A.A. Schomburg: Collector of lost histories

Artstor has released more than 2,000 images from The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a world-leading cultural institution devoted to the research, preservation, and exhibition of materials focused on African American, African Diaspora, and African experiences. The center was named after its chief early contributor, Arthur Schomburg. You can access this collection freely on JSTOR.

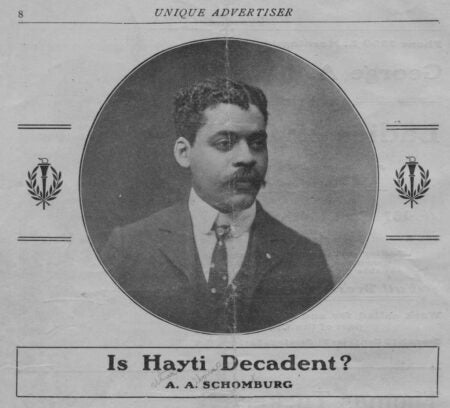

Photograph of Arthur Alfonso Schomburg. Is Hayti decadent? Issued: 1904. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

Negro life is not only establishing new contacts and founding new centers, it is finding a new soul.

— Alain LeRoy Locke, The New Negro, An Interpretation, 1925

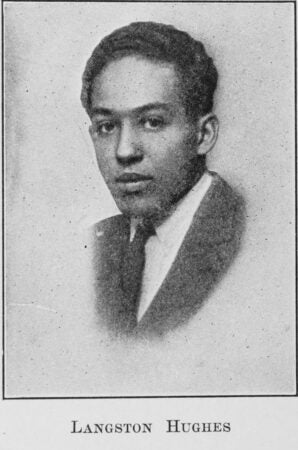

During the social upheaval that marked the Roaring Twenties, Harlem was experiencing its own revolution. As part of the Great Migration, African Americans seeking opportunities in New York City made Harlem their home. The convergence of diverse backgrounds and a new-found sense of freedom sparked an explosion of creative output in a period known as the Harlem Renaissance. Many learned of this cultural awakening from the 1925 publication of Alain Locke’s The New Negro, An Interpretation. Locke addressed this “spiritual coming of age” for the Black race with an anthology featuring such voices of change as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Thurston, Claude McKay, Jessie Redmon Fauset and the bibliophile, Arthur Schomburg.

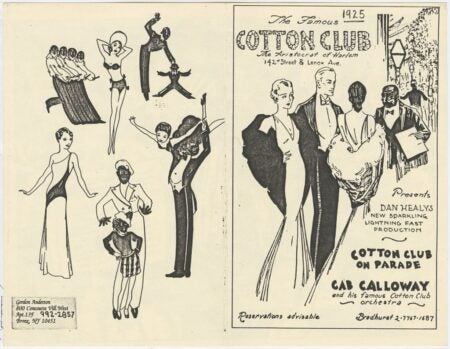

- The Famous Cotton Club presents Dan Healy’s Cotton Club on Parade with Cab Calloway and his famous Cotton Club Orchestra. Cotton Club advertisement flier. Issued: 1925. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

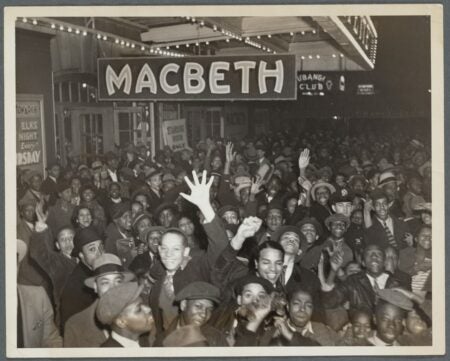

- Crowds at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem at the opening of “Macbeth”. Created: 1936. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

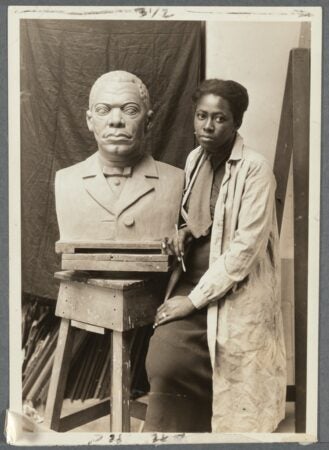

- Selma Burke. Selma Burke with her portrait bust of Booker T. Washington. Created: 1935-1943. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

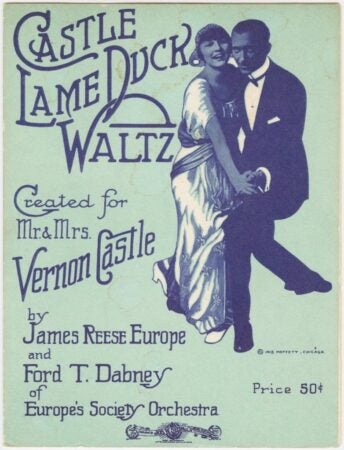

- Castle Lame Duck Waltz sheet music cover. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

