Genius has no gender*: Rethinking the Old Master moniker

Artemisia Gentileschi. Esther before Ahasuerus. Oil on canvas. Image and data from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Once upon a time–not so long ago–it seems that we believed that all the great pre-modern western painters were men! If not, why did we call them the Old Masters? The honorific derives from the masculine latin term magister meaning teacher, master, chief, coming from magis–more or greater. By definition and origin, the concept excludes women. Since the late 1900s the term has become so pervasive that a title search for old masters returns 74,000 + hits on WorldCat. Notwithstanding false results and the many auction catalogs, a lot of ink has been spilled on the Old Masters.

Seriously though, there have been many scholars, notably women, who have labored to dispel this myth. Beginning with the trailblazers Linda Nochlin’s “Why have there been no great women Artists?” and Old Mistresses, women art and ideology by Griselda Pollock and Rozsika Parker, the pendulum started to swing back and women artists began to take their rightful places. Women’s History Month provides an opportunity to revisit some of these “rediscovered” creators and their accomplishments. We already know their names: Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Leyster, Rosa Bonheur… Thankfully, they are celebrated today, and it’s always worth taking another look; after all, how many times have we lauded their counterparts the Old Masters? Of course, the current small selection under-represents women painters, but it is intended here as a temporal counterpart to the Old Masters and as an indication of far greater numbers. Apologies to the many artists unmentioned, particularly to contemporary figures.

- Artemisia Gentileschi. Judith and Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes. c. 1625. Oil on canvas. Image and data from The Detroit Institute of Arts.

- Sofonisba Anguissola. Game of Chess…1555. Oil on canvas. Image and data from Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

- Sofonisba Anguissola. Alessandro Farnese. c. 1561. Oil on canvas. Image and original data provided by Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

Let’s begin with Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c. 1654), the most recognized female painter of the Baroque era. The Roman-born daughter of a painter, she worked throughout Italy and even in England. Strong women were Artemisia’s speciality. She is represented here by a sweeping history painting of the biblical heroine Esther and a painting of the Old Testament protagonist Judith. In modern scholarship she was first brought to light by feminists Germanine Greer and Mary Garrard. In 2020, she was the first woman in the 197-year history of the National Gallery, London to be celebrated with a solo exhibition.

Sofonisba Anguissola (1532-1625) was the most accomplished of six artist sisters. She worked at the royal court in Madrid, specializing in portraiture. In The Game of Chess, three of the painter’s sisters are portrayed with warmth and candor, while the single portrait of Alessandro Farnese is more formidable and guarded. All of the sitters are attired in characteristically splendid detail. On her death at the age of 93, Anguissola’s husband composed her epitaph: “To Sofonisba, my wife, who is recorded among the illustrious women of the world, outstanding in portraying the images of man.” The scholars Garrard, Pollock, and Parker have also ensured her place in the pantheon, and she was recently honored by an exhibition at the Prado.

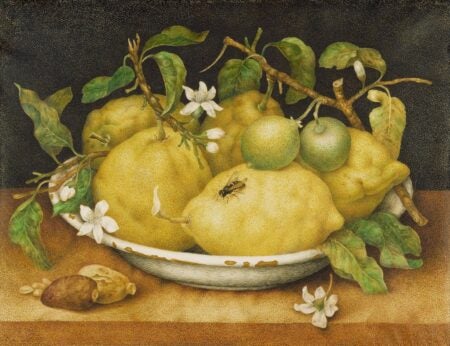

- Giovanna Garzoni. Still Life with Bowl of Citrons. Late 1640s. Tempera on vellum. Image and data from The J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Maria Sibylla Merian. Still life with fruit. Bodycolor on parchment. Image and data from Berlin State Museums (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin).

- Rachel Ruysch. Still Life with Flowers in a Glass Vase. 1690-1720. Oil on canvas. Image and data from the Rijksmuseum.

