Seeing is believing: early war photography

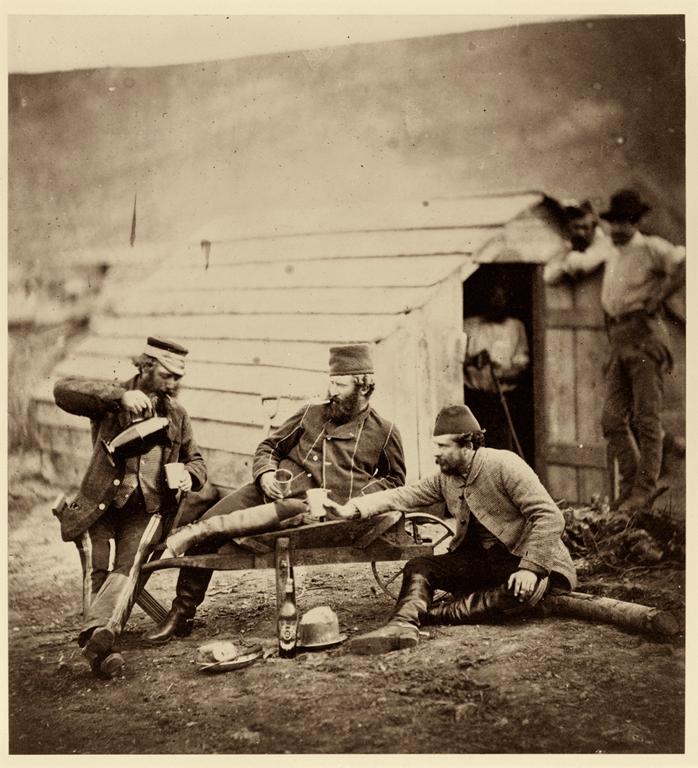

Roger Fenton, Hardships in the Camp, 1855. Image courtesy of George Eastman House www.eastmanhouse.org

When it comes to modern warfare, we’ve seen so much through photographs: mass graves, explosions, the faces of soldiers the instant they’re shot. And we’ve also seen the aftermath of war–devastated landscapes, soldiers carrying their dead, and returning home to their families. We’ve become accustomed to a depth of visual coverage that has brought deep familiarity with the realities of war from start to finish, a stark contrast to the experience of civilian audiences prior to the advent of photography. Photographs from three wars fought within an eighteen year period–the Mexican-American War, the Crimean War, and the American Civil War–illustrate the changes in photographic techniques, coverage, and distribution that would eventually develop into the prolific (and explicit) creation and distribution of war imagery we see today.

Unknown photographer, General Wool and staff in the Calle Real, Saltillo, Mexico, ca. 1847. Image courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art www.cartermuseum.org/collection

Unknown photographer, Burial site of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Clay, Jr., ca. 1847. Image courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art www.cartermuseum.org/collection

The first photographs of war were made in 1847, when an unknown American photographer produced a series of fifty daguerreotypes depicting scenes from the Mexican-American war in Saltillo, Mexico. These images covered a range of subjects, from portraits of generals and infantrymen to landscapes, street scenes, and post-battle burial grounds. While the images provide insight into daily life on the periphery of the war, they are especially notable for what they do not depict: in them, we see neither active battles or wounded and dead bodies, nor the idealization and glory sometimes associated with war.