Schomburg’s archival work was part of this shift in perceptions. Although he rarely had time for the diversions of The Jazz Age that drew fashionable New York to Harlem, his collection was a community resource. As the painter Aaron Douglas observed, young artists knew about Schomburg, but were too swept up in the parties and heady ideas to take much notice of the book collector, “Perhaps we were not ready for what he had to offer.”1 What Schomburg brought to the discussion was more fundamental. In 1925, he helped facilitate the opening of the New York Public Library’s Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints. The research library that would house his important collection eventually bore his name, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

There is the definite desire and determination to have a history… as a stimulating and inspiring tradition for the coming generations.

— Arthur Schomburg, “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” 1925

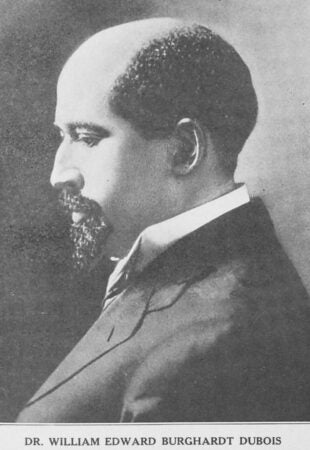

- Dr. William Edward Burghardt DuBois. Issued: 1923. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

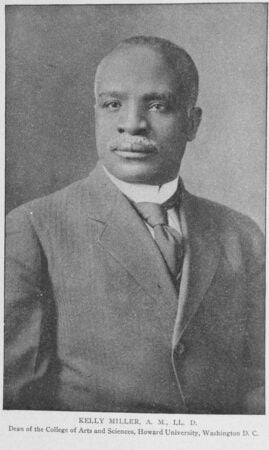

- Kelly Miller, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Howard University, Washington, D.C. Issued: 1917. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

- Langston Hughes. Issued: 1923. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

- Kerlin, Robert Thomas, 1866-1950 (Author), Publisher: Associated Publishers. Jessie Redmon Fauset. Issued: 1923. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

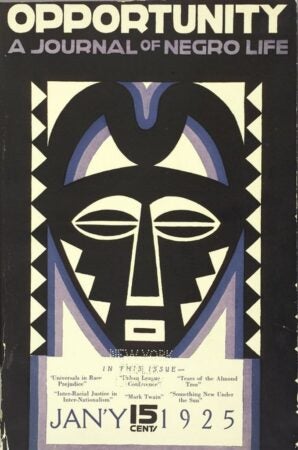

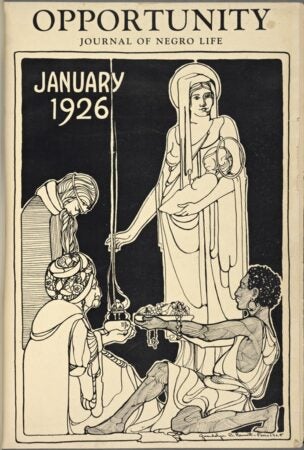

- National Urban League (Publisher), Johnson, Charles Spurgeon, 1893-1956 (Editor), Publisher: National Urban League, etc. Opportunity: journal of Negro life, January 1925, [Front cover]. Issued: 1925-01. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

- National Urban League (Publisher), Johnson, Charles Spurgeon, 1893-1956 (Editor) Bennett, Gwendolyn, 1902-1981 (Artist), Publisher: National Urban League, etc. Opportunity: journal of Negro life, January 1926, [Front cover]. Issued: 1926-01. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

Like many autodidacts, Schomburg was driven by ideas. Born Arturo Alfonso Schomburg in Puerto Rico, he often experienced racism as the son of a Black mother from St. Croix and a Puerto Rican-German father. When a teacher told him there were no history books for people like him, it triggered a lifelong pursuit to find these “missing” stories. This search eventually brought him to New York in 1891, at the age of 17, where he became a vigorous proponent of independence for Puerto Rico and Cuba. He also joined the Black freemasonry movement at a time when fellow members included the activists Booker T. Washington, Marcus Garvey, and John Edward Bruce.

Bruce, a journalist and historian, strongly influenced Schomburg with his views on Pan-Africanism. They cofounded The Negro Society for Historical Research which brought together African, West Indian and Afro-American scholars. Bruce also encouraged Schomburg to join the prestigious American Negro Academy where leading intellectuals like W.E.B. DuBois and Kelly Miller debated social theory. Schomburg welcomed the fellowship and exchange of ideas in these clubs (he was said to belong to as many as 30 organizations at one time). Not surprisingly, the Schomburg collection highlights organizations devoted to the advancement of African Americans.

