New: Open images from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Open Artstor: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture is now available in Artstor, featuring a selection of approximately 2,500 images under Creative Commons licenses. This is part of an initiative to aggregate open museum, library, and archive collections across disciplines on both resources. We are proud to present this content, along with the freshly published Open Artstor: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (New York Public Library) collection as part of an ongoing initiative to bring more African American resources to JSTOR.

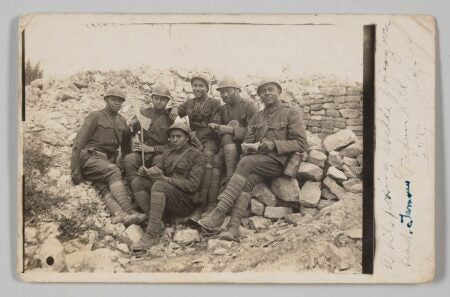

Photographic postcard of soldiers in World War One at Verdun. July 1918. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

Established by an act of congress in 2003 and opened in 2016, the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) is devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life. The current selection of images in Artstor represents a broadly based interpretation of the culture, with diverse narrative histories including enslavement and emancipation, protest and civil rights movements, and the lives of celebrated citizens and everyday people. It provides most of the museum’s online offerings including photography, art, artifacts, fashion, musical instruments, letters and cartes de visite, books, broadsheets, political buttons, and all types of ephemera, collectively portraying the lives of African Americans from around 1700 to the 2010s. The eclectic and dynamic perspective provided by this varied collection is summed up by the museum’s incoming Director, Kevin Young. In a recent interview the poet, author, essayist and editor characterized the museum’s mission:

We’re in history now, and that history is a living thing…Think about the art people are making, the conversations people are having. That’s where we can collect and connect and help people see the bigger picture… We’re thinking about what that history means, but also the power of joy and pleasure.” 1

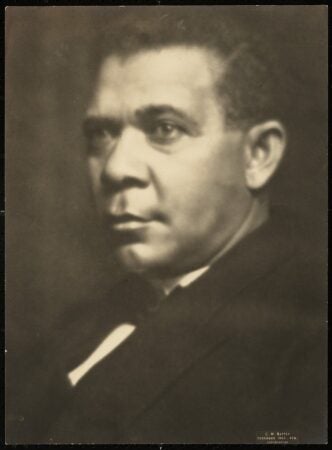

- C. M. Battey. Booker T. Washington. c. 1908. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

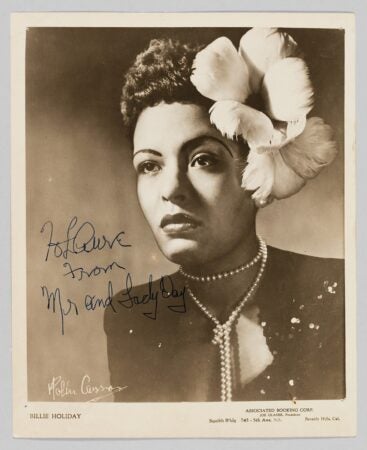

- Robin Carson. Photograph of Billie Holiday. c. 1940. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

Photography is the central witness to history in the museum’s holdings. A varied albeit small sampling reveals the reach of the collection: soldiers pose with great composure on the rubble at Verdun, 1918 (an inscription states “while passing shells going over head”) — members of the African American 372nd Infantry Regiment that fought with the French and were awarded the Croix de Guerre; the solemn countenance of Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute, captured in a portrait by the African American photographer Cornelius M. Battey, one of the first Black portraitists to gain recognition; a vision of c. 1940, jazz legend Billie Holiday luminous, on the cusp of superstardom, in a shot by society photographer Robin Carson.

Fashion — wearable culture and history — also fills an important role at the museum. The core of the collection comes from the Black Fashion Museum established by Lois K. Alexander Lane in Harlem in 1979, the bequest of her daughter Joyce Bailey, consisting of archives and around 2,000 garments.

- Ann Lowe. Dress. c. 1960. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

- William Ware Theiss. Red Starfleet uniform worn by Nichelle Nichols… 1966-1967. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

- Hands Up United. T-shirt worn by Rahiel Tesfamariam at a protest commemorating Michael Brown. 2015. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

The couture creations of Ann Lowe of Harlem are highlights, exemplified here by a black cocktail dress, c. 1960, a silk, chiffon, and taffeta confection with an applique neckline of hand sewn roses and leaves. In contrast, a bold red velour and gold braid mini-dress is unmistakable as the uniform of Star Trek’s Lt. Uhura played by Nichelle Nichols in a ground-breaking television role for an African American woman. Fashion shifts from the decorative to the declarative with the T-shirt that proclaims “This Ain’t Yo Mama’s Civil Rights Movement.” Activist Rahiel Tesfamariam donated the shirt that she wore to a protest in Ferguson on the first anniversary of the shooting of Michael Brown. The shirt was made by Hands Up United, and the slogan paraphrases the words of rapper Tef Poe, co-founder of the movement.

Pinback button of the Pan-African flag. Mid-20th century. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

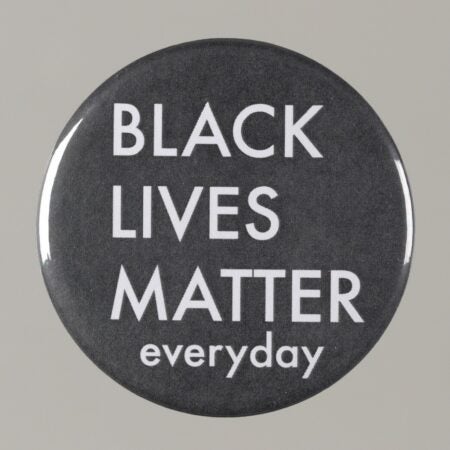

Pinback button stating “Black Lives Matter Everyday.” 2015. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

Pinback buttons form another subcollection at the museum with hundreds of examples. Originally developed as messengers of political propaganda in the late 1900s, they have been adapted as tiny yet powerful platforms for proclamation and reform. The colors of the Pan-African flag shine like a beacon in a pin dating to the mid 20th century, while the “BLACK LIVES MATTER everyday” button, made in 2015 for the 20th anniversary of the Million Man March, repeats the call that has spread around the world since it first arose in 2013 over the injustice of the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer.

Whitehead and Hoag Company. Pinback button featuring Willie Simms. c. 1895. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

Pinback button featuring … Bessie Coleman. Mid to late 20th century. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

The buttons in the collection are also memorabilia that celebrate and preserve the personae of exceptional individuals from the African American community, exemplified here by Willie Simms and Bessie Coleman. Simms was a leading American jockey of the late nineteenth century, at a time when African Americans dominated the sport and were among the highest paid athletes — before they were largely shut out by the 1920s. “Brave Bessie” became a sensation as a female aerobatic pilot, overcoming obstacles to aeronautical training for African Americans and women domestically by pursuing her training in France.

Pauline Powell Burns. Violets. c. 1890. Image and data from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

Our introduction to the collection concludes with an intimate, delicate still life painting of violets by Pauline Powell Burns, c. 1890. Self-taught, Burns was highly regarded in her day and she was one of the first African American artists to exhibit publicly in California. This painting is among a handful of her traceable works and it is an outstanding display of her skill.

— Nancy Minty, collections editor

1 Peggy McGlone, African American Museum director Kevin Young focuses on culture and connections – The Washington Post, May 20/21.