Women behind the lens:

photographers in the field

Eve Arnold on the set of Becket. 1963. Photograph by Robert Penn. © Eve Arnold / Magnum Photos.

“It is the photographer, not the camera, that is the instrument. ” – Eve Arnold

In honor of Women’s History Month we are celebrating the brave sisterhood that influenced the early years of photojournalism, and its successors who have shaped the fields of social and environmental documentary photography. The journey begins in the mid-nineteenth century with the birth of photography, flourishes in the analog boom years of print, and rises again with digital technology. In the words of photojournalist Yunghi Kim, it is the spirit of “visual storytelling” that unites the mission.

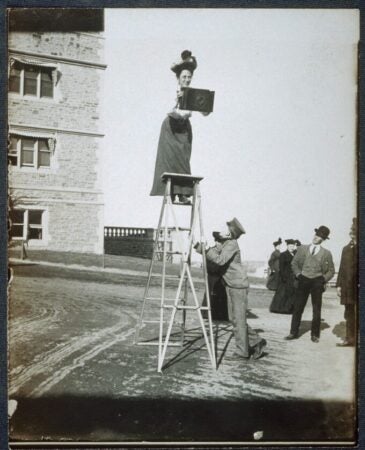

- Unknown. Beals standing on top of a ladder, holding her camera. 1904. Photograph. Image and data from The Schlesinger History of Women in America Collection.

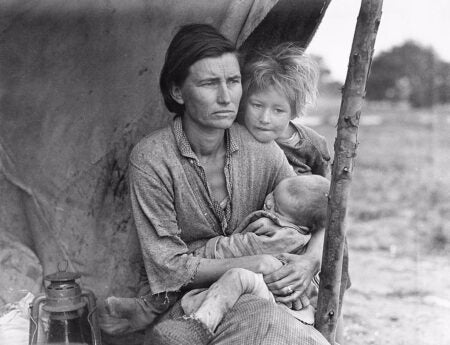

- Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother. 1936. Photograph. Image and data from Vincent Virga and the Library of Congress.

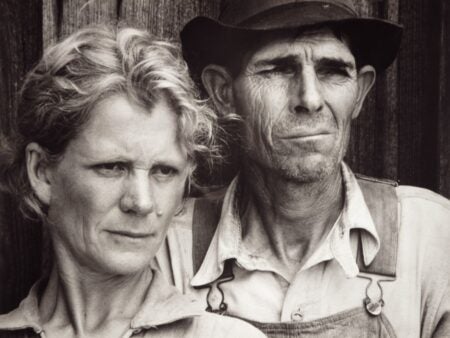

- Margaret Bourke-White. Maiden Lane, Georgia. c. 1936. Photograph. Image and data from The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Women photographers were recognized for their work in the field long before the term photojournalism was coined at the University of Missouri in the 1940s. Jesse Beals Tarbox, shown here on assignment at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, perched on a ladder behind an outsized camera, was the first recognized woman in news photography. Dorothea Lange is acclaimed for her Farm Security Administration photographs, including the series Migrant Mother, 1936. She received a foundation in Pictorial photography from Arnold Genthe at the Clarence H. White School. She went on to work for the government in the 1940s and was later hired by Life, traveling to Asia, South America, and the Middle East.

Professionally trained in the 1920s and a contemporary of Lange, Margaret Bourke-White was the first foreign photographer to work in the Soviet Union, the only westerner to document the German invasion of Moscow and one of the first photojournalists to be embedded with air crews and the liberators of the concentration camps in Germany during World War II. She is also known for images of the hardships of the Depression era, as seen in the double portrait shown here. The German photographer Gerda Taro died in the field in 1937 in an accident during the Spanish Civil War. At the age of 26, she was the first female photographer to die “in action,” underscoring the tragic association between photojournalism and war at mid century.

- Eve Arnold. 1961. Malcolm X. 1962. Photograph. © Eve Arnold / Magnum Photos.

- Eve Arnold. China. Second Trip. 1979. Photograph. © Eve Arnold / Magnum Photos.

- Inge Morath. New York City. Anthony Truly, drag queen aerobics instructor at Crunch Gym. 1997. Photograph. ©Inge Morath / Magnum Photos.

- Martine Franck. Prague. Ancient Jewish cemetery. 2004. Photograph. © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos.

- Cristina Garcia Rodero. Spain. Photograph. © Cristina Garcia Rodero / Magnum Photos.

Three courageous women led the field of photojournalism in the aftermath of World War II: the American-born Eve Arnold, her Austrian friend Inge Morath and, somewhat younger, Martine Franck from Belgium. They were among the first female members of Magnum Photos, the cooperative agency founded in 1947 by four battle-hardened photographers. In a world less traveled these women brought home scenes, spectacles, people, and phenomena that were unreachable to most. Arnold’s prolific career with Life, The Sunday Times, Magnum, and in photographic books, is summarized here by a portrait of Malcolm X, 1961, and a shot of equestrian acrobats in Magnolia, 1979, demonstrating the intimacy of portraiture and the portrayal of a people.

In 1995, she was honored with the award of Master Photographer by the international Center of Photography—even after all of her accomplishments, the ultimate prize for a woman was still titled “master.” Morath’s introduction to the field developed through journalism and as a picture editor. She committed to photography through Magnum and work with Life, Paris Match, and other publications. Her sustained contribution to the field is captured in more than a dozen books shot throughout the world. Her sensibility is revealed in the portrait of Anthony Truly, 1997. The writer Philip Roth described Morath as: “a tender intruder with an invisible camera.”

