Indigenous Peoples’ Day

Larry Towell. USA. Albuquerque, New Mexico. 2017. Powwow ground… Indian Trader’s Market. Photograph. Image and data from Magnum Photos. © 2020 Larry Towell / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SAIF, Paris.

Since the early 1990s, communities across America have honored Indigenous Peoples’ Day—South Dakota and Berkeley, California being the leaders. Currently more than 15 states and many municipalities observe the day, and there is a resolution before Congress to declare a federal holiday. In it, Congresswoman Deb Haaland, Co-Chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus, declares: “Our resolution recognizing Indigenous People’s Day acknowledges our country’s real history and celebrates our languages, traditions, and heritage… By dedicating this day to the strength and resilience of Indigenous peoples, we condemn those who have tried to erase us, and build strength through understanding.”

Artstor marks the day with a selection of stirring works that express Indigenous cultures across the continent.1

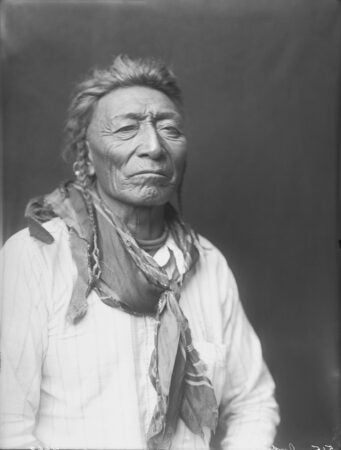

Richard Throssel. Bull Tongue in Partial Native Dress. 1910. Black and white gelatin glass negative. Image and data from National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Richard Throssel. Portrait of Fannie Anderson (Mrs Clifford Takes the Horse). 1910. Photoprint Image and data from National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

The concept of cultural tradition and renewal underscores the selection of images, beginning with Larry Towell’s photograph of a young man at a Pow Wow2 in Albuquerque, 2017, with an iconic image of Chief Joseph (1840-1904), courageous leader of the Nez Percé, looking over his shoulder. The nineteenth-century convention of the portraiture of Native Americans is represented by two likenesses, 1910, by Richard Throssel. Throssel was unique among his American contemporaries, like Edward Curtis who led the field in the photographic portraits of Native Americans, because his heritage was part Cree. In 1906, he was adopted into the Crow (Apsáalooke) Tribe in Montana where he remained for several years taking thousands of photographs.The woman portrayed here wears a dress studded with elk teeth, a sign of stature in the community.

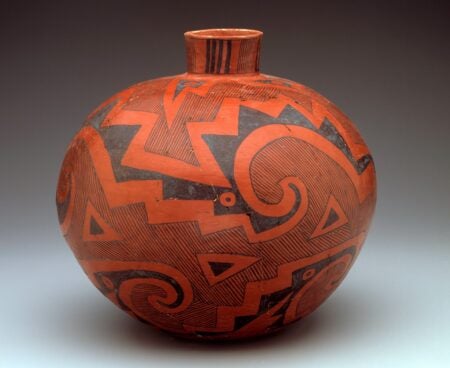

Ancestral Puebloan culture. Storage jar. c. 1125-1200. Ceramic; White Mountain Red Ware. Image and data from the Dallas Museum of Art.

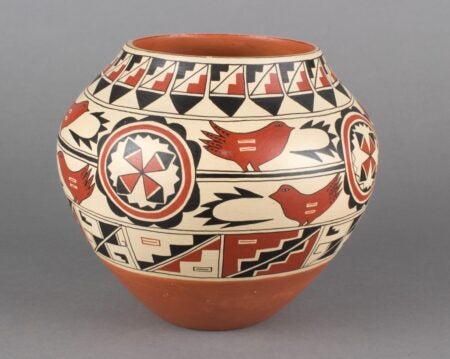

Mary Tosa. Olla. c. 1880. Glazed clay. Image and data from the Portland Art Museum.

The enduring tradition of Pueblo pottery is illustrated by the juxtaposition of the distinctive Ancestral Puebloan redware storage jar, c.1125-1200 and the water jar, c. 1880, made hundreds of years later by Mary Tosa from Jemez Pueblo.

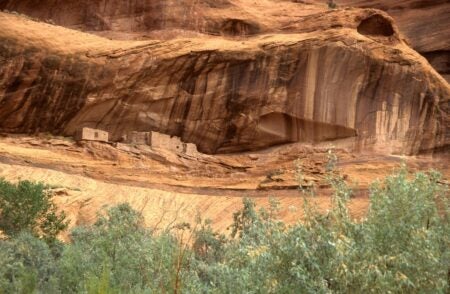

Ancestral Puebloan. Canyon de Chelly. 14th century. Canyon del Muerto, Arizona, United States. Photograph © Elizabeth Barlow Rogers.

In a photograph that merges landscape and architecture, the White House Ruin rises from the cliffs of the Canyon de Chelly (from tsegi, the Navajo word meaning rock canyon), Arizona. The canyon houses many structural remains (c. 1500 BCE – c. 1350 CE) that are now situated on a Navajo Reservation.

