Is Velázquez’s Las Meninas a time-traveling optical illusion?

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, or the Family of Philip IV, 1656. Image and original data provided by Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. www.artres.com

According to a 1985 Illustrated London News poll of artists and critics, Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas was voted the world’s greatest painting.

Let’s take a close look at the painting, its history, and the emotions it elicits to pinpoint why.

Who is in the painting?

- Ankai Tankai Caves; Cave 1; 12th century; Image: 2003; Maharashtra, India. Image and original data provided by David Efurd © David Efurd

Translated to English, “Las Meninas” means “The Maids of Honor.” If you look above at Velázquez’s 1656 painting, you can see that the “maids of honor,” or more accurately the “ladies in waiting,” are actually the two older girls dressing the younger one in the foreground—who happens to be the Infanta Margarita. The Infanta (who would grow up to become the Holy Roman Empress, German Queen, Archduchess consort of Austria, and Queen consort of Hungary and Bohemia) is the daughter of King Philip IV of seventeenth century Spain and his second wife, Queen Mariana.

Standing next to the princess are her two dwarfs and her mastiff. The closest dwarf is actually a male, clothed in a woman’s dress for the Infanta Margarita’s entertainment. The two older women in the background are members of the king’s courtier party, keeping an eye on the princess. In the doorway is José Nieto de Velázquez, another courtier to the king.

- Diego Velázquez, Detail from Las Meninas. Image and original data provided by Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y. www.artres.com

Luminously pictured in what appears to be a mirror on the wall (but may be a painting, which we’ll talk about later) are King Philip IV and Queen Mariana. Las Meninas is set in Velázquez’s own studio, hinted at by the other paintings hanging on the walls—works by Peter Paul Rubens, the master painter whom Velázquez met in 1628 and was known to admire. The man at the easel is Velázquez himself (some might even argue this was history’s first photo bomb.)

Why was it painted?

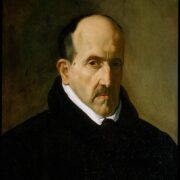

What set the circumstances for Velázquez to paint the masterpiece that many consider the culmination of his career is simply patronage. Prior to meeting King Philip IV, Velázquez traveled from his home in Seville to Madrid in 1622 and painted a portrait of the poet Luis de Góngora. Later that year, the Count-Duke Olivares summoned Velázquez back to paint a portrait of King Philip IV. He was then appointed one of the king’s court painters. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Art, Philip even went so far as to declare that “only Velázquez should paint his portrait.” And thus, the Spanish king became Velázquez’s patron.

- Diego Velázquez, Luis de Gongora y Argote, 1622. Image © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Technique and Style

With Velázquez’s appointment as a court artist came a change in his artwork. His early style was more religiously tinged, painting portraits using naturalistic techniques, but also using light to imply a mysterious spiritual quality. After beginning his work for King Philip IV, he eliminated religion and allegory to primarily be a portraitist concerned with the reality of appearances.He humanized the king and his courtiers in his paintings with natural poses while still keeping them majestic and decorous—so much so that his techniques were notably different and more acclaimed than any other Spanish court artist. As Velázquez aged, his brushwork loosened, becoming very free (perhaps influenced by his two trips to Italy). Along with this transition, he started to paint King Philip IV’s new and young Queen Mariana of Austria and the royal children. This all led to Las Meninas.

However, Las Meninas is not Velázquez’s most famous painting solely for showing King Philip IV, Queen Mariana, the Infanta Margarita, and other courtiers as naturally as possible.

Is Las Meninas a time-traveling optical illusion?

There’s no doubt that the most striking thing about Las Meninas is its unique perspective. We are immediately drawn in by the stares of the royal child, her dwarf, and Velázquez himself at his easel, brush in hand. At first glance, it seems that we are a component of the painting and that Velázquez is painting us, the viewers. But then, if we move our focus to the background, we see that King Philip IV and Queen Mariana are pictured on the wall, and we don’t know if their framed likeness is just another painting or if it’s supposed to be a mirror reflecting that they—not we—are the subjects of the painting. There’s also a theory that the painting’s “fourth wall” is actually not being broken at all—that Velázquez was just painting what he saw on a large floor-to-ceiling mirror, which could explain why so much space in the work is devoted to the ceiling.

Visually, it stuns us; are we in the work or are we not?

Rationally, we know we can’t be in a painting from 1656. But through Velázquez’s unprecedented self-reflexive (dare I say, postmodern) approach, Las Meninas becomes an optical illusion because onlookers can’t determine where to place themselves in relation to it. This, combined with its realistic style, pulls us—almost literally—into a seventeenth century court painter’s studio.

Las Meninas is not an artifact of symbolism, nor does it have any deep allegorical meaning regarding religion or societal issues. The “world’s greatest painting” is in fact just a portrayal of true life during its time period. But since it aims to make viewers unsure of where they are, it becomes much more powerful and unforgettable. Velázquez may very well have known that the best way to capture an audience is to play on our sense of self, for we all pay more attention to things that directly involve us. In Las Meninas, through the combination of optical illusion and the realistic portrayal of history, we see ourselves as part of a historical masterpiece, and thus it becomes etched into our minds.

– Stephanie Grossman

Marketing Associate

Sources

Chilvers, I., & Osborne, H. (Eds.). (1988). The oxford dictionary of art. England: Oxford University Press.

Gowing, L. (Ed.). (1995). A biographical dictionary of artists. England: Adromeda Oxford Limited.

Gowing, L. (Ed.). (1983). The encyclopedia of visual art. USA: Prentice Hall.

Kleinbauer, W.E., & Slavens, T.P. (1982). Research guide to the history of western art. Chicago: ALA.

You might be also interested in:

A closer look at Hans Holbein’s “The Ambassadors”