Chasing the New Year around the globe

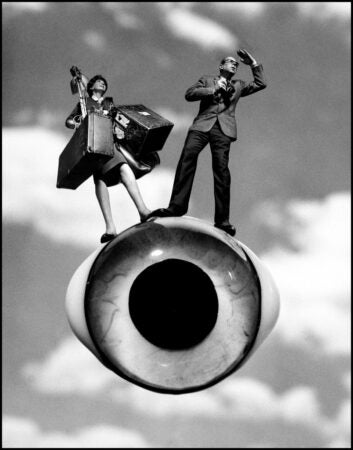

Philippe Halsman. Philippe and Yvonne HALSMAN New Years Card… c. 1960. Photograph. © Estate of Philippe Halsman / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Magnum Photos.

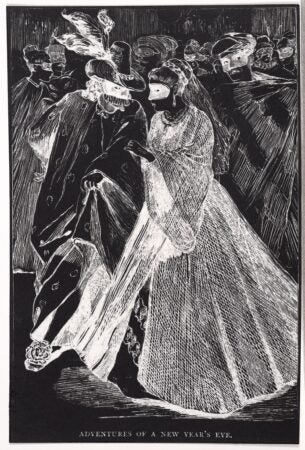

Winslow Homer. Adventures of a New Year’s Eve. Negative photostat. Image and data from Smith College Museum of Art.

The New Year is an enduring phenomenon that generates celebrations of varied traditions across the world and throughout the calendar. It is our sincere wish that you may partake of these festivities in good health and with hope for the coming year. Please join us in honoring these holidays of renewal for 2023.

North America, the geolocation of Artstor/ITHAKA is our point of departure. January 1, the first day of the modern Gregorian calendar, is commemorated here by a zany card by photographer Philippe Halsman, c. 1960, a send-up of his craft, and a bewitching print from a bygone era by Winslow Homer, Adventures of a New Year’s Eve.

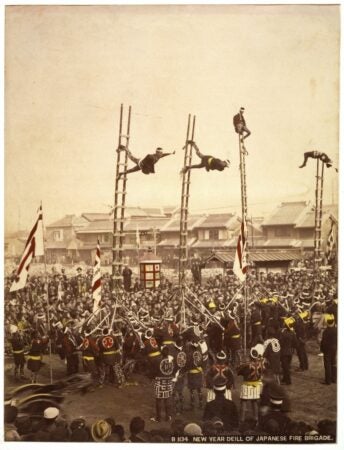

In 1873, Japan converted from the lunar to the Gregorian calendar, synching its New Year to the countries of the West. One of the ancient rituals that became aligned to the new date was dezome shiki — to be marked this coming year on January 6 and illustrated here in a hand-tinted photograph from c. 1890. Literally the “ceremony of the year’s first excursion,” the holiday highlights the firefighting skills and acrobatics of ladder brigades going back to the period when Edo (Tokyo) was plagued by devastating fires.

- Kimbei (Japanese, 1841-1934). ca. 1890. New Year Deill [sic] of Japanese Fire Brigade. Albumne print with color. c. 189o. Image and data fromGeorge Eastman House.

- Kano school. A Screen for the New Year: Pines and Plum Blossoms. 1600. Mineral pigments, ink and gold leaf on paper. Image and data from the Worcester Art Museum.

- Chris Steele-Perkins. Japan. Tokyo. New year lights in Shinjuku. 2005. Photograph. ©Chris Steele-Perkins / Magnum Photos.

- Patrick Zachmann. France. Paris. Chinese New year. 13th arrondissement. 1998. Photograph. ©Patrick Zachmann / Magnum Photos.

We may revisit the lunar holiday in Japan with the radiant gold-leaf Screen for the New Year, 1600, featuring pine and plum blossoms, both symbolic of the nascent year. A contemporary photograph, New Years lights in Shinjuku, 2005, contrasts a modern view of the holiday, January 1, with the traditional pine transformed to a decorated Christmas tree.

Chinese New Year, celebrated for more than three millennia, remains firmly entrenched in the lunar calendar. It occurs on January 22 in 2023. The holiday is observed throughout the world, as exemplified by the vivid scene photographed in the Paris suburb of Ivry, 1998.

In the Chinese zodiac, followed also in Japan and much of Asia, the year 2023 is represented by the rabbit or hare, based on a twelve year cycle represented by twelve animals. Those born under this sign are said to be fortunate, discrete, long lived, and peaceful. The moonstruck rabbits depicted in a Chinese embroidery and a Japanese woodcut exemplify the stable characteristics attributed to the sign.

Qing Dynasty. Rabbit in Landscape with Clouds, Moon, Two Constellations, Rocks, Bamboo, Flowering Shrubs… . 1736-1795. Album Leaf, silk on silk. Image and data from The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Free reuse (CC0).

Hiroshige. Untitled (Two Rabbits, Pampas Grass, and Full Moon). c. 1849-1851. Color woodcut. Image and data from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The Tibetan lunar calendar features Losar (from lo meaning year and sar, meaning new) that straddles a couple of days of the old year and several of the new as it announces the end of winter. It is an ancient ritual that dates back to the Bon people, and is the most important holiday for Tibet and other Himalayan countries. The Ch’am dances, pictured here by a fierce masked participant, signify the victory of good over evil, and are performed by monks.