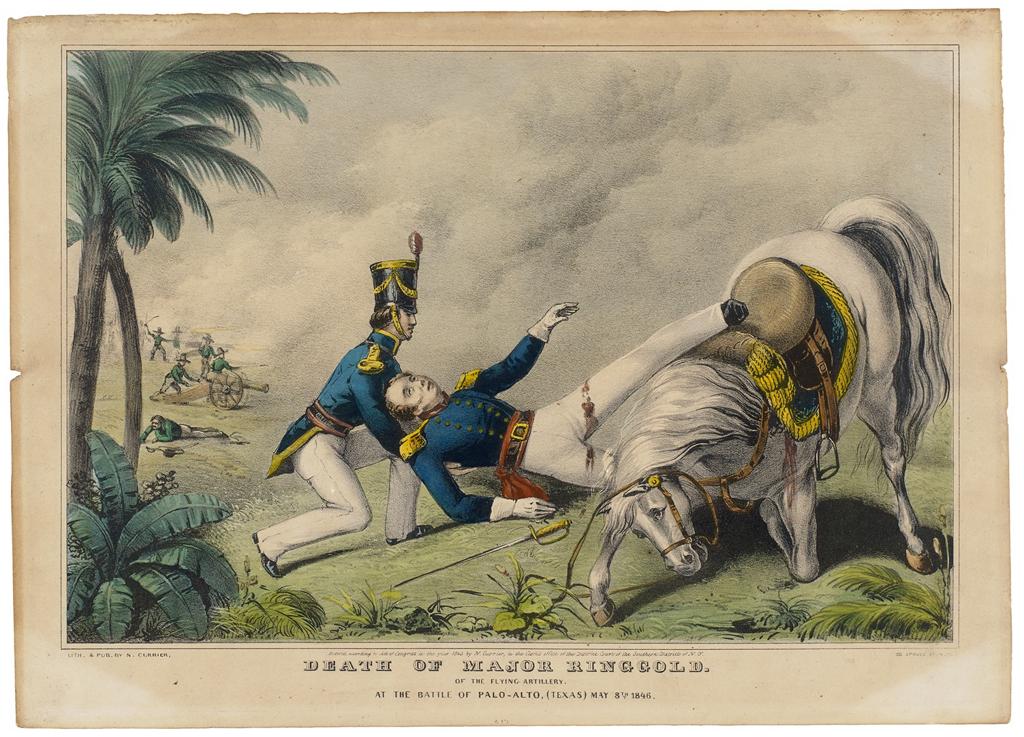

Nathaniel Currier, Death of Major Ringgold, 1846. Photograph © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

In The Emergence of Modern War Imagery in Early Photography, Bernd Hüppauf writes “It can be argued that after hundreds of years of battle painting which, with few exceptions, was devoted to heroic images of war, it was the ‘democratization of images’ through photography from the mid-nineteenth century onward that exposed the moral question of war as one of pictorial representation.” The anonymous photographer’s stylistic choices would have been determined by personal safety and technological limitations of the time. Daguerreotypes were laborious to produce, endangering the photographer in battles, and exposure times ranging from several seconds to many minutes rendered moving subjects as mere blurs. However, the lack of action or heroism found in these anonymous photographs represented a departure from tropes of war imagery that would redefine war as seen by the public. Until the eye of the camera was turned on war, prints, drawings, and paintings fulfilled the need to document such happenings, generally representing them as action-oriented, clean, and heroic undertakings, as seen in the example of the above Currier & Ives print depicting the impossibly pristine death of Major Ringgold during the Battle of Palo Alto. Little attention was given to the realities of death or soldier experiences between battles.

It should be noted that the daguerreotype process had one more limitation that makes these images rather unique within the history of war photography: produced using polished silver-coated copper sheets exposed with mercury vapors, the process yielded a single, mirror-like positive image which could not be reproduced. Small and encased in glass for protection of their delicate, mirror-like surface, daguerreotypes were precious objects rather than devices that could efficiently distribute information to the masses. The first attempt to photograph a war was not necessarily done with journalistic intentions–though this would change in future conflicts.

When the Crimean war began six years later in 1853, photography’s usefulness as a means of documenting, sharing, and digesting ‘factual’ knowledge of historic events was widely acknowledged. Harnessing the power of the realism perceived in photography to shape public opinion, the British government sought to document the war as a means of uniting the public behind their increasingly unpopular war efforts. Four official photographers were dispatched at different points in the conflict, although the fruits of their efforts were lost–many before even making it into public distribution.

Roger Fenton, Valley of the Shadow of Death, April 23, 1855. Image and original data provided by The J. Paul Getty Museum www.getty.edu

The Crimean war wasn’t successfully documented until publisher William Agnew saw an opportunity to sell photographs of the conflict to a concerned public and hired Roger Fenton to document the war. Over the course of four months Fenton created 360 glass plate negatives of battlefield landscapes, staged group portraits of British, French, and Turkish soldiers and their lives in the camps, and generals mounted on horseback, working under the protection of the British government. Much like the images captured by the anonymous photographer documenting the Mexican-American war, there is a notable absence of death and tempering of suffering in much of Fenton’s work. The Valley of the Shadow of Death, one of Fenton’s best-known images from the conflict, indirectly portrays the horrors experienced by troops undergoing heavy fire via a road covered heavily with cannonballs. It is widely accepted that Fenton staged this photograph, moving additional cannonballs into the road to emphasize the horrific bombardment experienced by troops marching the road days earlier, rather than documenting casualties of the attack. We don’t know why Fenton avoided documenting the grisly scenes he likely encountered, opting instead to allude to them through carefully crafted visual symbolism.

Ultimately, sales of Fenton’s body of work weren’t as successful as Agnew expected. In his descriptive background for the Library of Congress’s Fenton collection, cataloger Woody Woodis posits that “the vivid, though understated, reality of war presented in the photographs may have led to a negative reaction by the viewing public, which ignored the aesthetic and technical qualities inherent in the photographs.”

