Science and history converge in Cornell’s glacier photographs

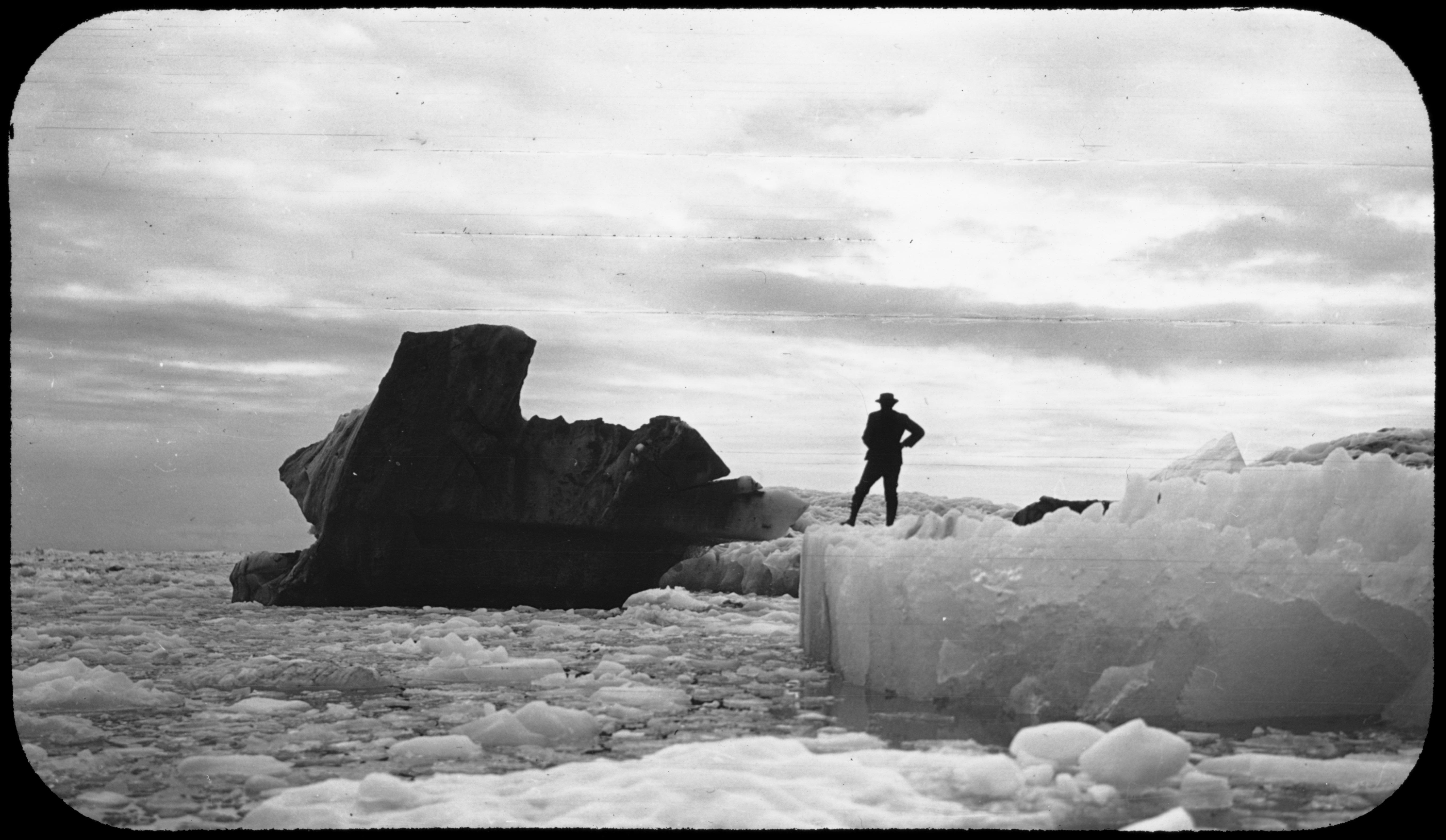

Black iceberg. 1909. Image provided by Cornell University.

Cornell: Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland archive is a magnificent photographic assemblage of Arctic expeditions undertaken by Cornell faculty in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The majority of photographs document sweeping views of glaciers, their boundaries, and coordinates. Others portray explorers crossing the Arctic terrain by boat, foot, sled, and train, revealing the human effort involved in traversing the Arctic for scientific purposes. These expeditions sought to research the development and behavior of glaciers from a scientific perspective during a period in history when public interest in the Arctic surged. Today, the images in this archive have become a locus for interdisciplinary research.