Scientific observation and precision governs the art of the next three practitioners: Giovanna Garzoni, Maria Sybilla Merian, and Rachel Ruysch. Born in the region of Le Marche, Garzoni (1600-1670) worked at the Medici court in Florence producing botanical and zoological renderings, most in tempera on vellum, like the diminutive Still Life with Citrons. Another rediscovery by Mary Garrard, Garzoni’s skill was honored by a retrospective at the Uffizi in 2020. Merian (1647-1717) was a Netherlands-based naturalist, entomologist and botanical illustrator who is best-known for her brilliantly crafted treatise on insects, the Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium that she researched in Surinam and completed with the assistance of her two daughters. Here she is represented by a Still-Life with Fruit, gouache on parchment, a fitting pendant to Garzoni’s citrons. Merian’s reputation was deliberately degraded by at least one scientific writer in the 19th century, and it was not until the 1990s that her reputation was rehabilitated by historian Sharon Valiant. She and her daughters were commemorated by an exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum in 2008. The Dutch painter Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) rose highest with a position at the court in Düsseldorf, and works fetching the richest prices on the contemporary market–mostly flower still life paintings exceeding even Rembrandt’s rates. Her training with her anatomist father and the still life painter Willem van Aelst combined the skills of art and science, perfectly suited to her immaculate yet teeming paintings like the Still-Life with flowers. The painter maintained a thriving career in a male-dominated field while raising ten children. She was documented in a dissertation by Marianne Berardi in 1998.

Judith Leyster. The Last Drop. c. 1639. Oil on canvas. Image and data from the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Elisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun. Queen Marie Antoinette. 1788. Oil on canvas. Image and data from Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives/ART RESOURCE, N.Y.

Judith Leyster of Haarlem (1609-1660) is one of a handful of known women painters who depicted genre scenes (figurative paintings from daily life, both high and low), like The Last Drop, a send-up of overindulgence. While coveted during Leyster’s lifetime, her paintings were subsequently misattributed to male artists. She resurfaced thanks to the notice of Dutch art historian Cornelis Hofstede de Groot and later, more fully due to the dissertation of Frima Fox Hofrichter. In 2009, an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art paid tribute to her work. Finally, in 2021, Leyster, Ruysch, and their Dutch sister painter Gesina Ter Borch were the first women to be included in the “Gallery of Honor” at the Rijksmuseum.

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842) was a Parisian prodigy, portraying the aristocracy in her teens and favorite painter to Queen Marie Antoinette, depicted here in luxuriant teal velvet, during her 20s. Though her fortunes fell during the French Revolution because of her Loyalist ties, she continued to paint prolifically in exile throughout Europe and finally back in her native France. She is believed to have produced more than 600 portraits, with a significant majority of female sitters. It was not until 2015 that she earned her first retrospective exhibition at the Grand Palais, Paris.

Rosa Bonheur. The Horse Fair. 1853-1855. Oil on canvas. Image and data from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

We conclude with Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), animal painter par excellence, as evidenced here by the magnificent and monumental Horse Fair. By the end of her life, her paintings numbered nearly 1,000, with the addition of hundreds of watercolors, drawings, and sculptures. In 1865, she was the first woman to be decorated as a Knight of the Legion of Honor, elevated to Officer in 1894. In spite of her acclaim, soon after her death Bonheur’s realistic, tenebrist works were eclipsed by the taste for Impressionism and they fell out of fashion. In the 1980s her critical fortunes began to rise with a biography by the critic Dore Ashton. The Musée d’Orsay is organizing a major retrospective of Bonheur’s work, fall 2022-winter 2023. It is co-curated by the Château de Rosa Bonheur, the artist’s beloved home and atelier, where a lucky visitor can experience her world first-hand.

*A paraphrase of the statement “Genius has no sex” ascribed to Empress Eugénie when she awarded the medal of the Legion of Honor to Rosa Bonheur. It derives from Mme. de Stael and George Sand.

— Nancy Minty, collections editor

COLLECTIONS IN JSTOR

Erich Lessing Culture and Fine Arts Archives

Berlin State Museums (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin)

REFERENCES

P. Briggs (2016). [Review of Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader, by M. Reilly]. Woman’s Art Journal, 37(1), 63–64. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26452062

A. K. Hamlin (2020). Telling Stories Differently: Writing Women Artists into Wikipedia. In C. Henseler (Ed.), Extraordinary Partnerships: How the Arts and Humanities are Transforming America (pp. 119–136). Lever Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3998/mpub.11649046.11

T. L. Jones (Ed.). (2021). Women Artists in the Early Modern Courts of Europe: c. 1450-1700. Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1z3hk70

L. T. Tomasi (2008). “La femminil pazienza”: Women Painters and Natural History in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries. Studies in the History of Art, 69, 158–185. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42622437