Earth Day: For the birds

Louis Agassiz Fuertes, bird portraitist

Louis Agassiz Fuertes with a live Snowy Owl. c. 1920. Photograph. Image and data from Louis Agassiz Fuertes Papers, Archives, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

April 22 marks the 53rd anniversary of Earth Day, the birth of the modern environmental movement. This year we honor the day and the intent with a tribute to the bird portraitist Louis Agassiz Fuertes, born in 1874, nearly 100 years prior to Earth Day, in Ithaca, New York. The artist’s father, Estevan Antonio Fuertes, was a Puerto Rico-born professor of civil engineering at Cornell University. Louis’ early passion for the meticulous study of birds, his artistic skill, and the support of his mentor Elliott Coues, an ornithologist at the Smithsonian, denoted the beginning of a life devoted to birding and the artistic record of the many feathered species. Throughout his life Fuertes participated in scientific/artististic expeditions from Alaska and Siberia, throughout the United States and Canada, to Mexico and Columbia, and finally, Ethiopia.

From a body of work that encompassed more than a thousand field and studio sketches, the artist created finished paintings and illustrations that were included in foundational birding publications of the era: Citizen Bird, 1897; Birds of New York, 1910; National Geographic 1913-1920; Birds of Massachusetts (1925-1929).

Thanks to an open collection from the Cornell University Library – Laboratory of Ornithology Gallery of Bird and Wildlife Art, we are able to glimpse Fuertes’ artistic awakening in studies made during his teens and early twenties and preserved in intimate sketchbooks.

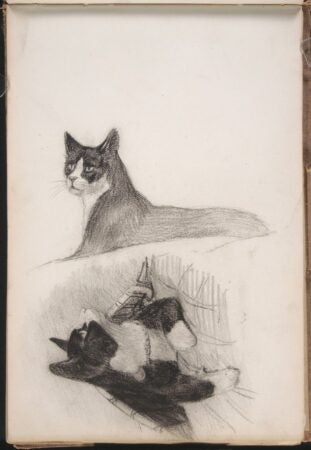

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Cats. c. 1895. Charcoal on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

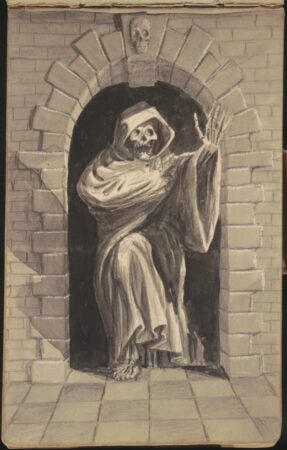

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Skeleton in Doorway. c. 1892. Watercolor and pencil on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

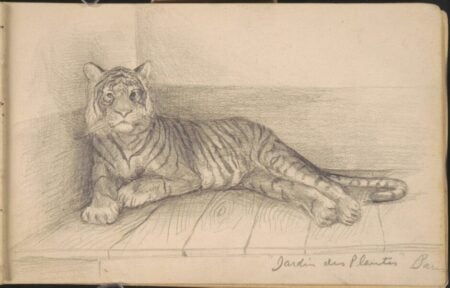

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Jardin des Plantes Paris. c. July 1892. Pencil on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

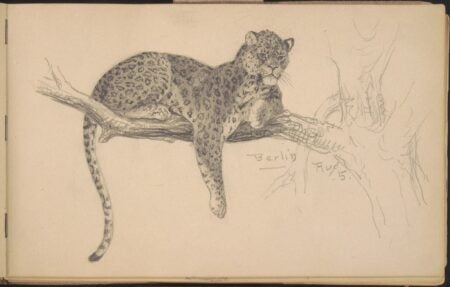

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Leopard in Berlin. August 5, 1895. Pencil on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

While a watercolor of a skeleton rising from a doorway and charcoal vignettes of lounging cats, completed before Fuertes was 21, do not predict his passion for the birds, they do announce his promise as a draftsman. In 1892, the 18-year-old aspiring artist accompanied his parents to Europe. While his young colleagues might have been found sketching at the Louvre or the Rijksmuseum, Fuertes apprenticed by studying wildlife at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, and again in 1895 at the zoos in Berlin, Dresden, and Brussels. Two pencil sketches, a tiger from Paris, 1892, and a leopard from Berlin, 1895, demonstrate a respect of the big cats and the artist’s tendency to endow his animal renderings with the distinctive characterization of portraits.

