collection, so students also gravitated toward their favorite topics when they chose the next book to scan and catalog from the queue. This was a great way to learn more about architectural history and precedents outside of class, and it was always fun to see someone call others over when they stumbled upon something they wanted to share.

Ayesha S. Ghosh: It was incredible to see how the team not only adapted to their positions each semester, but how invested and cohesive the team always was. Adding each image to the collection was laborious from finding the right images to making sure it met our standards to be added to the database. Each person was so invested in our mission to make sure we were doing it right that the collaborative energy brought it together, from helping with translations to reviewing each other’s work with openness to make adjustments.

- Le Corbusier, Chandigarh, India, 1957-1965, Data source: Data source: Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, Columbia University and Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

I noticed a few photos documenting construction. Do you foresee any of the content offering new perspectives to the field?

Sharon Leung: Construction photos give any built project perspective of forces that were present at the time. It offers a way into seeing how architecture is part of a larger set of technological and cultural vectors. We tried to include construction photos to provide context and insight to each project if possible. We like the idea that these images of documentation might provide a way into seeing new interpretations of the final project.

Sabrina Barker: The way in which our buildings are constructed and their surrounding physical context tells a larger story than the perfectly framed image of the finished project. Our goal for this collection was to offer a more complete selection of images for each of the chosen projects than simply the famous images that you can find when you search for a building on Google. We hope that by including a wider range of images for each project we can expand the dialogue around each one and maybe even offer a new perspective on a well-known project.

This project focused mainly on modernist architecture. Are there any plans for future projects? What other projects would you like to see covered?

Serena Li: It’s difficult to understand the context for this era of architecture without the inclusion of the history that led up to these works. Even when we began this project, Professor McLeod was already hoping to collaborate with Artstor again on another project to catalog works between the Renaissance and the 20th century. Personally, I would also love to see many earlier works from non-Western sources. I feel that as our world continues to globalize, it is an important time to return to lessons already learned in past, with geographically specific projects that utilize local materials in a climate and context-sensitive manner.

Ayesha S. Ghosh: I agree with Serena, expanding to include pre-18th century architecture and more global projects would benefit in creating a more inclusive narrative for architecture history. Even with the focus on modernist architecture, it was apparent that we were not including many interesting projects in places such as India, China, and other non-western nations. While we included many Brazilian modernist projects, I think it was a brief survey of a long and rich history of architecture that, if made comprehensively available, would be useful to a wide audience.Occasionally, the projects we selected were more contemporary as well. It would be interesting to include more as they’re indicative of building practices and an architectural ethos that many students and practitioners are a part of today.

Ernest Pang: In addition to considering the areas that would provide a more comprehensive and complete picture of architectural production across time and the world, we might also explicitly think about the questions or issues that we want those areas to address. For example, one of the things we quietly tried to address within the canon of 20th-century modernism is the role of women in architecture, by choosing works by important women architects like Eileen Gray, Natalie de Blois, Margarete Lihotzky, and Charlotte Perriand. This is in part the influence of Mary McLeod and Gwendolyn Wright, who along with many accomplished scholars, have articulated the role, contribution and legacy of women architects in a narrative that is dominantly white and male. More documentation is needed. Speaking of white and male, one may also look at (post-)colonialism and architecture. Such subject areas, if not under represented, are most definitely unevenly represented and need additional articulation. In contrast to the autonomous architectural object, developments in regions profoundly affected in the past by colonialism have been the grounds for new phenomena, like megacities and extreme rapid urban development. One goes back to the question of how might a digital library like Artstor help us understand and inform us of these phenomena and issues.

An undertaking this large and complex clearly called for quite a bit of data wizardry. Was an existing content management system used, or a new one implemented?

Serena Li: We toyed with the idea of switching to a new content management software, but chose to continue with a heavily overhauled implementation of what we already had. We converted our digital catalog from a table of hand-typed data into a relational database system that allowed us to link individual images to entries in other tables of buildings, architects, and locations that were consistent with other standardized catalogs. This greatly reduced errors in human data entry, and allowed us to be consistent in documenting single entities that went by multiple names–Le Corbusier vs Charles Edouard Jeanneret, for example. We also had to keep careful track of the process, such as all the projects we intended to document, whether they had been researched at the library, which books we had prepared for the catalog, checked out or returned at any given point, whether each asset in our catalog was destined for the Artstor collection, and whether they had passed final curatorial inspection or needed to be sent back to meet data or image quality standards. We spent the first two or three months of the project on this rebuild of our technical infrastructure and cataloging a series of test images along the way to test this new system. Our goal was to hone in on a high-speed workflow that would not compromise on quality of data or image capture.

Sabrina Barker: I have to add here that we were incredibly lucky to have Serena working on this project during its first year, as she brought with her an extensive knowledge of computer programming and database management that is unusual at a school of architecture. Before Serena reworked our entire database structure it was common to find the same project with six or seven different variations in name, location, and date. Her ability to manage the work required for getting the database in shape allowed the rest of the team to focus their efforts on image quality and the curation of the images.

View the collection in JSTOR.