Artstor’s Megan O’Hearn sat down with Cornell faculty members Matthew Pritchard, associate professor of geophysics, and Aaron Sachs, associate professor of history, to learn about their collaborative approaches to understanding and illustrating the process and impact of global warming using this incredible archive.

Meg O’Hearn: Can you give us a quick history of Cornell’s Historic Glacial Images of Alaska and Greenland archive?

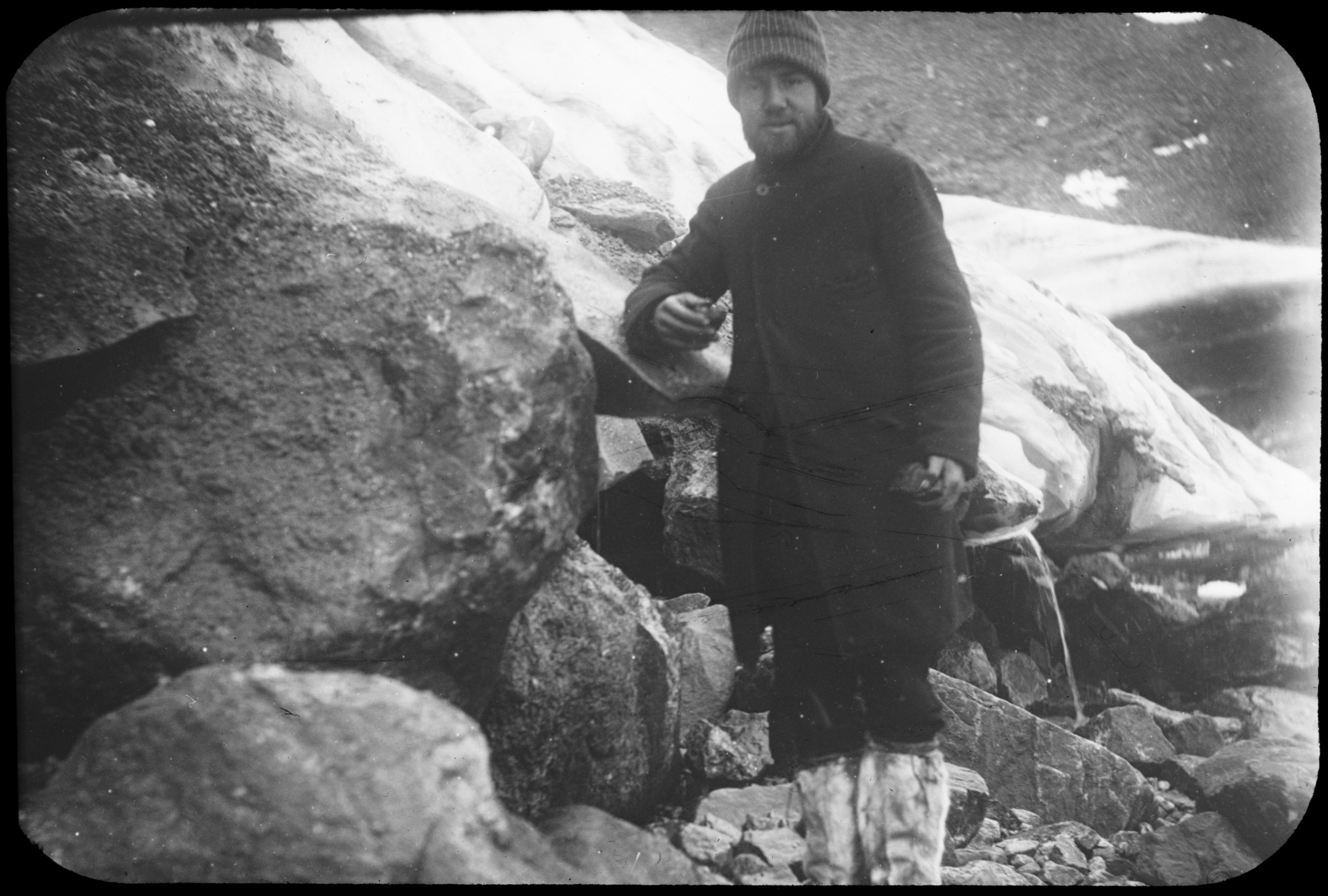

Matthew Pritchard: The photographs are part of the Cornell archives and are particularly related to two Cornell faculty members. One is Ralph Stockman Tarr, who became a faculty member starting in 1892, and the other is one of his students who eventually became a faculty member, Oscar Von Engeln. The collection is an assemblage from different expeditions made by various Cornell faculty and students between 1896 and 1911. All those photographs were in the archives with the rest of the documents from these two people, but we weren’t aware of them until an Emeritus faculty in our department was cleaning his office and brought us a box of glass plates that had not been included in that collection.

MO: Did Cornell invest a lot in expeditions such as these?

MP: As far as I know, to Greenland there was just this one big expedition that was in 1896, and then there were the ones to Alaska in 1905, 1906, 1909, and 1911, although smaller groups of Cornellians participated in other Arctic expeditions during this time. The National Geographic Society funded the last couple, early ones were partly funded by the US Geological Survey and a few other by the American Geographical Society and a hodgepodge of local benefactors here in Ithaca. It ended when Tarr had his untimely death in 1912.

MO: How did he die?

MP: He was 48, he was going to the field to see glaciers in motion and was starting to do some experiments using ice here locally and slowly deforming them to see how ice could move. They’d build a shed outside so he could do some experiments on how ice deforms in the winter. The story was it was a very cold March evening, and he got pneumonia and died a few days later.

MO: Amazing, to have made it through all those voyages and then…

MP: Some of his biographers say he was this person who lived his life in a hurry with a sword over his head. He was somebody who wanted to get things done.

Aaron Sachs: I can tell you more broadly in American culture this was a time when Arctic exploration had a great deal of prestige and cultural interest. It was the moment when this kind of exploration was switching from emphasizing scientific concerns to emphasizing more commercial–and you might even say masculine–concerns. This is the moment when people are getting excited about possibly making it to the North Pole, and lot of these expeditions were getting commodified and sensationalized in American culture. There was a huge range of goals from the strictly scientific ones to the broader ones like the ability to marvel and say, “look at what we’re able to, where we’re able to go!” and the sense of even gaining control over these extreme environments.

Boulder carried by Nugsuak Glacier. 1896. Greenland. Image provided by Cornell University.

MO: What led you to work with the collection?

MP: In some sense, it was driven by a need for finding a mechanism to fund the digitization. There was a special program for grants in the college of arts and sciences. At most universities, as a Geology professor I would be in the college of arts and sciences, but about 45 years ago, the geology department left that college and joined the college of engineering. We needed to find a collaborator in the college of arts and sciences. We contacted Aaron, based on his interest in historic images, and he was willing to work with us on this proposal and eventual project. That was sort of how we discovered each other.

MO: What was your approach to working with the collection?

MP: I think it’s an amazing benefit that we are approaching it from such different angles and that we’re interested in the same images for totally different reasons. Our look at the archive is very practical at this point; it’s still trying to understand what images we have, from what perspectives we have them, and trying to compare the metadata with more modern views of the same glaciers to try to understand how those glaciers have changed in the last over 100 years. That’s what brought us to the picture: what do we have, and where is it. I think Aaron was able to use images in a different way, which I think is fantastic.

AS: For me, I was grateful when Matt reached out. These images and all of the surrounding concerns were already things that I had been interested in for a long time. My first book was about scientific exploration and had a fair amount about the Arctic and I’ve always used visual images. I’m also very active on campus in interdisciplinary environmental studies, so that was another thing that was exciting about this: getting to work with people who are approaching these things from a completely different perspective but who share a strong interest in climate change. Once there are some present-day images comparing how those glaciers are now to how they were then there could be all kinds of additional publication opportunities that I could imagine being that much richer because they have the present day scientific angle, but then I could contribute more historical context. That idea of contextualization is one of the main things that I work on with my students in the classroom; they look at these images and we talk about the specific moment when they were created.

MO: You are also involved in a group across campus that seeks to look at environmental studies issues like global warming from the perspective of a number of different disciplines?

AS: It’s called CREST for short, and the acronym stands for the Cornell Roundtable on Environmental Studies topics. Environmental issues are so complicated that we’d all be better served if we talked about them together from our different disciplinary perspectives.

