The strange fates of pillaged mummies

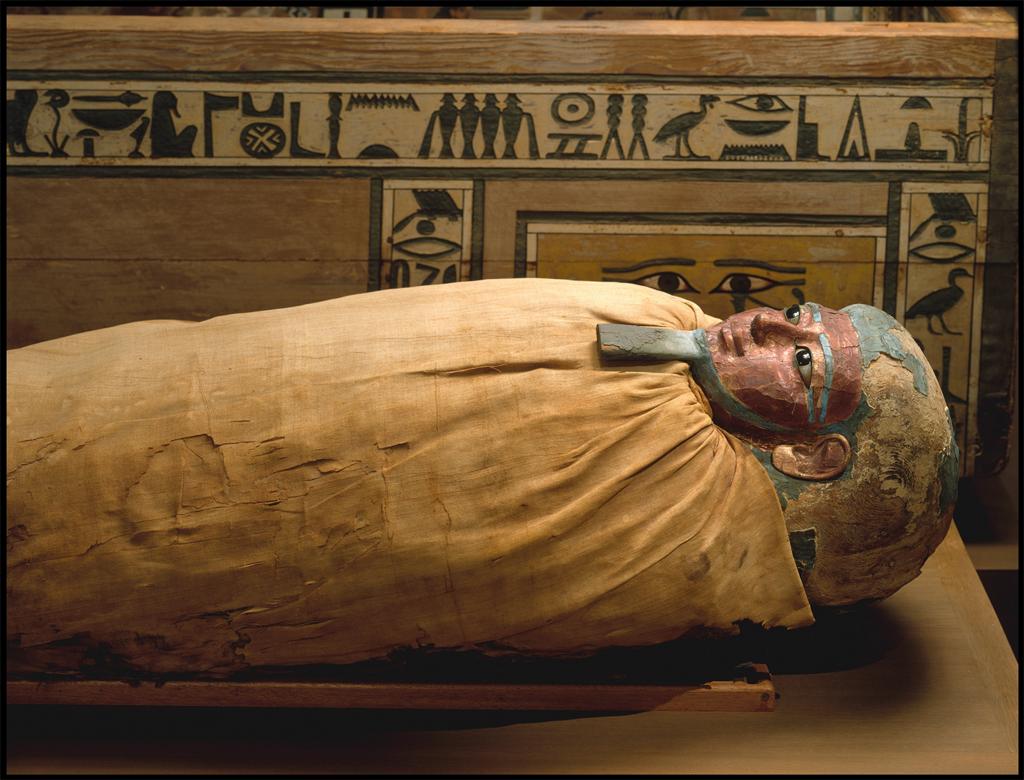

Mummy of Ukhhotep, Egypt. Detail. c.1981-1802 B.C.E. Wood, cartonnage, paint, linen, human remains, obsidian, gold, alabaster. Image and data provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In an 1898 article for Scientific American, a chemist describes his process for working with a powdered material that smelled of myrrh and meat extract:

On heating the powder turns dark brown black, with a pleasant, resin-like odor of incense and myrrh, then throws out vapors with an odor of asphaltum; it leaves a black glossy coal which leaves behind when burnt 17 percent of ash with a strongly alkaline reaction, evolving plenty of carbonic acid when sprinkled with acids. In the closed tube vapors of acid reaction are obtained. With hot water a yellow brown solution of neutral reaction is obtained which smells like glue and extract of meat when inspissated…”

The powder in question was in fact the ground desiccated corpse of an ancient Egyptian, heated for the purpose of creating commercially-produced oil paint. Shocked? Let us treat you to a short history of the many strange fates of pillaged mummies between the sixteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Philips Galle, after Maerten van Heemskerck. The Pyramids of Egypt (from The Eight Wonders of the Ancient World). c. 1572. Engraving. Image and data provided by The Illustrated Bartsch.

Although interest in ancient Egyptian culture would peak in the nineteenth century, its early roots can be traced back to the Renaissance, when scholars rediscovered Classical accounts of the civilization. The limited available knowledge led to some unfounded beliefs. In “Egypt and Egyptian Antiquities in the Renaissance,” Karl H. Dannenfeldt describes the travel memoirs of Spanish historian Pedro Tafur, who upon visiting the pyramids postulated that “beasts of burden went up these ‘granaries of Joseph’ and unloaded the grain through ‘windows and so they fill the granaries to the top.’”

