New collection — Open: Science Museum Group

Science Museum Group. London Midland & Scottish Railway Collection. The “Coronation Scot” train at Penrith. 1938. 1997-7409. From a set of glass and film negatives. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co423016. CC BY 4.0.

The Open: Science Museum Group collection is now available, featuring a selection of nearly 50,000 images from the Science Museum Group (UK) under Creative Commons licenses that span science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine.

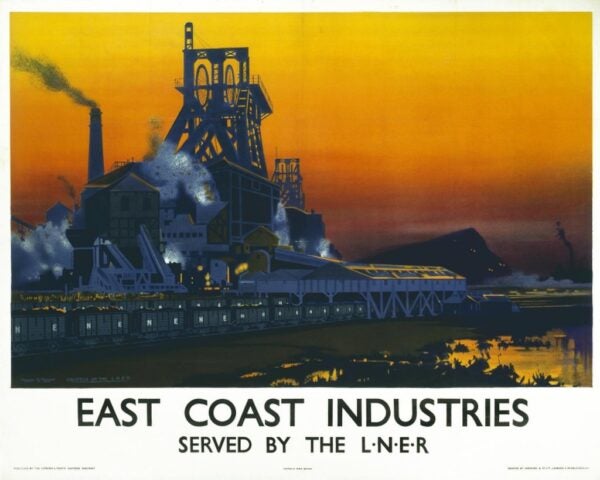

Science Museum Group. Frank Mason. East Coast Industries. London & North Eastern Railway. 1938. Poster. 1983-8415. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed October 17, 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co229864. CC BY 4.0.

Comprising the world’s leading group of science museums, the SMG consortium includes the Science Museum in London, the National Railway Museum in York, the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, and the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester and Locomotion in Shildon. Characterized as the “home of human ingenuity,” the Science Museum anchors the group. With its roots in the Great Exhibition of 1851, the Museum embodies the optimism and faith in science that was shared by its founders. To quote Prince Albert, heralding the exhibition: “Science discovers these laws of power, motion and transformation; industry applies them to the new material which the earth yields us in abundance.” [1]

The collection in Artstor presents the diverse holdings across these repositories and captures the promise characterized above: A photograph of a shining locomotive, the Coronation Scot, 1938, embodies the excitement generated by technology and ingenuity (and offers a glimpse of the wealth of material available for trainspotters). Likewise the promise of industry, rather than its scourge, is defined in the glowing poster, 1938, by illustrator Frank Mason.

- Science Museum Group. Attributed to A. E Chalon. Portrait of Ada, Countess of Lovelace. c. 1840. Watercolor. 1995-796. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed October 11, 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co67823. CC BY 4.0.

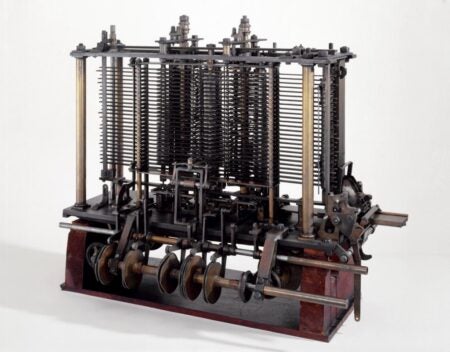

- Science Museum Group. Babbage’s Analytical Engine, 1834-1871. (Trial model). 1878-3. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed October 11, 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co62245.CC BY 4.0.

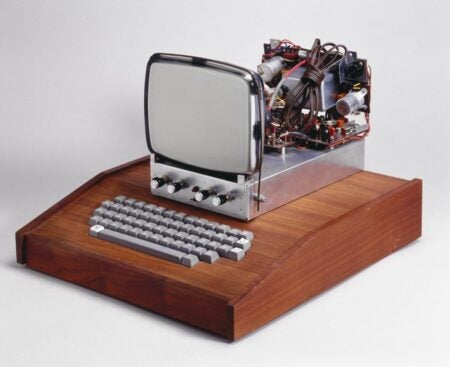

- Science Museum Group. Steve Wozniak, Steve Jobs, and Ron Wayne. Personal computer, model Apple I. 1976-1999. 1999-915. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed October 11, 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co503422. CC BY 4.0.

The development of computational science is richly chronicled in images beginning with the Analytical Engine of Charles Babbage, 1871. A watercolor portrait, Ada, Countess of Lovelace, 1840, depicts the daughter of Lord Byron, analyst and metaphysician who interpreted the Engine in her visionary Notes that include the elegant proposition: “The Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves.” Modern computing is epitomized by the personal computer, model Apple I, devised by Steve Wozniak, Steve Jobs, and Ron Wayne, 1976-1979.

- Science Museum Group. Charles Delagrave. Plaster model of a surface generated by a semi-circle, 1876. 1876-414. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co60804. CC BY 4.0.

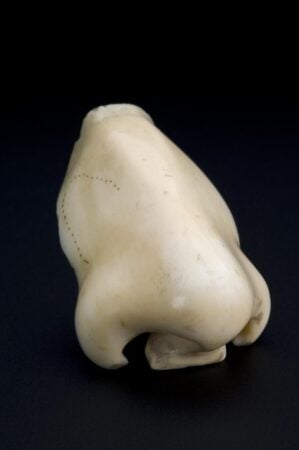

- Science Museum Group. Ivory artificial nose, Europe, 1701-1800. A641030. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co126940. CC BY 4.0.

- Science Museum Group. Stirn’s Detective Camera, 1892. 1950-92. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co15187. CC BY 4.0.

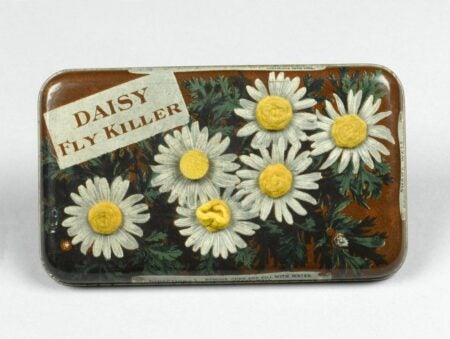

- Science Museum Group. Fly killer, New York, United States, 1888-1930. A661038. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed 18 October 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co147664. CC BY 4.0.

The expected is enhanced by the improbable in images that present the unfamiliar: a pristine model of a surface generated by a semi-circle, 1876, by Charles Delagrave, resembles a modernist staircase; an ivory prosthetic nose, 18th century, reveals the skill of a master carver; Stirn’s Detective Camera, 1892, the stealth of a spy; and a tin of “Daisy” fly killer, 1888-1930, the cunning of a criminal.

Last, but not least, behold the powder insufflator, an instrument used in Asia to administer medicated powders.

Science Museum Group. Powder insufflator. A645066. Science Museum Group Collection Online. Accessed 18 October 2019. https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co122751. CC BY 4.0.

– Nancy Minty, Collections editor

-

Cantor, Geoffrey. “Science, Providence, and Progress at the Great Exhibition.” Isis 103, no. 3 (2012): 439. jstor.org/stable/10.1086/667968.