Pioneers of the deep: early Americans fathom the ocean

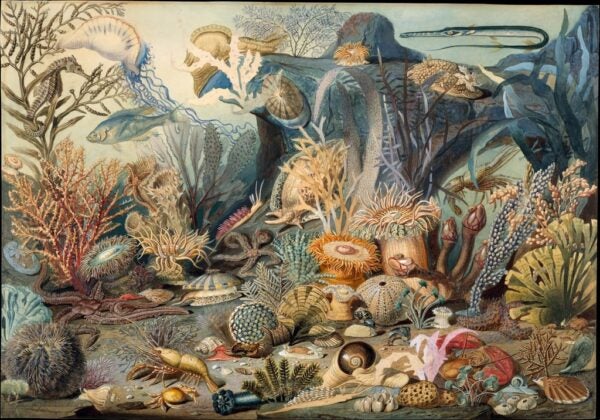

James M. Sommerville, Christian Schussele. Ocean Life. c. 1859. Image and data provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain.

More than 2 million of the images in Artstor are now discoverable alongside JSTOR’s vast scholarly content, providing you with primary sources and vital critical and historical background on one platform. This blog post is one of a series demonstrating how the two resources complement each other, providing a richer, deeper research experience in all disciplines.

During the mid-nineteenth century, the Atlantic presented a new, rich, and formidable frontier to American innovators who were laying the cables for the first transcontinental telegraph, to scientists capturing their first glimpses of aquatic life forms, and to artists exploring the hitherto unseen landscapes of the deep.

In 1855, the American naval officer Matthew Fontaine Maury published The Physical Geography of the Sea, a groundbreaking study of oceanography. The title “physical geography” reflects the fact that the term oceanography was not even in use at the time (first known as oceanology, the label for the autonomous science was coined during the scientific expeditions of the HMS Challenger of the Royal Society during the 1870s). In Maury’s introduction, he describes the promise of the new frontier: “The sea, from having long been an object of poetry and terror, may yet become a pathway of glory for scientific discovery, and may become as fruitful to men’s wants as dry land.” [1]

Maury’s vision was brilliantly fulfilled just a few years later in Ocean Life, a succinct but vividly illustrated pamphlet published by the Philadelphia physician James M. Sommerville in 1859. The single illustration for the publication is a lithograph based on the outstanding watercolor attributed to Sommerville and Christian Schussele where a supercharged section of the seafloor displays 75 different species (described in the accompanying text) from various geographical zones in full and glorious detail. Schussele was a professor of drawing and painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and Sommerville, the author, was a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences. The watercolor combines the precision of scientific observation in the depiction of its parts showing each pristine element to its best advantage, with the artistic tendency to delineate a carefully orchestrated composition, as in still life paintings. The author describes the contrived nature of the view in his introduction where he also reveals that he observed the sea floor through clear waters from a boat: “The grouping may be considered, rather as an intellectual truth than as a literal view. — It might be termed a mental oasis of the sea. — And it should be remembered that the floor of the ocean is not every where [sic] adorned with such forms of beauty.”

Edward Moran. The Valley in the Sea. 1862. Image and data provided by the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields.

It comes as no surprise that Sommerville was the owner (and perhaps commissioned) the extraordinary submarine landscape by Edward Moran, Valley in the Sea, 1862, arguably the first painting of its kind in America. The luminous and monumental work, nearly six feet long, idealizes the underwater valley much as Moran’s terrestrial landscapes and those of his Hudson valley colleagues, including his brother Thomas, outsized the local topography. While an illusion of realism is conveyed by passages of magnified naturalistic detail and highlight accents, the eye is deceived by skilled painterly persuasion. No less an authority than Jacques Cousteau confirmed this: “…It is a work of imagination, based on serious documentation. The artistic effect is strikingly pleasant although such scenery is totally unrealistic for two reasons: a) water transparency would never allow such distant visibility b) the warm colors of the anemones on the bottom would never be seen without artificial illumination.” [3]

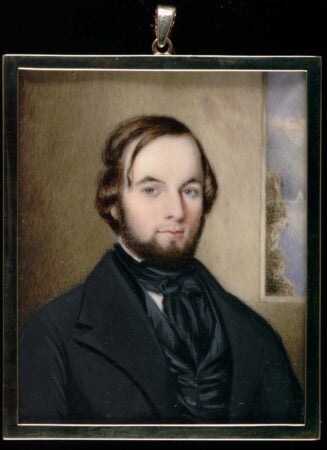

- Peregrine F. Cooper. Matthew Fontaine Maury. c. 1840. Image and data provided by the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

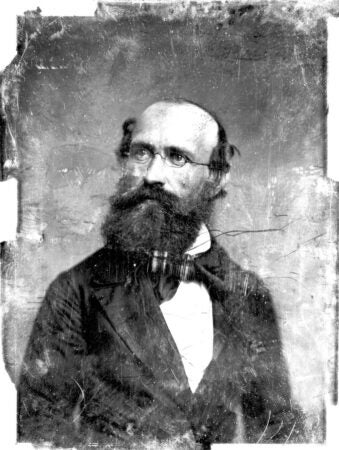

- Mathew Brady Studio. Cyrus W. Field. c. 1844-1860. Image and data provided by the Library of Congress.

