The art of plenty: In praise of still life painting

Bartolomeo Bimbi. Pears. 1699. Oil on canvas. Villa Medicea. Image and data provided by SCALA, Florence/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

Every year the subject of food rises in our thoughts and comes into greater and more glorious focus as we are swept up in a wave of planning, preparation, and consumption for the holidays. In anticipation and celebration of our sumptuous banquets and stolen treats, Artstor offers a feast of foodie still lifes. Think of this selection as an appetizer: with heaping mounds of fruit, Bartolomeo Bimbi’s monumental Pears (1699) heralds the abundant extreme of the genre.

First, let’s acknowledge that the term still life is, in fact, an oxymoron, based on the Dutch stilleven – stilled life (in the academic sense of life as in nature – all traditional works being naer het leven meaning after or from nature). Coined in the seventeenth century, the label was adapted in French, nature morte, and Italian, natura morta, literally dead nature, compounding the contradiction.

Giovanna Garzoni. Still Life with Bowl of Citrons. Late 1640’s. Tempera on vellum. Image and data provided by the J. Paul Getty Museum.

From the ancients through to the Impressionists, still life artists have prized naturalism, even to the point of illusionism. Pliny’s famous invocation of Zeuxis rendering grapes so real that the birds plucked at them has permeated the genre since Roman times. During the seventeenth century, at the court of the Medici in Florence, where Bimbi was commissioned to decorate entire rooms in fruits and vegetables, his colleague Giovanna Garzoni stippled a delicate rendering in tempera on vellum — Still Life with a Bowl of Citrons (late 1640s) — so fine that one senses the lone wasp traversing the knobby surface of the fruit. Regardless of scale, through studios across Europe, the goals of scientific observation and technical finesse were married in the quest for realism.

Francisco de Zurbarán. Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Rose. 1633. Oil on canvas. Image and data provided by the Norton Simon Museum.

In Spain, Francisco de Zurbarán and others developed their own variant known as bodegones (after the word tavern) which distilled the subject while lending dramatic, even mystical light, as shown here in the Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Rose (1633).

Jan Davidsz. de Heem. Still Life with Fruit and Lobster. 17th century. Oil on canvas. Photographer: Jörg P. Anders. Image and data provided by Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

The genre reached a fever pitch in the Netherlands during the prosperity and excesses of the Golden Age with the innovation of the pronkstilleven (pronk, meaning show or display), here illustrated by Jan Davidsz de Heem’s Still Life with Fruit and Lobster (17th century). On a canvas measuring nearly 3 by 4 feet the artist has laid a dazzling spectacle: a pyramid of luscious fruits and a livid lobster, crowned by glistening glassware and lustrous shells. At the upper corner, the sheen of a drawn curtain — another reference to Pliny who tells not just of Zeuxis’ grapes, but of a curtain painted by his rival Parrhasius so deceptively that it outfoxed Zeuxis who attempted to pull it aside. The painting and its pronk type invoke the vivid description of English Ambassador William Temple of his posting in the Dutch Republic: “The warehouse of the world, the seat of opulence, the rendez-vous of riches.”

Lest the viewer fall prey to the seductions of such a painting, it holds plenty of admonitions: beneath their soft blush, the grapes rot, and the lobster, so ubiquitous in these works, was a symbol of inconstance and instability in contemporary literature — characterized by its wayward movements backwards, forwards, and sideways (for more contemporary takes on the lobster, see Salvador Dali and Andy Warhol).

- Adriaen Coorte. Still Life with Asparagus. 1697. Oil on paper on canvas. Image and data provided by the Rijksmuseum. Public domain (CC0 1.0).

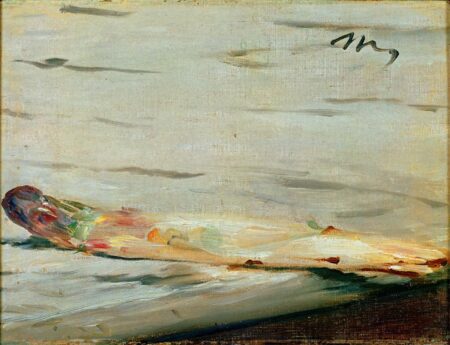

- Edouard Manet. The Asparagus. 1880. Oil on canvas. Musée d’Orsay. Image and data provided by Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives, ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

From the many Dutch painters of the era, the singular figure of Adriaen Coorte emerged around the end of the century. His answer to the genre: diminutive, darkened compositions with single subjects, like Still Life with Asparagus (1697) a tiny, glowing tribute to the vegetable. The painting, about life-size, is characteristically rendered in oil on paper laid on canvas, in invisible brush strokes. White asparagus, then known as white gold, was prized (and still is) since its stalks had to be covered during cultivation to prevent photosynthesis. If Coorte’s painting is an ode to asparagus, Edouard Manet’s single stalk, The Asparagus (1880) is its very essence.

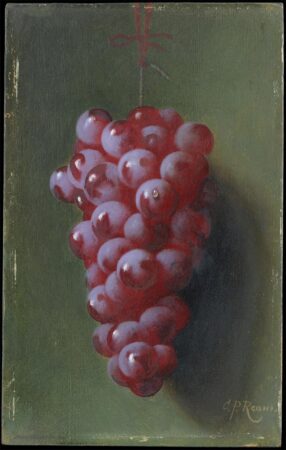

- Carducius Plantagenet Ream. Still Life with Grapes. c. 1850-1917. Oil on canvas. Image and data provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

- William Merritt Chase. Still Life: Fish. 1908. Oil on canvas. Image and data provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

- American, unknown. Trompe l’oeil fish in pressed glass. c. 1870. Pressed glass, paint, wood, velvet. Image and data provided by The Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The little known but regally named American painter Carducius Plantagenet Ream produced a fully Zuexian Still Life with Grapes in the later ninteenth century. All blush and no blemish, the fruit is animated by an immaculate water drop that embellishes the perfect illusion. Like Ream, New World painters sought the naturalism of the earlier European schools, a fact borne out also in the still lifes of William Merritt Chase, who had a particular skill for portraying fish. Chase’s Still Life: Fish (by 1908) epitomizes the concept of freshly caught. In the words of critic and collector Leo Stein: “Chase seems to take a saturated satisfaction in the swell and swing of the thick soft-bodied fish.” The illusion culminates in Trompe L’oeil Fish in Pressed Glass (c. 1870) an anonymous work that brilliantly crafts fishiness from pressed glass, paint, wood, and velvet.

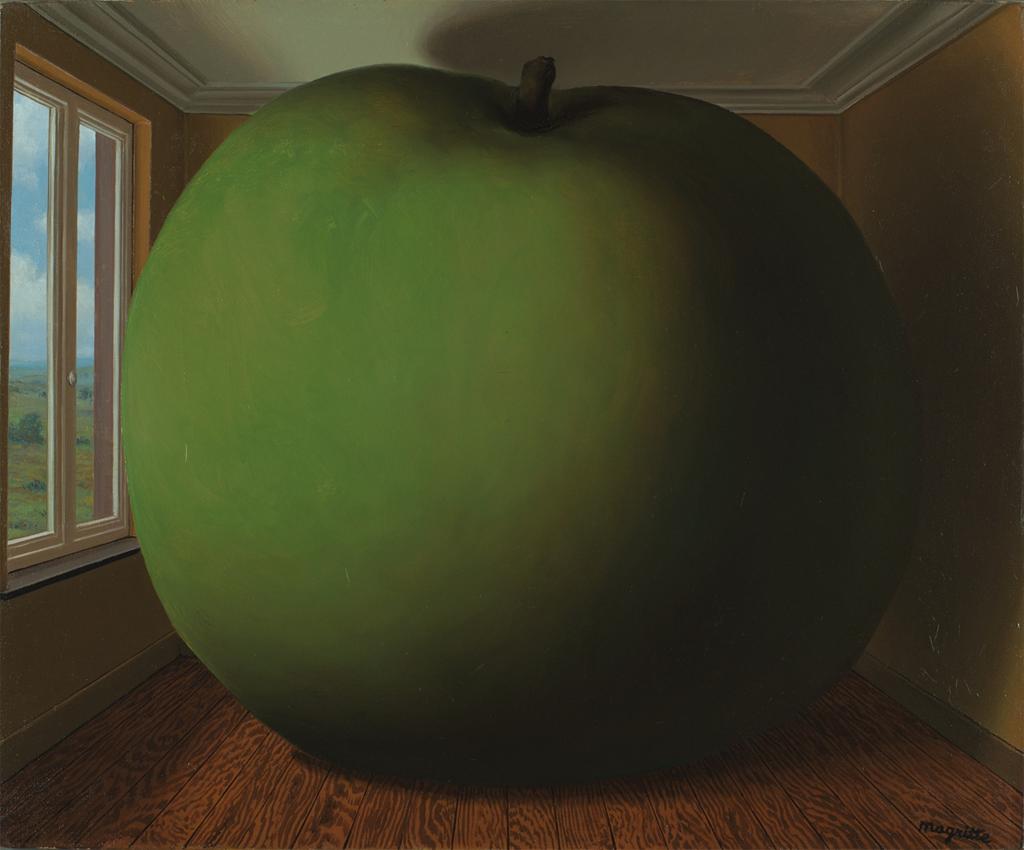

René Magritte. The Listening Room (La chambre d’écoute). 1952. Oil on canvas. Image and data provided by The Menil Collection, Houston. © 2018 C. Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Leave it to the magician and trickster surrealist René Magritte to ply his illusory powers in an exercise in ambiguity. In The Listening Room (1952) he has rendered the perfect apple. It is the very essence of appleness and yet not. The scale is impossible: How could this sensational fruit dominate a room (or is the room just tiny)? Typically, the artist provides only the hint of an answer. The apple that literally floats through his work, sometimes to obscure a face, is a common motif. He states “Those of my pictures that show very familiar objects, an apple… pose questions.” Perhaps less equivocal is the artist’s painted response, a work from 1964: a canvas with an immaculate depiction of the fruit and a familiar inscription — “Ceci n’est pas une pomme (This is not an apple).”

-Nancy Minty, Collections Editor