Douglas Cardinal, with Tetrault, Parent, Languedoc and Associates. Canadian Museum of Civilisation. 1983-1989. Photograph © Alec and/or Marlene Hartill.

Indigenous Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal (b. 1934, descendant of the Blackfoot Tribe) reprises the organic concept of architecture from the Pueblo cliffs in the striations and undulations of his design for the Museum of History, Gatineau, 1989. Cardinal also designed the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian that opened in 2004.

Assiniboin or Fox peoples. Cape. 18th CE. Painted hide. Image and data from Réunion des Musées Nationaux.

Stephen Mopope. Pochoir print of Stephen Mopope drawing of squaw dance. 1929. Image and data from the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Museum.

One of the earliest extant buffalo hide paintings from the 18th century comes down to us from an unknown artist of the Assiniboine or Fox Peoples Tribe of the Great Plains. The distinctive patterns suggest the influence of beadwork and the use of stencilling. Two centuries later the artist Stephen Mopope of the Great Plains, among the groundbreaking members of the Kiowa Five, began his training painting hides with his family. The work shown here, a pochoir print (a painting using a stencil), partakes of the artistic and technical traditions of hide paintings.

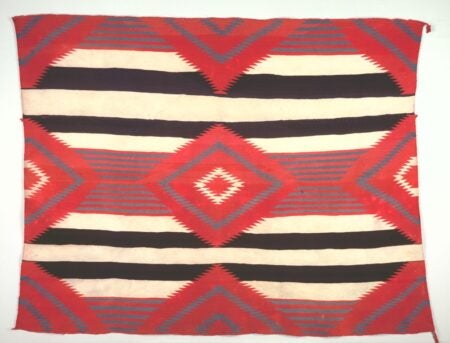

Navajo, Post-Contact, Early Period. Rug (Third-phase Chief Blanket Style, Germantown Weaving). c. 1890-1910. Image and data from The Cleveland Museum of Art. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

Unknown Navajo artist. Bracelet. Silver. c. 1940. Image and data from the Portland Art Museum.

The work of many Native American artists and artisans is endowed with a strongly geometric and linear character that links it back to belief systems and nature — a sacred design summed up by the contemporary painter Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Salish): “We are part of the earth and it is part of us.”3 The vibrant woven textiles of the Navajo, exemplified here by a rug, c. 1890-1910, work symbolic patterns into cohesive, striking designs. A silver sandcast Navajo bracelet, c. 1940, fuses a brilliant, functional cuff design with symbolic motifs like the central, opposed prayer fans.

Unknown artist, Yup’ik. Mask. 19th – 20th century. Wood, feathers, pigment. Image and data from The Minneapolis Institute of Art.

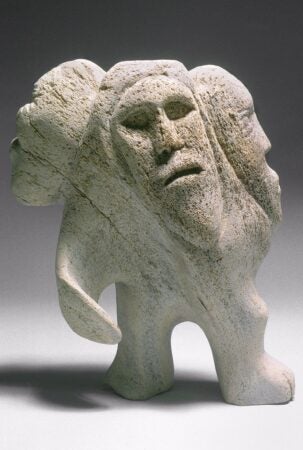

Unknown artist, Inuit. Shamanistic Spirit Figures. 1964. Whalebone. Image and data from Smith College Museum of Art.

While the artistic heritage of the Indigenous communities of the far north merits a separate study, we would be remiss if we didn’t touch on them here. The single face of the wooden Yup’ik mask and the three spirits of the Inuit shamansitic whalebone sculpture celebrate the vibrant animism that permeates their cosmos.

Happy Indigenous Peoples’ Day!

– Nancy Minty, collections editor

1For the purposes of this survey, we consider the output of tribes across North America, with the understanding that each may encompass an individual character and that there is no monolithic Native American culture. For a comprehensive introduction, see Frederick J. Dockstader. “Native American Art.” Brittanica.

2From the Narragansett word powwaw, meaning spiritual leader.

3 Quoted in Kate Morris. Shifting Grounds: Landscape in Contemporary Native American Art. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvddzv73. 2019, p. 63.

Resources from JSTOR:

Native American publication collection on JSTOR

https://www.jstor.org/site/grand-valley-state-university/native-american-publication/

Ellen C. Caldwell. Challenging Columbus Day. JSTOR Daily. 2015.

Microcosms: Sacred Plants of the Americas. St Lawrence University

https://www.jstor.org/site/stlawu/microcosms-sacredplantsoftheamericas/

Artstor collections:

- Bob Schalkwijk Photography

- Canyonlights World Art Image Bank: Art, Architecture, and Archaeology

- Ferguson-Royce Archive: Pre-Columbian Photography (University of Texas)

- Library of Congress Collection

- Magnum Photos (including nearly 200 photographs by Larry Towell documenting recent protests by Native Americans)

- Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia

- Native American Art and Culture Collection (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution)

- Panos Pictures

- Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

- Portland Art Museum