Frederic Edwin Church’s The Icebergs and the tragedy of the Arctic sublime

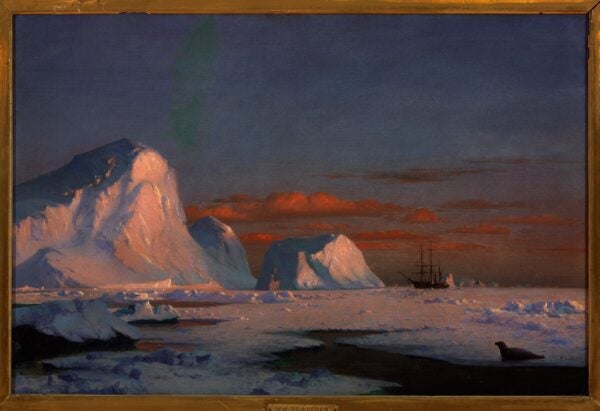

Frederic Edwin Church, The Icebergs, 1861. Image and original data provided by the Dallas Museum of Art

The search for the Northwest passage, an arctic maritime route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, drove European exploration of the North for hundreds of years. The search was exceedingly treacherous–pack ice, the floating ice covering the sea, made arctic waters impassable throughout most of the year and explorers perished in harsh conditions–but the danger and beauty of the unknown North enchanted an adventure-hungry public. Artists were similarly enamored, creating resplendent paintings that represented a sublime view of an Arctic that has gradually crumbled (or more accurately, melted) over the past century as global warming wreaks havoc on the icy seas.

Arctic exploration surged in the nineteenth century, as did the public appetite for news related to the North. However, official accounts of northern voyages were rather dry. As Richard Bevis writes in Road to Egdon Heath: the Aesthetics of the Great in Nature, “accounts of expeditions offered no more emotional and imaginative sustenance than in Captain Cook’s time; the leaders did not create the arctic sublime […] that fascinated the public. Rather, people were stimulated by the ideas and images of the North.” While the public enjoyed the firsthand records and sketches explorers published of their experiences in the Arctic, it was the artistic and literary interpretations that truly captured their imagination and elevated arctic exploration to a national obsession in Great Britain and America. Writers such as Mary Shelley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Edgar Allen Poe brought the Arctic to life through fictional works. Many artists used explorers’ writings and drawings to shape their paintings and lithographs, such as the Arctic scene below from the Gernsheim Photographic Corpus of Drawings. Other more adventurous artists, such as Frederic Edwin Church and William Bradford, joined exhibitions or chartered their own, delighting their audiences with icy landscapes of astonishing blues, purples, and golds.

James Hamilton, Arctic scene, after Dr. EK Kane, an ice floe in the Polar Sea, 19th Century, British Museum. Image and original data provided by the Gernsheim Photographic Corpus of Drawings

The mid-century Franklin Exhibition had a profound effect on the way Europeans and Americans conceptualized the Arctic. Departing England in May of 1845, 129 men led by Sir John Franklin sought to become the first expedition to traverse previously untraveled portions of the fabled Northwest Passage. When Franklin did not return by 1848, search parties were dispatched and the mystery of the crew’s fate became a public concern. Between 1848 and 1878, a total of 20 expeditions from Great Britain and America set out in search of Franklin and his men. A grim tale began to unfold through cumulative discoveries: months after setting sail, Franklin’s two ships, HMS Terror and HMS Erebus, were trapped in sea ice and abandoned by the crew, who were believed to have been suffering from lead poisoning caused by poorly soldered food tins. Stranded and already weakened, they slowly succumbed to scurvy and starvation, ultimately resorting to cannibalizing their dead. All 129 men were lost.

While exploration of the Arctic was always known to be perilous, the disappearance of the Franklin Expedition affected the public’s romanticized notions of the region, and the slow stream of increasingly somber discoveries kept the tragedy fresh in the minds of the British and American publics. The horrifying deaths of the Franklin men underscored the hostility of the untouched northern landscape, and many artists responded to the loss by introducing obvious allusions to danger in their arctic scenes.

Frederick Edwin Church’s luminous painting The Icebergs (in Artstor courtesy of the Dallas Museum of Art) exemplifies this change in perception. The monumental painting was created and first exhibited in 1861, but two years later Church modified it to include a broken ship’s mast in the foreground as a reminder of the powerlessness of man–specifically, Franklin and his crew–in the face of the vast, inhospitable arctic landscape. It is important to note that nineteenth-century understandings of landscape were largely shaped by the writings of Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant on the concept of “the sublime,” which was characterized as a sense of greatness infused with terror, made beautiful by the viewer’s perception of distance and safety. In an essay for Tate Papers no. 13, art historian Diana Donald aptly summarizes the aim of Church’s arctic masterpiece: “For Church, the Arctic is the sublime dwelling-place of God, into which humans venture at their peril.”

Ironically, it was during a search for Franklin’s lost expedition that the Northwest passage was finally discovered. In October of 1850, Captain Robert McClure spotted the passage from the top of a peak during an overland sled trip launched while his ship was, fittingly, trapped in the ice of a nearby bay. Unsurprisingly, like the Franklin men, McClure and his crew were trapped by sea ice for three years until their eventual rescue (although unlike the doomed Franklin Expedition, all but five crew members survived). The Northwest Passage was not successfully traversed for another 53 years.

William Bradford, Arctic Sunset, 1874. Image © Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence

As global warming has progressed, the arctic seas, a primary focus of arctic sublime painting, have undergone terrifying changes. The looming masses of Church’s icebergs that brought many expeditions to tragic ends have slowly melted into increasingly open seas. In recent years, the Northwest Passage has been easily passable in late summer. In 2009 the Beluga Foresight became the first commercial shipping vessel to cross the Northwest Passage. In an interview with the BBC, captain Valeriy Durov described the experience: “I was slightly surprised by what we saw… there was virtually no ice on most of the route. Twenty years ago, when I worked in the eastern part of the Arctic, I couldn’t even imagine something like this.”

In September of 2016, the Crystal Serenity became the first passenger cruise ship to traverse the Northwest passage, carrying over one thousand vacationers who paid between $22,000 and $120,000 to cruise the Arctic before it disappears.

–Megan O’Hearn, Education & Outreach Manager

Interested in more images of Arctic exploration? Take a look at Cornell University’s open-access collection Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland.