Fake news: the drowning of Hippolyte Bayard

- Hippolyte Bayard, Self Portrait as a Drowned Man, 1840. Data from University of California, San Diego.

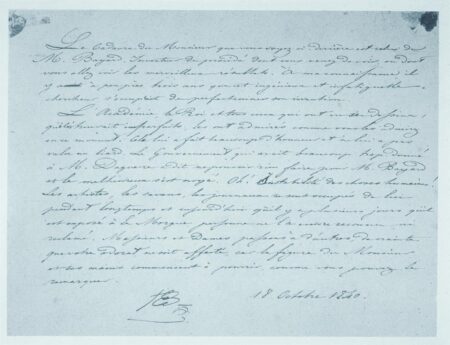

- Hippolyte Bayard, Self Portrait as a Drowned Man (verso), 1840. Data from University of California, San Diego.

In a grainy 1840 photograph, a partially-covered corpse is propped against a wall, its decay evident in the darkening skin of the face and hands. The body is that of Hippolyte Bayard, an early inventor of photographic processes and supposed drowning victim, and written on the image verso is a strange note:

The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you, or the wonderful results of which you will soon see. As far as I know, this inventive and indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with the perfection of his discovery. The Academy, the King, and all those who have seen his pictures admired them as you do at this very moment, although he himself considers them still imperfect. This has brought him much honor but not a single sou. The government, which has supported M. Daguerre more than is necessary, declared itself unable to do anything for M. Bayard, and the unhappy man threw himself into the water in despair. Oh, human fickleness! For a long time, artists, scientists, and the press took interest in him, but now that he has been lying in the morgue for days, no-one has recognized him or claimed him! Ladies and gentlemen, let’s talk of something else so that your sense of smell is not upset, for as you have probably noticed, the face and hands have already started to decompose.

The note is signed by none other than the drowned man himself: “H.B. 18 October, 1840.”

Bayard’s image is the first known instance of a faked photograph and was taken just one year after what can be considered photography’s official “start” date in 1839. He staged the image in protest of the lack of recognition he had received for his contributions to the invention of the medium of photography–credit that went instead to the now-famed inventor Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre.

As the first known example of a faked photograph, this image illustrates two qualities of photographs: first, that they can depict the world in a manner that closely mimics the way we see it. Second, that since their invention, they have been staged or altered in ways that remain consistent with the way we see. This consistency makes them all the more believable.

These contradictions persist today, and are heightened by the ubiquity of digital photography. While photography remains one of our principal forms of evidence, we are well aware of the existence of software like Photoshop–unlike early viewers of photography, who had more limited knowledge of tricks of the camera and printing process.

–Meg O’Hearn, Education & Outreach Manager