Hilary Mantel and the court of Henry VIII: putting pictures to words

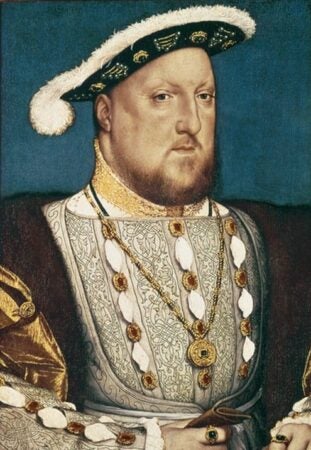

Hans Holbein the Younger. Henry VIII of England. 1536. Oil on oak. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Image and data from Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

Hans Holbein the Younger. Thomas Cromwell. c. 1532-1533. Oil on oak. Image and data from The Frick Collection.

More than 3 million of the images in Artstor are now discoverable alongside JSTOR’s vast scholarly content, providing you with primary sources and vital critical and historical background on one platform. This blog post is one of a series demonstrating how the two resources complement each other, providing a richer, deeper research experience in all disciplines.

The Wolf Hall trilogy by Hilary Mantel presents the Tudor court in arresting, vivid prose1. Nonetheless, the temptation to illustrate Mantel’s account is irresistible given her invocation of the painter “Hans” (the actual historical figure of Hans Holbein the Younger, 1497/8-1543). He appears frequently in her narrative and is her acknowledged muse: Simply put, in the author’s own words: “He [Holbein] peoples the early Tudor court for us.”2 Since Holbein the Younger was so prolific and precise as a portraitist,3 his likenesses provide a visual Who’s Who to Mantel’s narrative. Below, we have coupled some of Holbein’s most penetrating portrayals of the key players with the descriptions of the author.

Henry VIII may be the celebrity king who towers over the court, looming large in physical stature, long on spectacle, bluster and bullying, while falling short on character and compassion. But it is the humbly born lawyer Thomas Cromwell who rises to wield great power — lord, baron and chief minister — and who anchors Mantel’s narrative.

The German/Swiss native Holbein, who became painter to Henry VIII around 1536, depicted the king in monumental and intimate formats though many of his works were lost and are only known in copies. His Henry VIII of England, 1536, is the bust length version of a larger work, showing the king, aged 45, in regal trappings – bejewelled, befurred and brocaded, but undeniably in physical decline, a transition that Mantel characterizes as a deterioration — “from golden boy to wreck.” Nonetheless, near the end of the last book, Mantel still invokes the vigor of the king as he prosecutes at the trial of an ill-fated preacher. The author’s description appears to derive from a lost full-length portrait of the king, from which the crisp version above was taken: “The day is dark but Henry is wearing white from head to foot. He looks like a mountain that one hears of in fables, made of solid ice.” (The Mirror and the Light)

Henry’s loyal and crafty minister is best known to us from a portrait at the Frick Collection, Thomas Cromwell, c. 1532-1533. He rose from humble origins to accrue titles, and authority before he met the monarch’s displeasure. In Mantel’s telling Holbein “grumble[d] about Cromwell as a recalcitrant subject.” Nonetheless, we can infer his capabilities from the artist’s rendering. As the author tells us: “He can draft a contract, train a falcon, draw a map, stop a street fight, furnish a house and fix a jury.” (Wolf Hall)

- Wenceslaus Hollar after Hans Holbein. Anna Bullen Regina Angliae. 1649. Etching. Image and data from the Folger Shakespeare Library. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

- Hans Holbein the Younger. Jane Seymour. 1536. Oil on oak. Kunsthistorisches Museum. Image and data from Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

- Hans Holbein the Younger. Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan. 1538. Oil on oak. Image and data from The National Gallery.

- Hans Holbein the Younger. Anne of Cleves. 1539. Parchment mounted on canvas. Musée du Louvre. Image and data from Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

A succession of four of Henry’s six wives occupies center stage in the trilogy, the most infamous being Anne Boleyn, who was executed after a brief reign of three years, ostensibly for treason but seemingly because of her inability to produce a male heir. In her own turn, Anne had deliberately displaced the first, Queen Katherine of Aragon. Here, we purport to know Anne’s likeness from an etching by Wenceslaus Hollar after a painting by Holbein, Portrait of Anne Boleyn, 1649. (In fact the only universally accepted portrait of this queen is a medallion, 1534, British Museum). While the sitter’s identity may be contested, her likeness stands in very well for the the features defined in Mantel’s description: “a calculating being, with a cool slick brain at work… glancing around with her restless black eyes, eating nothing, missing nothing, tugging at the pearls around her little neck.” (Wolf Hall).