Martine Franck pursued print commissions and became a Magnum member in the 1980s, however her narratives intimate social documentation rather than traditional photojournalism, as pictured in the Ancient Jewish cemetery, 2004. Spain’s Cristina Garcia Rodero, also a Magnum member, further explores the ethnographical/cultural aspect of documentary photography, sometimes deploying humor alongside inquiry, as in her study of a boy and a statue.

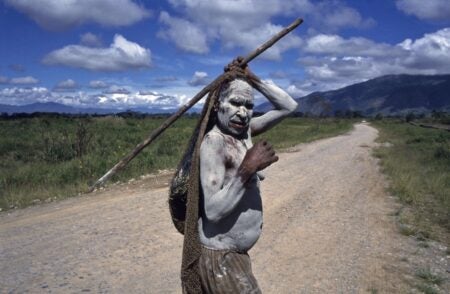

- Susan Meiselas. Indonesia. Irian Jaya. Dani Tribe. 1989. Photograph. © Susan Meiselas / Magnum Photos.

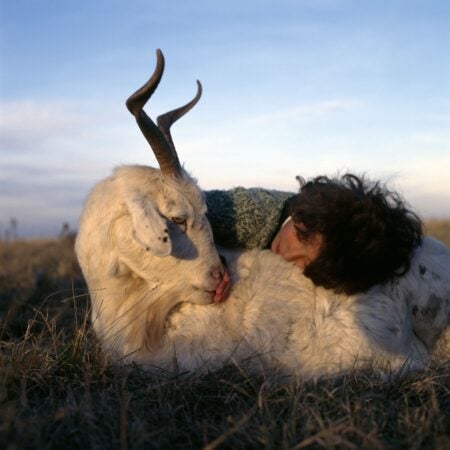

- Alessandra Sanguinetti. Argentina. Buenos Aires. “The Adventures of Guille and Belinda,” Belinda with Rosita. 1998. Photograph. © Alessandra Sanguinetti / Magnum Photos.

- Carolyn Drake. Washington, DC. January 20, 2017. Inauguration Day for Donald Trump. Photograph © Carolyn Drake / Magnum Photos.

- Carolyn Drake. Washington, DC. January 21st, 2017. Women’s March. Photograph © Carolyn Drake / Magnum Photos.

The photography of Susan Meiselas and her work leading the Magnum Foundation towards greater diversity shine a bright light for women in the field. Meiselas documented conflict and war in Nicaragua and El Salvador, as well as genocide against the Kurdish people in Northern Iraq, in several books. Her documentation takes in archive, film work, and collaborative installations, and she wields her craft as a tool for social change. In 1989, she photographed a Dani traveler in West Papua, shown here. New generations at Magnum have further diversified the visual narrative tradition. American-born Alessandra Sanguinetti, raised in Argentina, has used photography as a means to probe relationships—those of domestic animals and their keepers and the sustained entente between two of her growing cousins. Her themes are intimate but they reveal larger truths, like the tender human-animal bond in an image from “The Adventures of Guille and Belinda,” 1998.

Carolyn Drake has used photography and other media to interpret and subvert accepted narratives in sustained projects and books set in Asia, Russia, and the United States. Two views from Washington, D.C., January 20-21, 2017 encapsulate the poles around Donald Trump’s inauguration and the historic Women’s March. Mexico/Brazil-based Spanish photographer Cristina de Middel shifted from photojournalism to conceptual/documentary work when she became disillusioned with the promise of “truth.” Her work plays on the margins between reality and fiction, as in her headless portrait of a sitter on a beach, 2020.

The urgency of climate concerns has taken hold in the work of documentary photographers like the Russian/German Nanna Heitmann and the Canadian-born Czech Iva Zimova, a member of the London-based Panos Pictures agency: wildfire smoke in Siberia clouds a portrait of a girl and a coiled hose symbolizes relief from drought in Afghanistan.

- Cristina de Middel. Brazil. Itacaré, Bahía. 2020. Photograph. © Cristina de Middel / Magnum Photos.

- Nanna Heitmann. Siberia. Sayana at a wedding, while the air is covered with smoke from the neighboring wildfires. June 2021. Photograph. © Nanna Heitmann / Magnum Photos.

- Iva Zimova. A man carries a bundle of plastic hose which will be used to irrigate a pistachio orchard. 06/01/13. Photograph. © Iva Zimova / Panos Pictures.

The Panos agency, affiliated with an NGO in development, is a leader in documenting global social issues, reflecting the changing mission of photojournalism. The Montana-based documentarian Ami Vitale was an early member of the Panos collective. She has worked in well over 100 countries on humanitarian stories. Currently she favors an environmental focus in her work, sometimes defined as conservation photography. She summarized her approach: “Today, my work is not just about people. It’s not just about wildlife either. It’s about how the destiny of both people and wildlife are intertwined and how small and deeply interconnected our world is.” The interconnection runs through her considerable oeuvre and it may be sensed in just two images capturing the gaze of a harvester and the eye of an elephant.

It is impossible to do justice to all of the women who have enriched the fields of photojournalism and documentary photography here. We encourage you to search and gather your own inspiring selection.

– Nancy Minty, collections editor

Ami Vitale. Guddi Bai Verma gathers wheat during the harvest. 2005. Photograph. © Ami Vitale / Panos Pictures.

Ami Vitale. An elephant. India and its sacred elephants are being threatened by deforestation… 2004. Photograph. © Ami Vitale / Panos Pictures.

1. www.evearnold.com

2. Kim chronicles the field in Trailblazers of Light, documenting the work of hundreds of female photojournalists and picture editors, mostly in America. See also The Authority Collective, an inclusive cooperative.

3. Morath, Inge. Portraits. New York: Aperture Foundation, 1986.

4. Note re diversity org/note re women still in small numbers

5. Phil Mistry. Ami Vitale: From Photographer to Conservationist, Dec. 12, 2022.

Artstor collections