Painting for peace: Art exposes the cruelty of war

Peter Paul Rubens. Consequences of War. 1637-38. Oil on canvas. Image and data from SCALA, Florence.

The power of art to revile and denounce war may be seen in works that cross cultures and centuries. Artstor is replete with examples from the dynastic courts of Europe, to the witnesses of the American Civil War, both World Wars, Vietnam, and beyond. The selection below, featuring monumental and intimate interpretations, provides persuasive evidence of the passion for peace among artists.

The Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens painted the monumental Consequences of War in 1638-1639, one year before his death, at the end of an immensely successful career painting at the leading courts of Europe, where he also served as an agent engaged in the machinations of diplomacy. He had witnessed the destruction of decades of war across the continent. The painting, nearly ten feet wide, was made for Rubens’ friend and fellow artist Justus Sustermans, who was the official painter at the court of the Medici in Florence.

While Rubens’ lifelong engagement in political intrigue indicates that he was no pacifist in the modern sense, his description of his composition from a letter to Sustermans leaves no doubt that he intended it as an execration of war: “The principal figure is Mars [the god of war], who… rushes forth with shield and blood-stained sword, threatening the people with great disaster… Near by are monsters personifying Pestilence and Famine, those inseparable partners of War… There is also a mother with her child in her arms, indicating that fecundity, procreation, and charity are thwarted by War, which corrupts and destroys everything… That grief-stricken woman clothed in black… is the unfortunate Europe who, for so many years now, has suffered plunder, outrage, and misery, which are so injurious to everyone…” 1

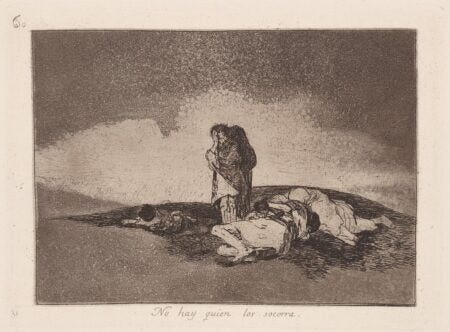

Francisco de Goya. There is no one to help them. 1810-1815 (printed 1863). Etching and aquatint. Image and data from Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University.

Spanish painter Franciso Goya’s response to the Napoleonic occupation of his country that wrought misery and destruction may be seen in the series of 82 aquatints made from 1810-1820 and published posthumously under the title Los Desastres de la guerra (Disasters of War). On completion of the series of proofs, the artist had originally given the title: “Fatal consequences of the bloody war in Spain with Bonaparte, and other emphatic caprices.” In each devastating scene, devoid of heroism, Goya encapsulates the abject violence and degradation of conflict, as in plate 60, There is no one to help them.

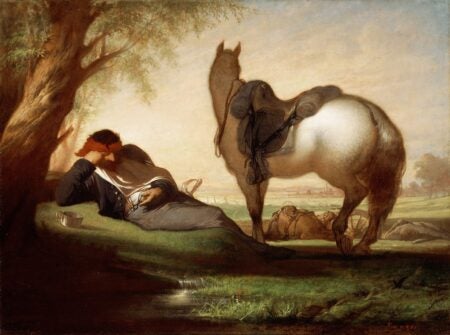

William S. Rimmer. Civil War Scene. c. 1870/1875. Oil on canvas. Image and data from The Detroit Institute of Arts.

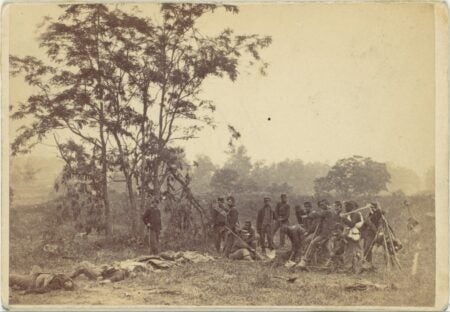

Alexander Gardner. Burying the Dead on the Battlefield of Antietam, September 1862. Albumen silver print from glass negative. Image and data from The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Creative Commons: Free Reuse (CC0).

A Civil War scene by the American painter/sculptor William Rimmer made in the artist’s final years appears at first like a quiet respite from battle — a soldier reclines while his horse rests. Closer inspection reveals that the soldier is wounded and his horse looks out over a field where the lifeless bodies of another horse and a soldier have fallen.

The same conflict provoked the first use of the camera on the battlefield in America when Alexander Gardner photographed the dead at Antietam, mere days after the fighting had ceased. In his Burying the dead, the subtle reference to mortality from Rimmer’s painting is laid bare and made immediate by the new medium of photography.

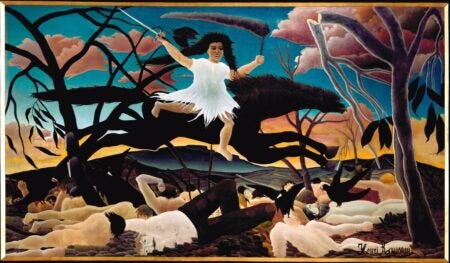

Henri Rousseau. War. 1898. Oil on canvas. Image and data from SCALA, Florence.