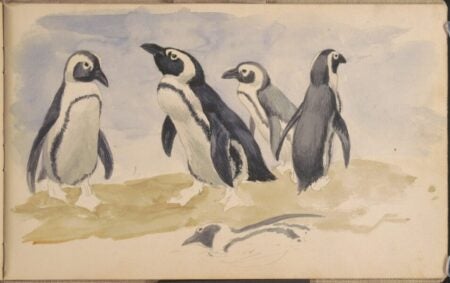

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Penguins. Drawings. c. 1895. Watercolor and pencil on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

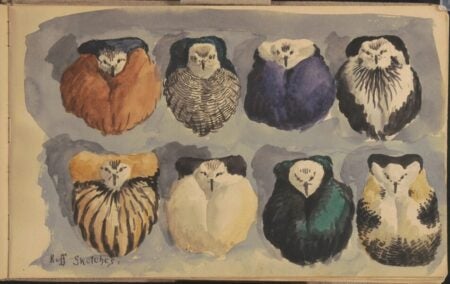

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Ruff Sketches. c. 1895. Watercolor on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

A freely executed watercolor of gamboling penguins was probably also captured at a zoo, while the Ruff Sketches, both c. 1895, presents a decorative double frieze of songbird specimens.

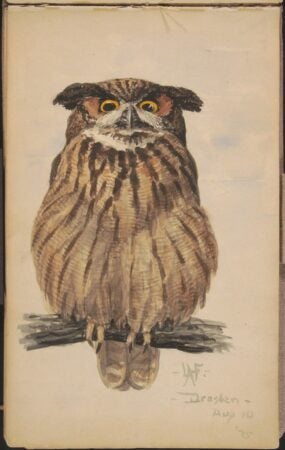

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Owl in Dresden. August 10, 1895. Watercolor on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

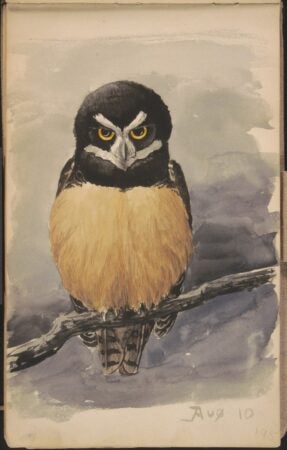

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Spectacled Owl. August 10, 1895. Watercolor on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

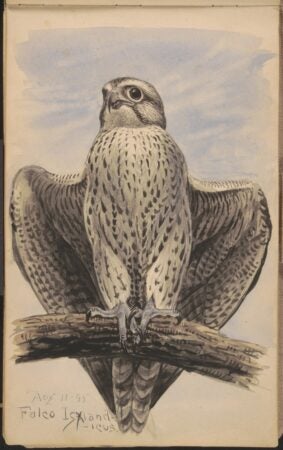

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Falco Islandicus. August 11, 1895. Watercolor on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

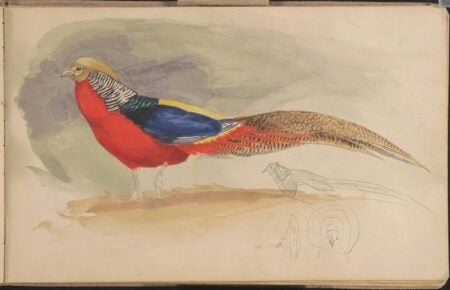

No animal is better suited to portraiture than the owl, and these distinctive subjects appear to have been favorites of the artist. Two of his early watercolors, each depicting a horned and a spectacled owl date from c. 1895 while he worked in Dresden. His Iceland Falcon completes a triad of birds of prey. A lively page of robust finches and a resplendent golden pheasant crown the selection of Fuertes’ European sketches and his nascent period as an artist.

- Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Golden Pheasant. c. 1895. Watercolor and pencil on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

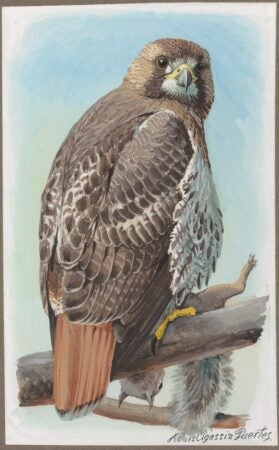

Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Red-tailed Hawk (#19). 1920s. Watercolor. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

Louis Agassiz Fuertes. Black-capped Chickadee. 1897. Watercolor on paper. Image and data from Cornell University Lab of Ornithology Art Collection.

We conclude with two works that represent Fuertes’ prolific career as an illustrator: the Black-capped chickadee, 1897, a crisp monochrome watercolor from a series of more than 100 finished works that the artist produced as illustrations for the children’s book Citizen Bird by Mabel Osgood Wright and Elliott Coues; and an imposing red-tailed hawk who seizes our gaze as he grips his prey—a watercolor from the 1920s when Fuertes was commissioned to paint 90 bird portraits to be produced as “collector cards” and enclosed in Arm & Hammer Baking Soda boxes.* The cards popularized birdwatching and promoted conservation, and they bore the admonition “For the Good of All, Do Not Destroy the Birds.” Happy Earth Day and give thanks for the birds!

– Nancy Minty, collections editor

* Notably, about 10 of the illustrations of the birds of prey weren’t published until 1976 since the predators were considered contrary to public favor.