The women who shaped America, in photographs

Unknown; Young women holding a sign which reads, ‘Self Supporting Women.’ Several other women grouped near the banner are holding balls; 1914. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

March is Women’s History Month, and we’re celebrating women who shaped the political and social landscape of America with a tour of an expansive photographic archive documenting their experiences.

The Schlesinger History of Women in America collection contains 36,000 images from the archives of the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library at Harvard University. The Schlesinger Library’s collections encompass women’s rights and feminism, health and sexuality, work and family life, education and the professions, and culinary history and etiquette. It documents women’s experiences in America between the 1840s and 1990s and is sourced from donations made to the library, including the papers of many prominent female activists, politicians, and leaders. In making the stories of women’s lives available to all, the library combats assumptions that women’s roles have been tangential in the course of American history.

A fascinating characteristic of the Schlesinger archive is its blend of professional photographs, in the form of news and formal portrait photography, with vernacular photography. Vernacular photographs are images taken by non-professional photographers documenting the everyday: a new bicycle, parties, pets, family members, and more. Your phone, social media, and family albums are full of them. These images provide a window into the public and private lives of the women represented in the archive, their families, friends, homes, vacations, trips abroad, and more. In “Doing the Rest: The Uses of Photography in American Studies,” Marsha Peters and Bernard Mergen note “though each photograph records only one instant in an event, the cumulative body of these photographic moments can provide information about cultural values and attitudes as well as about the style and design of a society.” When we delve into personal snapshots, we can gain a sense of the individual through the visuals, ideas, and people that repeatedly surface in their images.

Let’s take a look at a few of the exceptional women represented in this collection:

Maud Wood Park

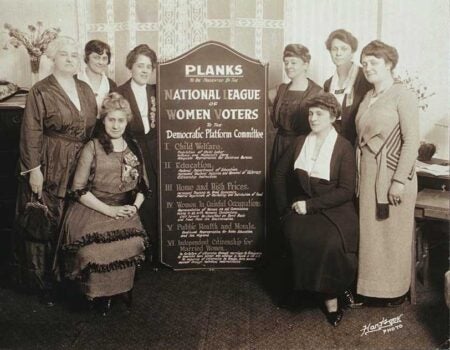

- Hartsook Photo; Group portrait of eight women holding a sign listing the planks to be presented by the NLWV to the Democratic Platform Committee; 1920. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

- J. E. & Co. Purdy; Four portraits of Maud Wood Park, wearing a white blouse; 1920. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

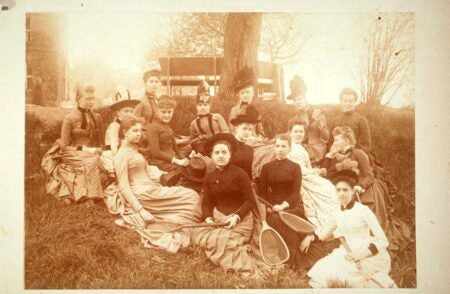

- Unknown; Fifteen young women seated on lawn, including Park; 1887. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

- Unknown; Aerial view of women, carrying banners and wearing light-colored shawls and caps, walking down a street, crowded on both sides by male and female onlookers. The first two banners read ‘Julia Ward Howe’ and ‘Harriet Beecher Stowe; 1913. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

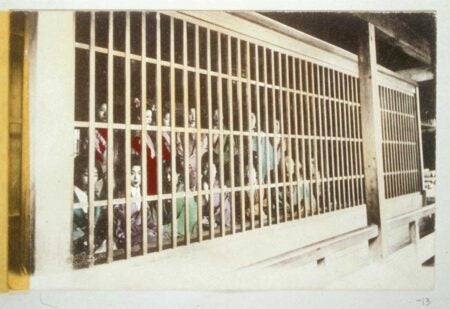

- Unknown; Prostitute house in Yoshiwara: many women, seated and standing behind a grid-like screen reminiscent of a jail cell; (circa 1909-1910). This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

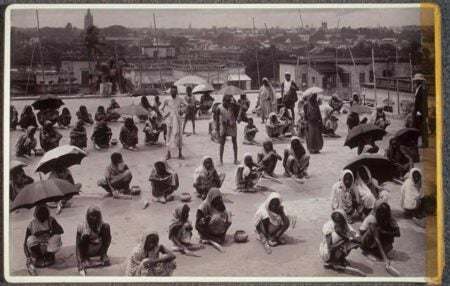

- Unknown; Male and female construction workers in Calcutta; (circa 1909-1910). This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

The Schlesinger archive originated from a donation of materials related to the Women’s Suffrage movement by Maud Wood Park, a graduate of Radcliffe College and the first president of the League of Women Voters when it was founded in 1920. Photographs of Park with friends and colleagues, news coverage of the 1913 Suffrage parade in Washington D.C., celebrations of the ratification of the 19th amendment, and snapshots from conventions for the League of Women Voters document the private lives and public battles of women demanding the right to vote in the early 20th century. Also included are Park’s own images from a trip around the globe taken between 1909 and 1910, many of which document the experiences of women outside the United States and Europe.