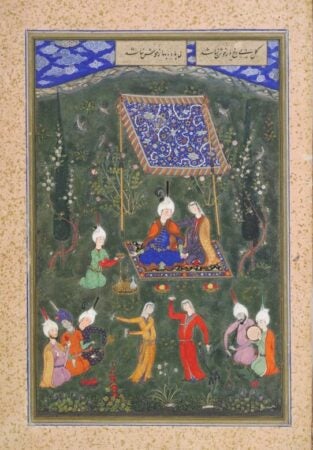

The ancient Persian New Year, also a rite of spring, is called Nowruz, which means new day. It occurs March 21 to 22, 2023, coinciding with the vernal equinox and reaching back to Zoroastrianism. It is celebrated in Iran and across the Silk Roads countries of central Europe. A lively 16th-century miniature of a spring picnic, by the gifted Safavid painter Sulṭān Muḥammad, pays tribute to the festive delights of the season.

- Rob Linrothe. Guomar (sgo dmar) monastery. New year’s ch’am (masked dance), detail. 2002. Photograph. Image and data from Skidmore College.

- Attributed to Sultan Muhammad. Lovers’ Picnic, detail, folio from the Divan of Hafiz. c. 1530. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. Image and data from Harvard Art Museums.

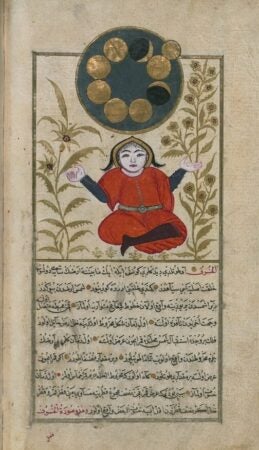

- Author: Zakariya ibn Muhammad Qazwini/Scribe: Muhammad ibn Muhammad Shakir Ruzmah-‘i Nathani. Formation of the Crescent of the Moon, detail. 1121 AH/AD 1717 (Ottoman). Illuminated manuscript, ink and pigments on European laid paper. Image and data from The Walters Art Museum.

The Hijri New Year — also known as Islamic New Year — begins on July 19 this year and runs for nearly all of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar based on the lunar year. It commemorates the Hijra (migration), the journey of the prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Medina. The occasion is initiated by the sighting of the crescent moon. An illumination — The formation of the crescent moon — c. 1717 highlights the lunar phenomenon. It is part of an Ottoman manuscript that reprises the beloved work of the medieval Persian cosmographer and geographer Zakarīyā ibn Muḥammad Qazwīnī, entitled Wonders of Creation.

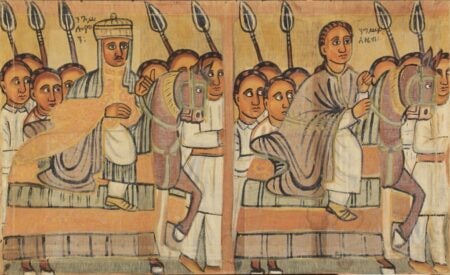

Unknown artist, Ethiopian. Procession of Solomon and Sheba. Oil on linen. Image and data from Binghamton University Art Museum.

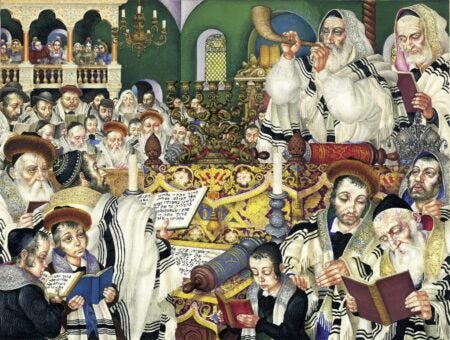

Arthur Szyk. Rosh Hashanah, from The Holiday Series. 1948. Watercolor and gouache on paper. Image and data from Irvin Ungar.

The Ethiopian New Year, Enkutatash, which means gift of jewels, occurs on September 12, 2023, the first day of Meskerem, the first month of the calendar. It marks the end of the rainy season when the country blooms with the yellow flowers of Adey Abeba. The celebration commemorates the visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon in Jerusalem in ancient times, as shown in a painting depicting their procession. When the Queen returned to her land she was met with jewels, known as enku.

Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, follows on September 15 to 17, the beginning of the month of Tishrei, commemorating the creation of the world. The “first” or “head” of the year segues into the Days of Awe, a time of introspection that ends with Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. A watercolor by Arthur Szyk, 1948, illustrates a busy congregation blessing the day, including the ritual of the blasting of the shofar (ram’s horn).

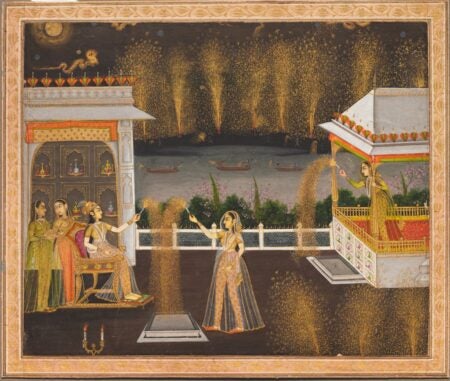

We end our round of New Year’s rites with Diwali, which will begin on November 12, 2023. The brilliant festival of lights is observed throughout India and many other parts of the world. Diwali derives from the Sanskit terms dipa for lamp and vali for row — proclaiming the victory of light over darkness where celebrants illuminate their temples, houses, and rivers. The spectacle is illustrated here by a miniature featuring a revelry illuminated by shimmering lamps, sparklers, and fanciful fireworks.

Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow. Ladies Celebrating Diwali. c. 1760. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Image and data from The Cleveland Museum of Art, Free reuse (CC0).

— Nancy Minty, Collections Editor

Collections on JSTOR