![Alexander Gardner, Home of a rebel sharpshooter, Gettysburg, 1863. Collection [of] Eastman House, Rochester, New York, image courtesy of the Carnegie Arts of the United States Collection.](https://about.jstor.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/6_carnegie_2680006-e1478887984189.jpg?w=500)

Alexander Gardner, Home of a rebel sharpshooter, Gettysburg, 1863. Collection [of] Eastman House, Rochester, New York, image courtesy of the Carnegie Arts of the United States Collection.

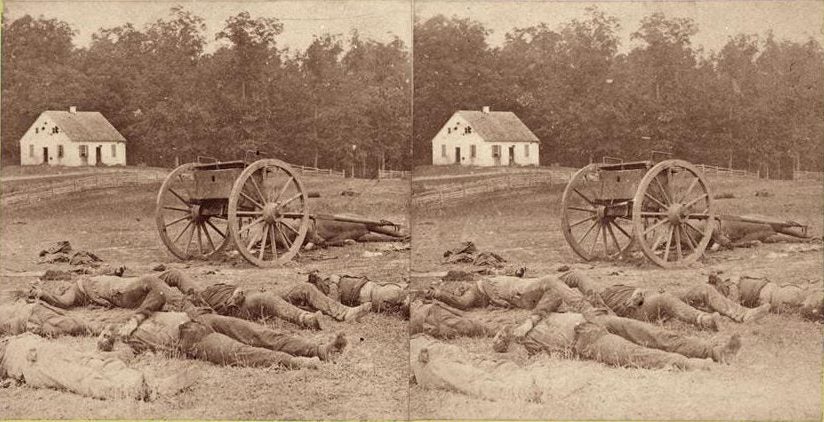

Timothy H. O’Sullivan, A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, July, 1863. Image courtesy of George Eastman House www.eastmanhouse.org

In contrast to the limited documentation and lack of surviving images of the Crimean War, the American Civil War would become the most photographed war of the 19th century, with an enormous body of work surviving the conflict. Coverage of this war differed greatly from earlier efforts in terms of content and distribution of images. The Civil War represented the first attempt to document a war broadly and systematically, spurred by the public’s insatiable appetite for photographs.

Interestingly, Agnew’s vision of mass-produced war imagery for consumption by the general public was realized at scale during the Civil War by other businessmen such as photographers Matthew Brady and Alexander Garner, who employed troops of photographers sent on assignment to document the war as it raged across the country. Joined by numerous individuals on both sides of the conflict, they collectively documented many of the same types of scenes created by previous war photographers and added two key additions to the lexicon of war photography: images of the dead in the aftermath of battles, and the first images of active combat, taken from a distance as warships approached Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. As in many of Fenton’s images, the photographers of the American Civil War enhanced their images, moving bodies and adding props in order to create more compelling scenes. A famed example is found in Alexander Gardner’s Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, in which he posed a fallen body with his own rifle to create a narrative around the death of a Confederate soldier.

Alexander Gardner, Completely Silenced! (Dead Confederate Soldiers at Antietam), 1862. Image courtesy of George Eastman House www.eastmanhouse.org

Commercial distribution of Civil War images proved much more successful with the American public than Agnew’s attempts to sell images of the Crimean war. Prints were widely available for sale in shops around the country, and some photographers made their work available in comprehensive albums, such as Alexander Gardner’s Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War. Stereographs, paired images taken from slightly differing angles to produce a three-dimensional effect when viewed through a stereoscopic viewer, were an especially popular form of entertainment during the Civil War. Most middle-class homes owned a viewer through which the family could marvel as images of the Civil War (and other scenes) sprung to life.

The twentieth century ushered in an explosion of graphic war images, and despite new wars and changing techniques, the critical issues surrounding war photography raised during its earliest days have remained much the same. In War Photography in the Twentieth Century: A Short Critical History, Jason Francisco writes that “photographs became a primary and uniquely powerful form of media widely recognized as crucial to the war effort.” Magazines such as LIFE were dedicated to the proliferation of war images, continuing a similar (although more expansive and intentional) distribution process to that seen during the Civil War. Today, the avenues through which we consume war imagery are even more rapid: the internet has given us instant access not just to official imagery, but to the work of citizen photojournalists and the sometimes shocking imagery produced by our opponents in combat.

War photography provides us with the opportunity to learn about war from the safety of our homes. It engenders knowledge, understanding, and empathy, but also desensitization.

The images in this post are available in the Artstor Digital Library courtesy of the George Eastman House , the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and the Carnegie Arts of the United States collection.