Edith Spurlock Sampson

The archive also includes photographs from the files of Edith Spurlock Sampson, a social worker, lawyer, and the first African-American woman to become a delegate of the United Nations. Spurlock became the first African-American woman to be elected as a judge in the United States, serving in Cook County, Illinois (the Chicago area) between 1962 and 1978. Spurlock’s photographs are delightful in their contrasts. In a striking 1951 image we look over Spurlock’s shoulder as she addresses an audience of white, male correspondents at a Vienna press conference captivated by her speech; in another, a cool and casual Spurlock, purse in hand, poses in front of the Sphinx on a breezy day.

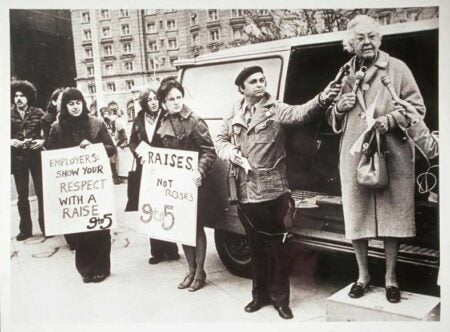

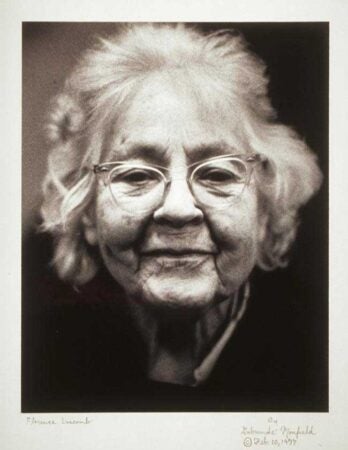

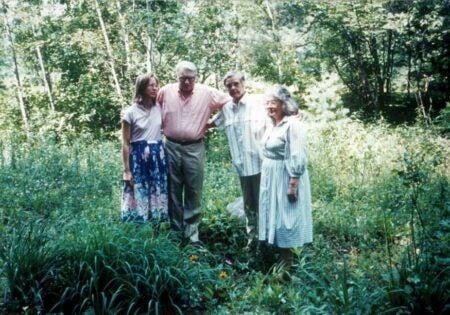

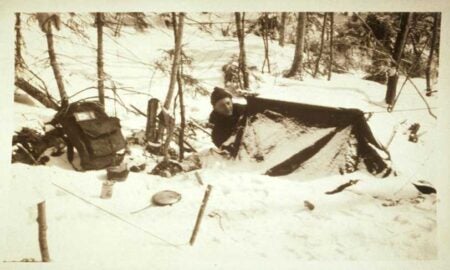

Florence Luscomb

- Boston Globe; Untitled [Florence Luscomb];1974. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Gabrundé Monfield; Untitled [Florence Luscomb] 1977. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Unknown; Untitled [Joy Harvey, Walter O’Brien, Louisa Howe, Barbara Brown-Massey at Florence Luscomb grave site.]; 1987. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Unknown; Untitled [Appalachian Mountain Club]; circa 1922-1934. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Florence Luscomb, a 1909 graduate of MIT’s school of Architecture, became involved in political and social activism in 1917 when she began working for the Boston Equal Suffrage Association. Luscomb eventually became a full-time activist, living off an inheritance and working for no pay to avoid taking jobs from those in need. After decades of activism she was embraced as a vital link between women’s movements past and present by second wave feminists, whom she encouraged to embrace the voices of black and poor women as part of the movement. In her photographs we see professional portraits and documentation of her activist work in the first and second waves of the feminist movement. We can also glean a sense of her love for the outdoors–her photographs show countless hiking and camping trips–and her closeness with friends and family through images of birthday celebrations and other gatherings, ending with a poignant image of loved ones lingering by her gravesite.