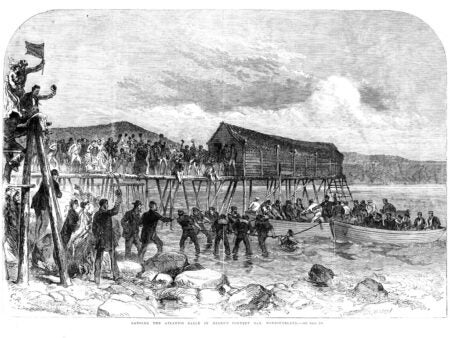

- Landing the Atlantic cable in Heart’s Content Bay, Newfoundland. From the London Illustrated News, September 8, 1866. Image and data provided by the Library of Congress.

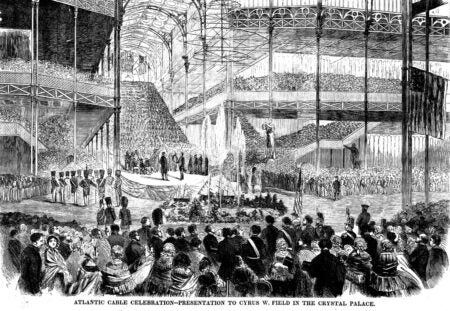

- Atlantic Cable Celebration. From Harper’s Weekly, September 11, 1858. Image and data provided by the Library of Congress.

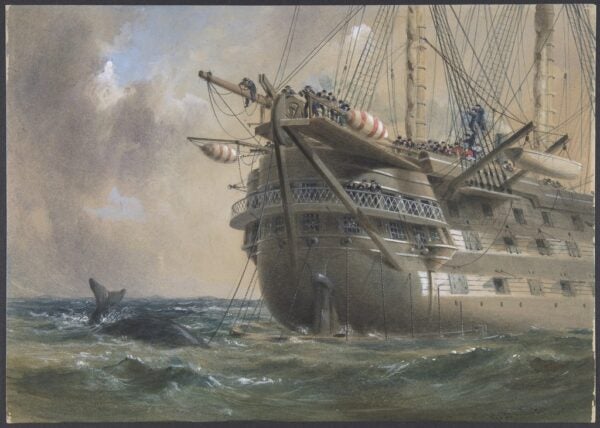

The accomplishments of Maury, Sommerville, and Moran resonate in the context of the technological breakthrough of the laying of the Atlantic telegraph cable. Telegraphic communications had already been established on land prior to the prolonged initiative to establish a transatlantic cable led by the tireless New Yorker Cyrus West Field. The initial successful attempt culminated in the dispatch of the first transatlantic telegraph in 1858 — a message from Queen Victoria to President James Buchanan that took 16 hours to transmit, glacial by our standards but much swifter than the traditional 10-12 days of steamer mail. A watercolor by Robert Charles Dudley depicts a stormy moment as a whale breaches the stern of the cable ship — H.M.S. Agamemnon Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable in 1858: a Whale Crosses the Line, 1865-1866. Here the old world meets the new as a refitted British battleship, resembling an antiquated galleon, sets the stage for modern communication. The telegraph was deemed the “eighth wonder of the world,” and celebrated on both sides of the Atlantic. In a print from Harper’s Weekly, we see Field honored at the Crystal Palace, London. Nonetheless mere weeks after the breakthrough the system failed and it was not until 1866, under Field’s unflagging leadership that it was resecured. A US/British alliance including the navies, financial partners, and governments succeeded after a dozen years of attempts. A print from the London Illustrated News documents the jubilant landing of the cable in Newfoundland in 1866 when the shores of England and North America were finally and soundly united.

Robert Charles Dudley. H.M.S. Agamemnon Laying the Atlantic Telegraph Cable in 1858: a Whale Crosses the Line. 1865-1866. Image and data provided by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain.

– Nancy Minty, Collections editor

-

- “Physical Geography of the Sea.” Scientific American 10, no. 29 (1855): 229. jstor.org/stable/24947961.

- Special thanks to Kelli Morgan, Associate Curator of American Art, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields who featured the Moran painting in her recent blog post, and to her colleague Linda Speight, Registration Coordinator, who shared research materials.

- From a letter, Aug. 20, 1971 to Jeffrey R. Brown, former curator of American Painting, Indianapolis Museum of Art. While Moran and others had observed the sea from above, in 1864/65 the Austrian painter Eugen von Ransonnet-Villez invented a diving bell that permitted him to draw underwater. See: Jovanovic-Kruspel, Stefanie, Valérie Pisani, and Andreas Hantschk. “Under Water” – Between Science and Art – The Rediscovery of the First Authentic Underwatersketches by Eugen Von Ransonnet-Villez (1838–1926).” Annalen Des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien. Serie A Für Mineralogie Und Petrographie, Geologie Und Paläontologie, Anthropologie Und Prähistorie 119 (2017): 131-53. jstor.org/stable/26342927

Collections

The Metropolitan Museum of Art