Robert Solomon on Joseph Stapleton and his 300 self-portraits

A unique offering from a second-generation Abstract Expressionist

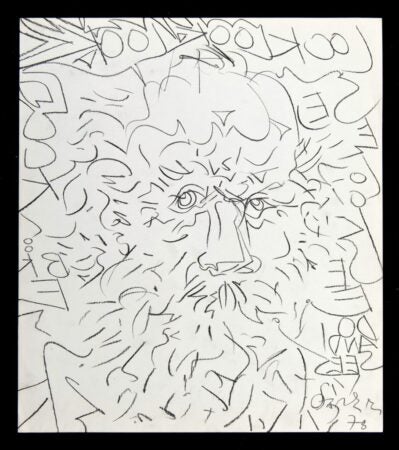

Joseph F. Stapleton. Look look. 1978. China marker, vellum. RISD Museum. Image and data provided by Robert Solomon Art.

Art historian Robert Solomon has just contributed the Joseph Stapleton: Self-Portraits collection to Artstor. Below, he provides a perspective on the artist and his significant output of self-portrait drawings.

Joseph Stapleton (1921-1994) was one of an estimated 400 artists who poured into New York City’s Tenth Street area following the close of World War II. According to historian Irving Sandler, they were attracted to this specific location by the presence of, among others, Willem de Kooning’s studio. Sandler referred to this group of artists born between 1920 and 1930 as Abstract Expressionism’s second generation. Over the next twenty years this second generation would be impacted by a variety of economic and social influences. These conditions would produce only a handful of names we recognize today.

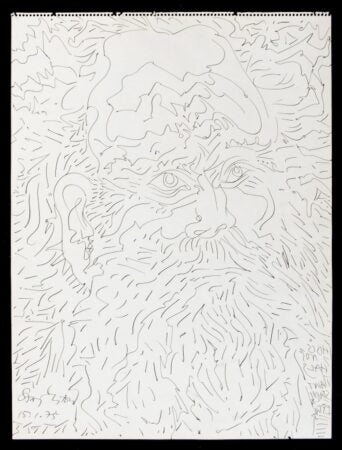

- Joseph F. Stapleton. This is not Hals It ain’t Stapleton either. 1975. India ink, bristol. Image and data provided by Robert Solomon Art.

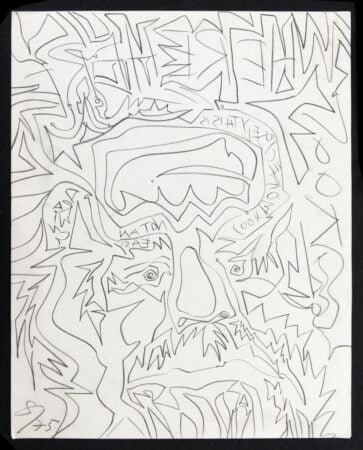

- Joseph F. Stapleton. Look more closely this is not an easy drawing. 1975. China marker, bristol. Image and data provided by Robert Solomon Art.

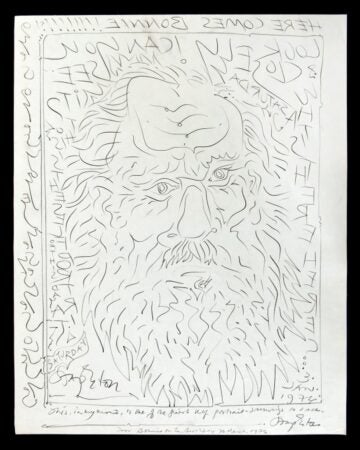

- Joseph F. Stapleton. Look closely! Can you see it? 1976. China marker, bristol. Fairfield University Art Museum. Image and data provided by Robert Solomon Art.

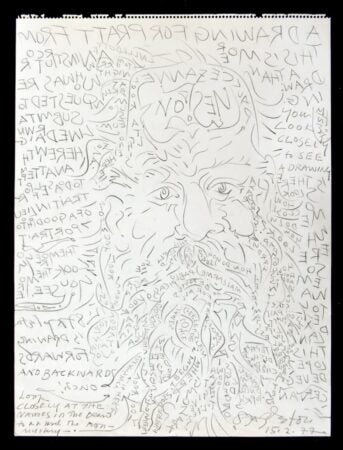

- Joseph F. Stapleton. A drawing for Pratt… 1977. China marker, bristol. Image and data provided by Robert Solomon Art.