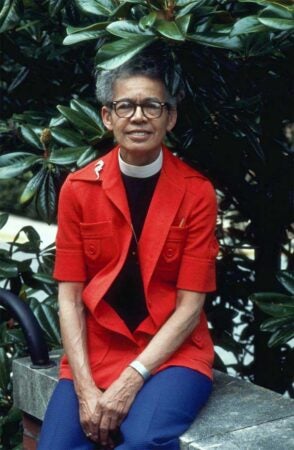

Pauli Murray

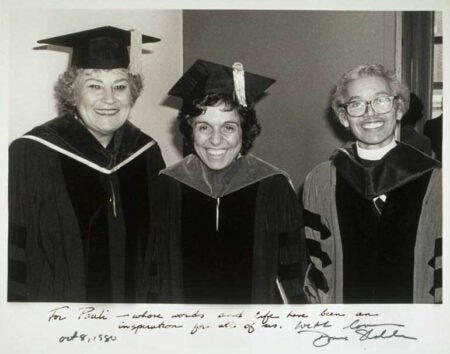

- Metropolitan Photo Service, Inc.; Bella Abzug, Donna E. Shalala, Pauli Murray; 1980. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

- Unknown; Pauli Murray graduation from Richmond Hill High School; 1927. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

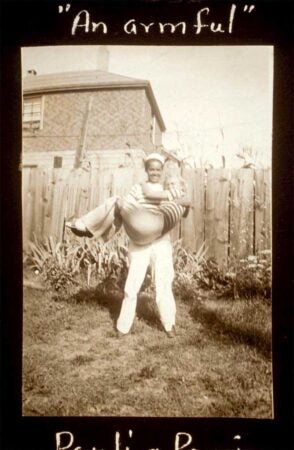

- Unknown; Pauli Murray carrying Peggie; 1937. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

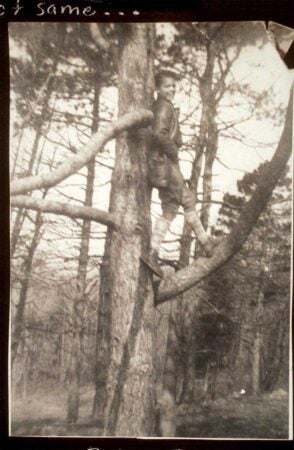

- Unknown; Pauli Murray standing in a tree; (circa 1928-1941). This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

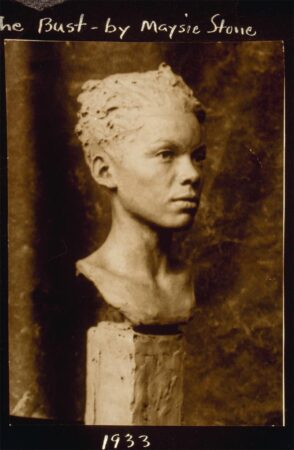

- Unknown; A bust of Pauli Murray; 1933. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

- Unknown; Untitled [Pauli Murray]; 1978. This image has been made available by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

Pauli Murray was a 1944 graduate of Howard University School of Law. Her thesis, “Should the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy Be Overruled?,” would later guide Thurgood Marshall’s strategy in the Brown vs. Board of Education case. Murray, who was openly queer, faced discrimination throughout her education. Her activism was at times complicated by her sexuality; after an arrest for refusing to move from a bus seat, she had difficulty obtaining legal representation because she was in a romantic relationship with her female travel partner. Murray became an activist against racial and gender discrimination, working for the ACLU, serving as a member of the Commission on the Status of Women, and co-founding the National Organization for Women. In 1977 she became the first African-American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest, a position which she held until her retirement. Her depth and energy are highlighted through the collection’s images that span through her teenage years, her 20s and 30s, and her later years in the priesthood.

Maud Wood Park, Edith Spurlock Sampson, Florence Luscomb, and Pauli Murray are just a few examples of exceptional women in America’s history. View images of other influential women by browsing the entire Schlesinger History of Women in America collection in the Artstor Digital Library.

Learn more about this collection and the women it represents on JSTOR:

Women Suffrage Collection at the Schlesinger Library, Harvard University:

Moseley, Eva. “Documenting the History of Women in America.” The American Archivist 36, no. 2 (1973): 215-22.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40291488

Maud Wood Park:

Strom, Sharon Hartman. “Leadership and Tactics in the American Woman Suffrage Movement: A New Perspective from Massachusetts.” The Journal of American History 62, no. 2 (1975): 296-315. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1903256

Edith Spurlock Sampson:

“Edith S. Sampson: APRIL 12, 1957, REGIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE LINKS, KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI.” In Women and the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1965, edited by Houck Davis W. and Dixon David E., 72-80. University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2tvf4t.12

Florence Luscomb:

Strom, Sharon Hartman. “Challenging “Woman’s Place”: Feminism, the Left, and Industrial Unionism in the 1930s.” Feminist Studies 9, no. 2 (1983): 359-86.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3177497

Pauli Murray:

Mack, Kenneth W. “The Trials of Pauli Murray.” In Representing the Race, 207-33. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press, 2012. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt24hhwm.13

Works cited:

Peters, Marsha, and Bernard Mergen. “”Doing the Rest”: The Uses of Photographs in American Studies.” American Quarterly 29, no. 3 (1977): 280-303.