Toward the end of the 19th century, the self-taught French painter Henri Rousseau reacted to the violence of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, social unrest, and enforced conscription in La Guerre, his stark declaration against war. When the apocalyptic six-foot canvas was exhibited at the Salon of 1894, the catalog described it in words that echo Rubens above: ‘War; she passes terrifyingly, leaving despair, tears, ruin all around.’ Toward the end of his life, Rousseau confided in a friend: “When a king declares war, immediately mothers must protest and stop him from doing it.” 2

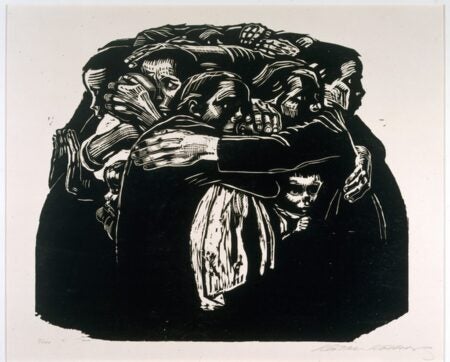

Käthe Kollwitz,.1922-1923. Die Mütter (The Mothers), from the series Krieg (War). 1922-1923. Woodcut. Image and data from Smith College Museum of Art.

Henri Cartier-Bresson. France. Paris. Peace demonstration. 1945. Photograph. ©Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos.

Käthe Kollwitz’s series of seven woodcuts entitled Krieg (War) published in 1924 and represented here by The Mothers is a testament to the depth and despair of grief for those left behind by the victims of war — the tragic aftermath. The artist lost her own son Peter at the beginning of WWI, days after his arrival at the Front in Belgium. His namesake and her grandson later died in service in WWII. In a letter to the boy’s mother, Kollwitz exposed her renewed pain: “Every war is answered by a new war, until everything, everything is smashed.” 3

The anguish left by World War II is clearly captured by photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson in the face of a woman in a line of peace demonstrators in Paris in 1945, where the dark mass of people recalls the cluster of mothers in Kollwitz’s woodcut. Cartier-Bresson, the co-founder of the Magnum photography cooperative, experienced war as a French soldier, working for the Underground on assignment, and as a prisoner of war.

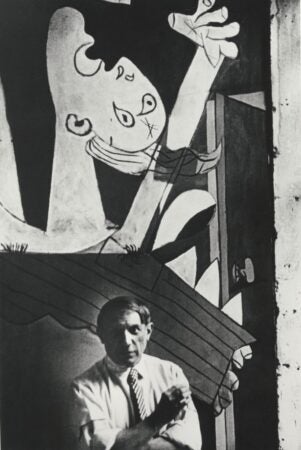

David Seymour. Pablo Picasso and Detail of Guernica, France, 1937. Photograph. Image and data from the Center for Creative Photography.

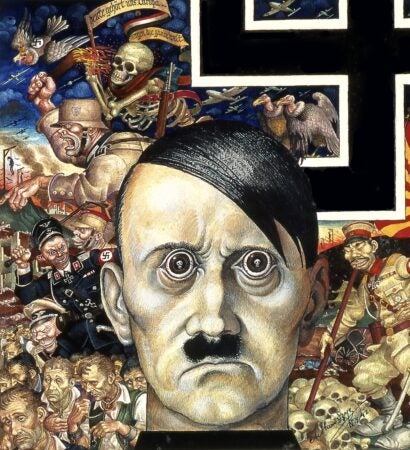

Arthur Szyk. Anti-Christ. 1942. Watercolor. Image and data from Irvin Ungar.

On April 26, 1937, the Basque town of Gernika was firebombed by German-led Fascist forces, killing hundreds of defenseless citizens. The event ignited the wrath of Pablo Picasso who had been musing on a theme for a commission for the Spanish pavilion at the World Exhibition in Paris. From May to early June, he created Guernica, massive — 25 feet long — monochrome, and mesmerizing (shown here in detail in a photographic portrait of the artist). Owing a debt to Rubens’ Consequences of War, and Goya’s work, the painter unleashed his singular artistic language to render the fragmented chaos and savagery of the attack. While Picasso was immersed in the tragedy in Spain, the writer Michel Leiris presciently saw in Guernica the near future of Europe: “On a black and white canvas that depicts ancient tragedy… Picasso also writes our letter of doom: all that we love is going to be lost…” 4

Polish-born American painter and caricaturist Arthur Szyk devoted much of his work to satirizing and belittling the actions of wartime tyrants, notably Hitler, the Japanese emperor Hirohito, and the Italian dictator Mussolini. In minutely described illustrations that exploited the technique of manuscript illumination, he mocked the political bullies of WWII, as in the watercolor Anti-Christ, a portrait of Hitler, that was reproduced as a magazine cover for The Answer with the warning “This is Germany.”