I think that Arthur A. Schomburg is the antecedent of the Black Studies Revolution and one of the ideological fathers of this generation.

— John Henrik Clarke, “The Influence of Arthur A. Schomburg on My Concept of Africana Studies.” 1992

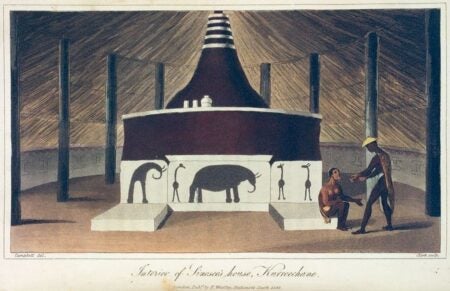

- Interior of Sinosee’s House, Kurreechane. Issued: 1822. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States

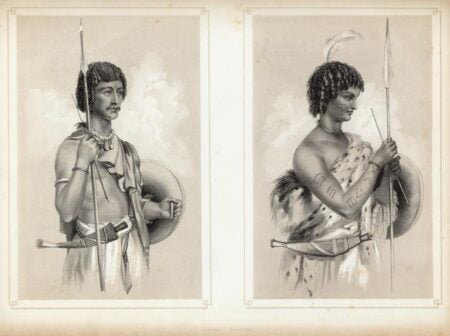

- Danakil Warriors. Issued: 1845. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

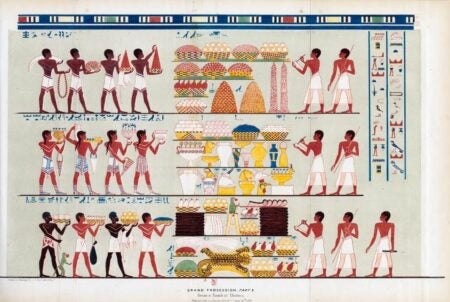

- Grand Procession. Part 2. From a Tomb at Thebes. Issued: 1835. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

Schomburg’s intellectual pursuits were part of an early twentieth century movement that challenged prevailing historical narratives scholars believed either ignored or discounted Black achievements. Collecting works to offset these omissions was seen as a form of activism. Many of these archivists focused on U.S. events. Schomburg, who identified himself as an Afro-Puerto Rican, advocated a broader view that encompassed all people of African descent. Given this scope, he is said to have established the first substantial transnational Black collection.

With his limited budget, Schomburg’s focus on objects from the African diaspora was a challenge. His networks were invaluable resources for local acquisitions, but securing works from other countries required creativity. As a Wall Street mail clerk, he parlayed international contacts into referrals; he also relied on colleagues. Civil rights activist, James Weldon Johnson, was known to receive last minute instructions from Schomburg before departing for Central or South America. The African American opera singer, Caterina Jarboro, sent back rare items from her European tours. Langston Hughes forwarded poetry from Madrid and Mexico, as well as memorabilia of Jesse Owens’ momentous win at the Berlin Olympics.

From neglected and rust-spotted pages comes testimony to the black men and women who stood shoulder to shoulder in courage and zeal…

— Arthur Schomburg, “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” 1925

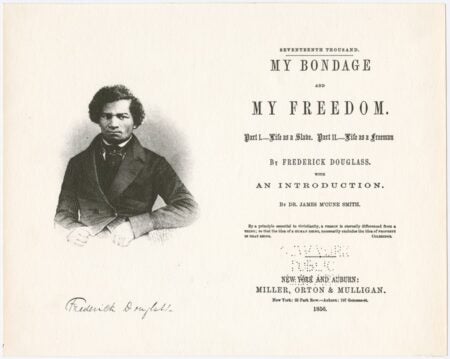

- Publisher: Miller, Orton & Mulligan. Frontispiece and title page of “My Bondage and My Freedom” Print Collection portrait file. Issued: 1856. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

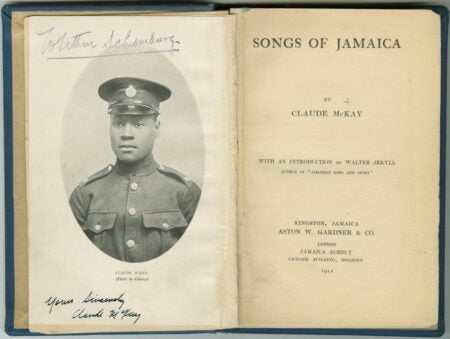

- Songs of Jamaica by Claude McKay; Title page signed by the author for Arthur Schomburg. Songs of Jamaica. Issued: 1912 Created: 1912. Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