Incomplete knowledge also led to a misunderstanding of mummies. Bitumen, a naturally occurring black resinous material, was used in Middle Eastern medicine for centuries prior and was sold under the Persian name mummia or mumiya. Because of the similarities in nomenclature and visual characteristics between bitumen and mummy–the blackened flesh of mummies resembled bitumen, and bitumen was documented as one of several ingredients sometimes used in the mummification process–the medieval European translation of the word mummia erroneously came to include both bitumen and the flesh of mummies. They became interchangeable forms of medicine, believed both to cure a diverse set of ailments from internal bleeding to hiccups.

Mummy was widely stocked in European apothecaries where it could be purchased in several forms, including powdered and chopped preparations. The high demand for raw materials led to gruesome creativity on the part of unscrupulous mummy dealers, who began creating fakes by embalming and drying the stolen corpses of recently deceased slaves and criminals, and selling them to unwitting buyers. The dead were selected without regard for cause of death, and it is possible this practice may have helped spread the plague.

Not everyone believed in the healing powers of powdered mummy, however. Dannenfeldt describes one sixteenth century doctor who condemned its use due in part to foul side effects, which included “the paine of the heart or stomacke, vomiting, and stinke of the mouth.”

Meanwhile, the versatile mummy became a popular material for another application: paint pigment. Painters commonly applied mummy brown, a sheer black-brown wash, to their canvases between the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries. The paint’s composition varied greatly and conservationists have struggled to identify specific examples of its use through chemical testing. It is said Martin Drolling used large quantities in Interior of a Kitchen (1815). Eugene Delacroix documented adding the grisly color to his palette sometime between 1824 and 1854, and it may have been used in painting Liberty Leading the People (1830). The pigment was also believed to be popular with the Pre-Raphaelite painters–although not all were aware of its origins. Upon discovering his tube of mummy brown contained human remains, painter Edward Burne-Jones requested his nephew Rudyard Kipling help him give it a proper burial.

As the field of Egyptology–and the rise of Orientalism–grew during the early nineteenth century, interest in mummies began to spread. Their appeal was broad: not only did museums collect them, but travelers in search of exotic souvenirs for display in their homes purchased them in markets, or paid to take part in staged expeditions where they stumbled upon caches of pre-pillaged mummies placed conveniently for discovery.

Linen mark, Wah. ca. 1981-1975 B.C. Image and data courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The truly curious could further explore the intrigue of mummies at unwrapping parties. One such event was held in 1833 by surgeon and antiquarian Thomas Pettigrew at Charing Cross Hospital, and attracted a prestigious crowd of fellow doctors, archaeologists, and the British Museum’s keeper of antiquities. Not all such parties were held for researchers, however. The general public could purchase tickets to dramatized unwrapping performances held in theaters, after which the discarded cloth wrappings served as take-home favors.

Today we treat mummies with a bit more reverence, focusing on their history and culture rather than their eerie appearances. But our strange relationship with mummies from centuries past still surfaces occasionally: two pigment shops noted they had mummy parts in storage as late as 1964 and 1980, and in 1999 the Head of Corporate History for Merck Pharmaceuticals was surprised to find long-forgotten medicinal mummy parts in storage.

–Megan O’Hearn, Education & Outreach Manager

Sources:

“Miscellaneous Notes and Receipts.” Scientific American 78, no. 17 (1898): 266. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26118483

Dannenfeldt, Karl H. “Egypt and Egyptian Antiquities in the Renaissance.” Studies in the Renaissance 6 (1959): 7-27. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2857179

Rogers, Beverley. “UNWRAPPING THE PAST: EGYPTIAN MUMMIES ON SHOW.” In Popular Exhibitions, Science and Showmanship, 1840-1910, edited by Kember Joe, Plunkett John, and Sullivan Jill A., 199-218. Pittsburgh, Pa: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1djmj49.17.

Languri, Georgiana M., and Jaap J. Boon. “Between Myth and Reality: Mummy Pigment from the Hafkenscheid Collection.” Studies in Conservation 50, no. 3 (2005): 161-78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25487742

Dannenfeldt, Karl H. “Egyptian Mumia: The Sixteenth Century Experience and Debate.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 16, no. 2 (1985): -16380.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2540910