When CREST gets together, the idea is to discuss a topic that may have nothing to do with your research. You would show up to this conversation not because it could help you with your work, but because you recognize it as an issue that people are not going to be able to solve just by being an excellent historian or an excellent geologist. Next week we’re having some activists from the community come to campus to talk about a plan for carbon fees. They want to throw these ideas out and see how people might respond from the perspective of earth and atmospheric sciences as opposed to how people might respond from economics or political science, and try to put those perspectives together and see what the tensions are and where the constructive common ground might be.

MO: Matt, you’re conducting research on glacial change with these images by comparing them to remote sensing data. Can you explain your research process and what you are looking for in these photographs?

MP: Primarily, our task at this point is trying to get the metadata straight so that people can more easily access these pictures and figure out which glaciers we actually have pictures of and what the angle is so that we can get new images taken from the same perspective. That’s one of the key things: to try to get the coordinates of where the picture was taken from.

In a broader sense, my research is focused on trying to quantify how glaciers are changing. I remember my first conversation with Aaron about this. He was asking the very good question of well, we know the glaciers are diminishing in size, what more do we need to know, if I can paraphrase what he asked. We are trying to get a step beyond that because not every glacier is the same. Some are changing more rapidly than others. Most are retreating, a few are stable or advancing. What are the conditions that lead to that? That’s really the scientific motivation: to try to understand, over the course of decades, how glaciers respond to changing temperatures and changing precipitation patterns, and how these patterns are reflected spatially. We’re using remote sensing data, but remote sensing data only goes back a few decades. To really get a perspective that goes back a century or more we need to use other types of historical documents and records to try to understand the longer-term behavior.

Columbia Glacier from one of Curtis sites. 1909. Prince William Sound, Valdez-Cordova, Alaska. Image provided by Cornell University.

MO: What other documents are you looking at?

MP: I should say that our group is focused on this particular collection, but the community at large is focused on using images from other expeditions that happened in Alaska and Greenland. Our expeditions are just a small slice in that broader effort. I was just at a conference on the Arctic where they have compiled records from whaling ships and a variety of other expeditions throughout the 18th and 19th century to try to understand what was the distribution of sea ice in the Arctic in order to understand whether the current changes we’re seeing here are extreme within this historic record. In a lot of this, the key question is to what extent are the changes we’re seeing now forced by human activities and to what extent is there natural variability. With only a record of a few decades, it’s hard to constrain what is that natural variability. That’s why historical documents are important to better understand how nature varies the climate depending on all the different components of the system.

MO: Did you find any unexpected parallels in your work?

MP: I would say that I’ve learned a lot by listening to Aaron talk about the collection, it’s very interesting to hear how he approaches things in a different way. My focus is very practical, trying to understand, geographically, where these pictures are and do we have the metadata correct, and how do we compare that with existing images. And we gain some understanding of why the expeditions took place by putting them in the context of what else was happening in the arctic and culturally at the same time.

AS: For me, it’s exciting to connect with people like Matt who are doing cutting edge scientific work that helps us make broader arguments in culture and in politics about the significance of melting glaciers. Thinking ahead to when there may be present day images that we can actually compare, it’s exciting to consider possible publications that would take this rich, broad approach of presenting science, culture, and history simultaneously. Matt has been emphasizing the practicality of his approach but I should say I’ve seen him present a few times about this and from my perspective, it’s also great that he and the other people he’s been working with have a taken a strong interest in the people who were involved in these expeditions as people. There are other things in the archives like field notes that shed light on this whole enterprise and help us tell this as a human story as well as a scientific story.

I feel like that sort of approach is really something we need in our present-day circumstances. There’s an awful lot of science out there that has failed to connect with people, in my opinion, because it hasn’t taken enough of a cultural approach. That’s part of the promise I see here.

MP: To follow up on what Aaron said, it’s interesting to think about how science was done 100 years ago, which is very different than the type of milieu that we’re in now, in terms of how funding is done, the scale of the scientific problems we attack. I don’t want to romanticize what the “old school” people did, but it’s important to appreciate the difficulties and the personal sacrifices they made, as well as their creativity. They didn’t just put down the scientific data that they collected. They were taking pictures of glaciers, then putting some sort of known human structure next to it to give a sense of scale, to help viewers understand the vastness of what they are looking at. And so they would put pictures of the Bunker Hill Monument or other buildings that were famous at the time to help the general public appreciate what they were looking at.

I feel inspired by that example to try to do the same, to relay an appreciation for what these people did in addition to the scientific data that they collected.

You may also be interested in Frederic Edwin Church’s The Icebergs and the tragedy of the Arctic Sublime