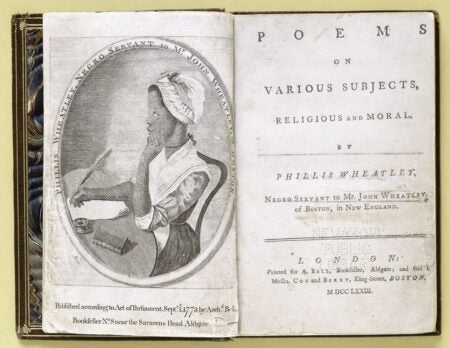

- Wheatley, Phillis, 1753-1784 (Author) Publisher: Printed for A. Bell, bookseller, Aldgate. Title page and frontispiece, Poems on various subjects, religious and moral by Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753-1784). Issued: 1773-09-01 Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

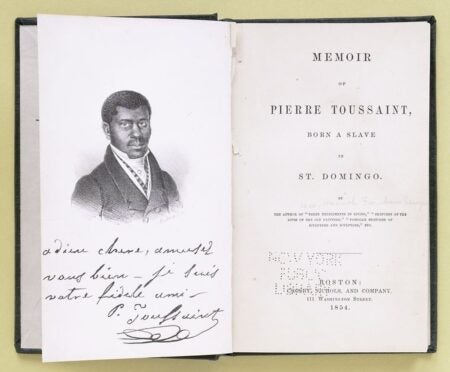

- Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, [Frontispiece with inscription and title page] Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, born a slave in St. Domingo. Issued: 1854 Image and original data from the New York Public Library. No Copyright – United States.

As a result of his perseverance, Schomburg amassed an amazing trove of artwork, artifacts and writing that featured figures or cultures little known at the time. His reputation as an intellectual also grew; he was often invited to speak or write about his finds. He frequently expressed his views in letters to the editor of The New York Times and his articles appeared in The Crisis, Opportunity, and The New York Amsterdam News.

By 1926, his extensive archive was broadly acknowledged for its value to scholarship, and he had received several offers. It was said his wife gave him an ultimatum: either the collection or his family had to move out of their cramped Brooklyn home. The purchase by the New York Public Library of this content for its 135th Street branch was welcomed by the bibliophile, who wanted it to remain available to Harlem youth. Schomburg promptly used the $10,000 payment to finance additional collection work overseas. It’s estimated that his contribution included 5,000 books; 3,000 manuscripts; 2,000 etchings and paintings; and several thousand pamphlets.2

Schomburg remained active at the research library and in 1932, he was made curator of his collection. In deference to his expertise, many of the staff and regulars referred to him as “Doctor” Schomburg, despite his lack of a formal education. Following his death in 1938, the Library made the popular decision to rename the Division after its early benefactor. Since receiving his early seed collection, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture has developed into a renowned repository with holdings of 11 million items and an international reputation for its focus on the African American, African Diaspora, and African experience.

— Lee Caron, Primary Sources Editor

1 Interview with Aaron Douglas, Nov 13 1973, Fisk University, Nashville, Tenn. quoted in E.Sinnette, Arthur Alfonso Schomburg, Black Bibliophile & Collector: A Biography (New York Public Library & Wayne State University Press, Detroit 1989), p. 134

2 “About the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.” New York Public Library website

Readings from JSTOR

Clarke, John Henrik. “The Influence of Arthur A. Schomburg on My Concept of Africana Studies.” Phylon (1960-) 49, no. 1/2 (1992): 4–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3132612.

Hoffnung-Garskof, Jesse. “The Migrations of Arturo Schomburg: On Being Antillano, Negro, and Puerto Rican in New York 1891-1938.” Journal of American Ethnic History 21, no. 1 (2001): 3–49 https://www.jstor.org/stable/27502778.

Holmes, Eugene C. “Alain Locke and the New Negro Movement.” Negro American Literature Forum 2, no. 3 (1968): 60–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/3041375.

Holton, Adalaine. “Decolonizing History: Arthur Schomburg’s Afrodiasporic Archive.” The Journal of African American History 92, no. 2 (2007): 218–38. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20064181.

Schomburg, Arthur A. “The Negro Digs Up His Past (1925).” The New Negro: Readings on Race, Representation, and African American Culture, 1892-1938, edited by Henry Louis Gates and Gene Andrew Jarrett, Princeton University Press, 2007, pp. 326–29, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1j6675s.61.

Other sources

Locke, Alain. 1925. The New Negro An Interpretation. New York. Albert and Charles Boni, Inc..

Sinnette, Elinor Des Verney. 1989. Arthur Alfonso Schomburg, Black Bibliophile & Collector: A Biography. Detroit. New York Public Library & Wayne State University Press.