The curious case of collector Hearst: new selections now available from the William Randolph Hearst Archive

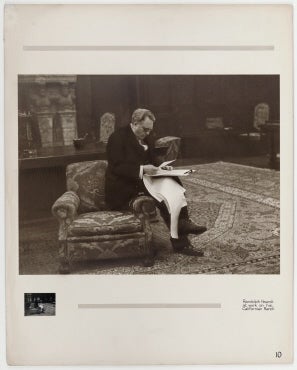

Erich Salomon. The American newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst reading telegraphs in his castle “La Cuesta Encantada,” San Simeon, CA. 1930. Silver gelatin photograph. Licensed under CC0

The William Randolph Hearst Archive has contributed a collection of 2,050 images to Artstor, providing an intriguing perspective on the collecting passions of Hearst, the man best known to us as a newspaper baron, and notoriously immortalized on film as the unscrupulous “Citizen Kane.”

William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), shown above in an unusually pensive portrait, was an obsessive collector of art and all sorts of objects. His mother reported that he exhibited a “mania for antiquities” even as a boy. In the early ’20s, he acquired a five-story warehouse in the Bronx to store his holdings—even his six residences, including the castles of Saint Donat in Wales and the lavish estate in San Simeon, California, could not contain his treasures. By 1935, his collections were valued at more than $20 million. During the late ’30s through the early ’40s, when he neared bankruptcy, half of his art holdings were sold.

François Boucher. Venus and Mercury Instructing Cupid. 1738. Oil on canvas. Image and data provided by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Archive provides a full inventory of the warehouse with cataloged photographs of each acquisition—a dizzying, eclectic, and sometimes eccentric selection of varied antiquities, tapestries, armor, and every type of decorative art and ritual object imaginable from reliquaries to spinning wheels—even, allegedly, George Washington’s snuff box and a tea caddy that belonged to Thomas Jefferson. The Archive also reveals that Hearst partook of the more mainstream taste for European paintings and sculptures, populating his collection with artists favored by his contemporaries—Boucher (shown above), Canova, Copley, van Dyck, Fragonard, Gérôme, Reynolds, Sansovino, Vouet, and others. Many museums feature objects and works bearing his provenance: dozens of Greek vases at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; armor at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; silver at Colonial Williamsburg; diverse works at the Detroit Institute of Arts; and, most memorably, more than 900 items that he donated to form the core of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Over the past decade, Heart’s profile and importance as a collector have been expounded by an exhibition at LACMA: Hearst the Collector, and articles by Catherine Larkin.1

- German. Lusterweibschen or Weib-Lustre (chandelier). Wood, iron. Image and data provided by the William Randolph Hearst Archive, B. Davis Schwartz Memorial Library, LIU Post

- English. Georgian Cut Glass Chandelier. c. 1800. Image and data provided by the William Randolph Hearst Archive, B. Davis Schwartz Memorial Library, LIU Post

Delving into the Archive in Artstor, which features a selection of the full inventory, is an aesthetic odyssey. The extraordinary mingles with the mainstream and one comes to expect the unexpected. Consider the juxtaposition of two of the many chandeliers purchased by Hearst, one a cut-glass Georgian beauty with a prestigious provenance going back to Devonshire House in London—the epitome of crystal elegance—the other a German Lusterweibchen (little chandelier woman), a type of hanging lamp that dates back to the middle ages and is a hybrid of a carved female figure, candle holders, and, typically, antlers—one of several owned by Hearst.

- Egyptian, XXVI Dynasty. Hathor. Bas relief in limestone. 664-525 BCE. Image and data provided by the William Randolph Hearst Archive, B. Davis Schwartz Memorial Library, LIU Post

- Christopher Haines. Chased and Pierced Irish Silver Potato Ring. 1775. Image and data provided by the William Randolph Hearst Archive, B. Davis Schwartz Memorial Library, LIU Post

The sweeping reach of Hearst’s taste is gleaned through the pairing of unlikely finds — an ancient Egyptian stone relief of the goddess Hathor and a finely chased silver dish ring from Ireland, 1775, a stand used to protect table surfaces (sometimes anachronistically called a potato ring).

- Nuremberg, Germany. Silver Gilt Ship Model. 17th Century. Image and data provided by the William Randolph Hearst Archive, B. Davis Schwartz Memorial Library, LIU Post

- Augsburg, Germany, possibly Melchior Bayer. A Parcel Gilt Silver Figure of a Bear. c. 1625. Image and data provided by the William Randolph Hearst Archive, B. Davis Schwartz Memorial Library, LIU Post

- Jorg Ullrich. Parcel-Gilt Cup and Cover. c. 1540. Image and data provided by the William Randolph Hearst Archive, B. Davis Schwartz Memorial Library, LIU Post

In spite of the encyclopedic range of Hearst’s collection, the Archive reveals some pervasive preferences, notably a preponderance of German gold and silver work. One of Hearst’s estates, Wyntoon, featured Teutonic architecture—perhaps some of these objects were chosen for that setting. Three items provide a sampling of Hearst’s predilection: a silver gilt ship model from Nuremberg, 17th century, a parcel gilt bear, c. 1625, and a silver gilt covered cup, c. 1540.

In 1975, the entire collection of the William Randolph Hearst Archive, consisting of 125 original albums (currently rehoused as 160) documenting his inventory, as well as art sales catalogues, and other materials, was given by the Hearst estate to Long Island University with the stipulation that they would not be sold. A recent reappraisal of the Archive sheds light on the Gilded Age which Hearst personified, his politics, and most remarkably, his singular approach to collecting. The current contribution from the Archive to the Artstor Digital Library was supported by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

–Nancy Minty, Collections Editor

1 Catalog by Mary Levkoff, Hearst the Collector, NY, Abrams, 2008. Larkin is Associate Professor Long Island University, C. W. Post Campus: Catherine Larkin (2009) A Reappraisal of the William Randolph Hearst Archive at Long Island University: Information, Preservation, and Access, Visual Resources, 25:3, 239-257, DOI: 10.1080/01973760903122398, and Catherine Larkin (2013) The William Randolph Hearst Archive: An Emerging Opportunity for Digital Art. Research and Scholarship.