After earning his summa cum laude double degree in Romance Languages and Sociology at St. John’s University, Joe Stapleton then served as an intelligence officer and interpreter for General MacArthur in Tokyo. Upon his return to New York he joined many of his peers in enrolling at the Art Students League. From 1947 to 1953 Stapleton studied at the League with Will Barnet, Carl Holty, Morris Kantor, Vaclav Vytlacil, Ivan Olinsky, and F.V. Dumond. During this period, he also endeavored to broaden his scope of influencers by attending meetings at Philip Pavia’s Eighth Street Club, and imbibing at the infamous Cedar Tavern. Over the next few years, he developed relationships with Pavia, Hans Hofmann, Elias Goldberg, James Brooks, Steve Wheeler, George McNeil, Friedel Dzubas, Theodoros Stamos, and many others of the first generation.

Stapleton had undergone rigorous training in life drawing during his grammar school and high school years, attending a special program at Pratt. He earned multiple awards over this period for portraiture and figure drawing. This early work caught the attention of the WPA’s Abram Lerner (later to become the Hirshhorn Museum’s first director), who enrolled Stapleton in evening anatomy classes, which he attended weekly from the mid- to late 1930s.

Despite his early proficiency, Stapleton, still a high school student, sought to further enhance his mark making by immersing himself in Zen and Japanese calligraphy. In addition to studying the work of Hiroshige, Sesshu, and Sung, Stapleton would spend his afternoons after school at the New York Public Library’s 5th Avenue branch deeply entrenched in kaisho, gyosho, and sosho practice books. This self-directed research, combined with his growing reverence of Arshile Gorky, would have a major impact on Stapleton’s extraordinary line work.

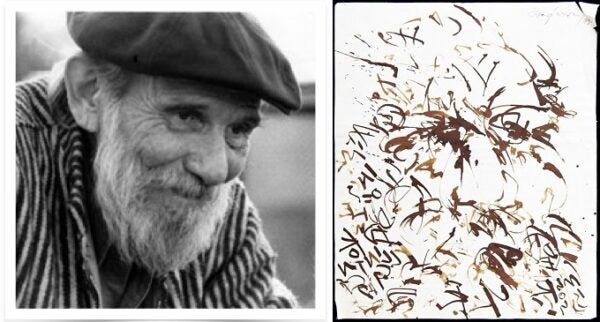

(Left) Portrait of Joseph Stapleton. Photographer unknown. Mid 1970’s. (Right) Joseph F. Stapleton. Thinking of Duke Ellington. 1979. India ink, parchment. McMullen Museum of Art. Images and data provided by Robert Solomon Art.

This collection consists of 293 self-portraits, each exhibiting Stapleton’s highly intelligent mark-making process reflective of those long afternoons studying Japanese calligraphy. As a comparison, we retain less than 100 self-portraits from Rembrandt’s oeuvre.

Characterized by incisive, economical contour, Stapleton’s impressive drawings deserve to be more widely known. Within the narrow confines of a repeated self-portrait format, Stapleton was able to demonstrate a surprising variety of touch… Jonathan Ribner, Director, Graduate Admissions, History of Art and Architecture, Boston University; Associate Professor, Nineteenth Century and Modern Art

As you view the collection, see especially the over 100 calligraphic self-portraits. No other New York School artist worked in this manner. These powerful drawings were created during a difficult ten-year period of Stapleton’s life, following the tragic 1971 Memorial Day Weekend suicide of his close friend, German Expressionist Jochen Seidel. Friedel Dzubas had introduced the two in 1966 at a time when Seidel was beginning to experiment with text. It’s important to note that over the course of their six-year friendship, Seidel had enlightened Stapleton to concrete poetry. Seidel’s tragic death drove Stapleton to deeper alcohol dependency, and the resulting depression caused him to search for inward meaning. Two years later, the calligraphic self-portraits began to appear.

Five of these calligraphic self-portraits are represented here, including examples from the RISD Museum, the McMullen Museum at Boston College, and the Fairfield University Art Museum.

Robert Solomon is the rights holder to the Joseph Stapleton Drawings Collection and a specialist in mid-twentieth-century American art; specifically, the first- and second-generation artists of the New York School. While attending Pratt in the early 1970s, Solomon (MFA Tufts University, BFA Pratt Institute) studied painting and drawing with Joe Stapleton, and then was mentored by the artist for many years. In 2013, believing Stapleton deserving of historical recognition, Solomon obtained authorization from Stapleton’s partner of 30 years, Bonnie Re, and from Stapleton’s surviving family, to conduct biographical research for a book. The family also granted to Solomon exclusive access to Stapleton’s portfolio of never exhibited drawings, which were removed from the artist’s Tribeca studio and placed into storage upon his death. In 2017, the family assigned to Solomon all rights to the collection.