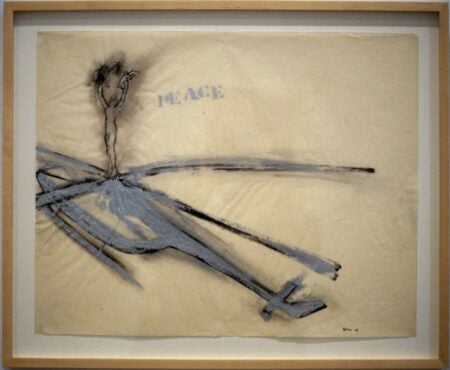

Nancy Spero. Peace. 1966. Gouache and ink on paper. Image and data from Larry Qualls.

Nancy Spero. Peace. 1966. Gouache and ink on paper. Image and data from Larry Qualls.

The events of the Vietnam war provoked outrage in New York activist artist Nancy Spero, who stated: “I thought the terminology and slogans like ‘pacification’ coming out of the Pentagon were really an obscene use of language. ‘Pacification.’5 They would firebomb whole villages and then the peasants would be relocated into refugee camps.” From 1966 to 1969, she made around 150 gouache paintings on paper entitled The War Series, featuring sexualized war machines disgorging violence. The two near-mirror images displayed here show a triumphant figure of peace rising over a downed helicopter and a murderous helicopter expelling destruction.

Susan Meiselas. El Salvador. El Mozote. The Memorial at El Mozote. The plaque reads, “They did not die, they are with us, with you and with all humanity.” 1991. Photograph. ©Susan Meiselas / Magnum Photos.

American photographer Susan Meiselas was establishing her portfolio around human rights issues in Latin America when she was one of the first journalists to witness the outcome of the El Mozote massacre in El Salvador during the Civil War in 1981. The entire village was obliterated and hundreds were murdered. Ten years after the attack, Meiselas made a photograph of the memorial in the town, a haunting silhouette of a family with clasped hands. Her title includes the inscription on the monument: “They did not die, they are with us, with you and with all humanity.”

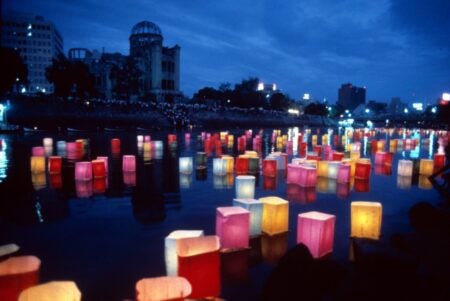

Philip Jones Griffiths. Japan. Hiroshima. Lanterns float on a river on the anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb. 1995. Photograph. ©Philip Jones Griffiths / Magnum Photos.

In 1995, the Welsh-born photographer Philip Jones Griffiths, best known for his documentation of the Vietnam War, made a series of pictures marking the fiftieth anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, including the lantern ceremony shown here. The Toro Nagashi (lantern floating) in Hiroshima, enacted every year on the anniversary of the detonation of the first atomic bomb, guides the souls of the dead. Against the backdrop of the skeletal silhouette of the Genbaku Dome, one of the only remaining buildings—as shown in the photograph—it also signifies peace and lends hope that the unthinkable will never happen again.

— Nancy Minty, Collections Editor

1 For the original letter in Italian, see Printed copy (Rooses and Ruelens) on Bibliothèque de l’INHA, Paris. For a translation see Kristin Lhose Belkin. Rubens (London, 1998), pp. 298-299.

2 In a statement recorded by Wilhelm Uhde, in Henri Rousseau, 1911, quoted in: Fae Brauner, Contesting “Le Corps Militaire”: Antimilitarism. Pacifism, Anarcho-Communism and ‘Le Douanier” Rousseau’s La Guerre. RIHA Journal/0048/24 July 2012.

3 Käthe Kollwitz. The Diary and Letters of Käthe Kollwitz. (Hans Kollwitz, Editor). 1988.

4 Russell Martin. Picasso’s War: The Destruction of Guernica, and the Masterpiece That Changed the World, 2003. See also Rhodes, R. (2013). Guernica: Horror and inspiration. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 69(6), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096340213508672, and A. Kopper, (2014). Why Guernica became a Globally Used Icon of Political Protest? Analysis of its Visual Rhetoric and Capacity to Link Distinct Events of Protests into a Grand Narrative. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 27(4), 443–457. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24713306.

5 Michael McNay. Nancy Spero, obituary. The Guardian, Oct. 23, 2009.

Collections on JSTOR

- Scala Archives

- Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Smith College Museum of Art

- Magnum Photos

- Center for Creative Photography

- Arthur Szyk

- Larry Qualls Archive: Contemporary Art