Anne’s ready successor and Henry’s third wife, raised to favor by Cromwell, is represented here by Jane Seymour, 1536, a painting that was made the same year that Anne was executed. Jane, who had worked at the courts of the first two queens, was selected by the king for her perceived innocence, an impression that prevailed even after her demise, post childbirth: “When Henry talks about Jane, he blinks, tears spring to his eyes. ‘Her little hands… Her little paws, like a child’s. She has no guile in her. And she never speaks. And if she does I have to bend my head to hear what she says.’” (Bringing Up the Bodies)

Following Anne’s early demise, the King sought a foreign alliance from a potential spouse. Here Holbein facilitated promising matches by making betrothal portraits of faraway sitters to bring before the King to inform his choices. In 1538, a widow, age 16, sat for Holbein in Brussels. The final painting, derived from the initial drawing, is one of the artist’s finest works. Life-size, and crafted with great clarity and subtlety, on panel, it is his Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan, 1538. While the match never took place, Mantel indicates the importance of the likeness in an exchange between the painter and the King about the drawing: “Christina is straight and tall , clear-eyed. When I have made the painting, … you will see she is so young she has dew on her. She is grave, she is poised: but there was a hint of a smile. You imagine she might put down the gloves that she twists in her fingers, and slide a warm palm against yours …[S]he has three languages besides Latin. She speaks softly, gently, in all of them, and lisps a little.” Finally, it is the portrait that Henry cherishes rather than the Duchess: “Only I regret the Duchess of Milan… And I am sorry I never saw her with my own eyes… But you can tell Master Holbein I am pleased with his picture of the Duchess Christina. I think she is standing in the room, and about to speak to me. Tell Hans I shall not part with it. I shall keep it to look at.” (The Mirror and the Light)

The King’s final match in the trilogy is with Anne of Cleves and it ends in an annulment. Hans dutifully goes to Germany where he produced a portrait for Henry, Anne of Cleves, 1539. While the painting seems to have pleased the King, Anne and he were personally incompatible and the marriage a failure. Once again, the narrative bespeaks the importance of the artist: “He [Cromwell] steps back to admire her, a shining princess who is more metal than flesh. Her clothes mould her, like the armour of some goddess, and look as if they would stand up by themselves. You drag your eyes upwards from her gleaming breastplate to her face. It is a serene oval, vulnerable, bare. It is not so young and rosy as Christina’s, but shows a modest charm. She has tender eyes, veiled: the Holy Virgin, brooding over her unexpected turn of fortune. ‘ Henry should like her,” the painter says. ‘I would. You would. It is a good picture. You would not guess how I sweated over it.’ “ (The Mirror and the Light)

George Peter Alexander Healy, after Marcus Geeraerts the Younger. Elizabeth I, Queen of England and Ireland in 1558 (The Rainbow Portrait), detail. 1844, after original from c. 1600. Oil on canvas. Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. Image and data from Réunion des Musées Nationaux / Art Resource, N.Y.

Hans Holbein the Younger, German. Edward VI as a Child. 1538. Oil on panel. Image and data from The National Gallery of Art.

While the king’s offspring do not figure prominently in the narrative, they do include future rulers, among them Anne’s daughter, the formidable Elizabeth I who grew up to govern England from 1558-1603, seen here in a copy after the celebrated Rainbow Portrait, and Jane’s son Edward VI, who reigned briefly before he died at the age of 15, as shown in Edward VI as a Child, 1538, looking every bit the infant heir to the throne.

Hans Holbein the Younger. Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve (‘The Ambassadors’). 1533. Oil on oak. Image and data from The National Gallery, London.

No single painting better embodies the intrigue, mystery and machinations of the Mantel trilogy than Holbein’s Ambassadors, 1633.4 Not only are its subjects, the French diplomats Jean Dinteville (at left) and Georges de Selve, embedded in the narrative, the author has publicly proclaimed the painting itself as her inspiration. Like the Christina portrait, the work presents the sitters standing life-sized before us. Their sumptuous, layered attire and their meticulous trappings overwhelm the eye while they call for closer scrutiny. Mantel’s description of Dinteville, by then disgraced and in exile, as seen through the eyes of Cromwell, befits the latter teetering at the height of his power but seeking comfort most of all: “He [Cromwell] thinks of the ambassador, muffled in his furs, splendid as Hans painted him: the broken lute string, the skull badge he retained in his cap. He [Cromwell] says. ‘If he were here with us today, he would be shivering, and hastening home to a good fire and spiced wine.’ “ (The Mirror and the Light)

— Nancy Minty, collections editor

1 Wolf Hall, 2009; Bringing Up the Bodies, 2012; The Mirror and the Light, 2020.

2 J.S. Marcus. “Portraying the Tudors, then and now”, Wall Street Journal, March 27, 2020.

3 Sara N. James. “Image Making and Image Breaking: Art under the Tudor Monarchs. Henry VIII, Edward VI, and Mary I, 1509–1558.” In Art in England: The Saxons to the Tudors: 600-1600, 229-78. Oxford; Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, 2016. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvh1dqgx.12.

4 Kate Bomford. “Friendship and Immortality: Holbein’s “Ambassadors” Revisited.” Renaissance Studies 18, no. 4 (2004): 544-81. www.jstor.org/stable/24413498.