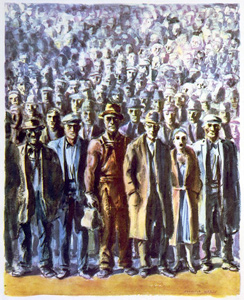

Katsukawa Shunsho | The actors Ichikawa Danjuro V as a skeleton, spirit of the renegade monk Seigen… | Edo period, 1783 | The Art Institute of Chicago | Photography © The Art Institute of Chicago

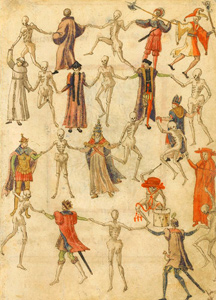

Some blocks in my neighborhood are getting downright spooky – front yards are filling with spider webs and tombstones, and ghosts peek through the bushes. Along with the piles of pumpkins and inevitable candy corn appearing in the supermarket, they are a reminder that Halloween is just around the corner. Americans celebrate Halloween on October 31 by trick-or-treating, displaying jack-o’-lanterns (carved pumpkins) on their porches or windowsills, holding costume parties, and sharing scary stories.

Halloween stems from the Celtic harvest festival of Samhain (roughly, “summer’s end”) held on October 31–November 1, when people would light bonfires and wear costumes to ward off roaming ghosts. The festival was integrated into All Saints Day, a Catholic holiday observed on November 1 to honor saints and martyrs. The evening before All Saints Day was referred to as All Hallows’ Eve, which eventually became Halloween.

Day of the Dead figurine, skeleton dog | 2002 ca. | Mexico | Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology

In countries with Roman Catholic heritage, All Saints Day and All Souls Day (November 2) have long been holidays in which people commemorate the departed. The tradition in my native Mexico is known as Día de los Muertos, “Day of the Dead,” and celebrations take place on the first two days of November, when family and friends gather to remember loved ones who have died. Similar to the evolution of Halloween, the celebration conflates the Catholic holidays with an Aztec festival dedicated to a goddess called Mictecacihuatl, the “Lady of the Dead.” I have fond memories of visiting the cemetery with my family to clean my grandfather’s grave and play with the children of other visiting families. People in Mexico often build altars using brightly decorated sugar skulls, marigolds (popularly known as Flor de Muerto, “Flower of the Dead”), and the favorite foods and beverages of the deceased. I was particularly fond of the sugar skulls; I always tried to bite into them, but they tend to be so hard that I would have to ask my father to break mine with a hammer.

Multiple Carvers | John Sanders; Hannah Saunders, 1694 | Salem, Massachusetts | Image and data From: The Farber Gravestone Collection, American Antiquarian Society

Many Latin American countries hold similar celebrations, with some colorful regional differences: In Ecuador, the Day of the Dead is observed with ceremonial foods such as colada morada, a spiced fruit porridge, and guagua de pan, a bread shaped like a swaddled infant; in addition to the traditional visits to their ancestors’ gravesites, Guatemalans build and fly giant kites; and in Brazil, Dia de Finados(“Day of the Dead”) is celebrated on November 2.

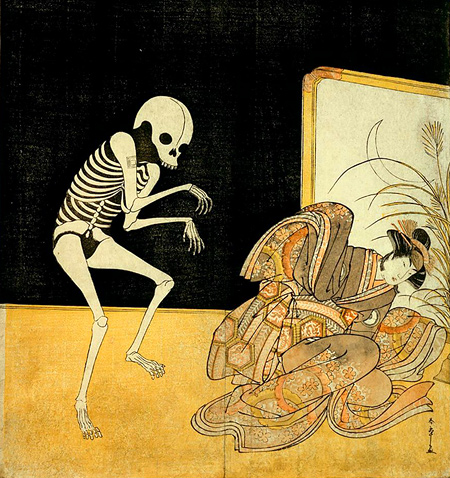

German School | Dance of Death | 16th century | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

To help you celebrate the season, there are thousands of suitably macabre images in the Artstor Digital Library. A great starting point is the Farber Gravestone Collection (American Antiquarian Society), which contains more than 13,500 images of early American grave markers, mostly made prior to 1800. You can also do a search for “Day of the Dead” to find images of calacas, skeleton toys from Mexico. There are also some artists who were great at portraying the dark side: You may be familiar with Henry Fuseli’s famous “Nightmare,” but a simple search of his name leads to several equally scary works, including a different version of the painting and several prints with the same theme; a search for caprichos will lead you to Francisco Goya’s legendary series of prints, rife with witches, demons, and gloomy owls, and a search for Goya witches to a set of his most unsettling paintings and etchings; similarly, search Baldung witches to see a number of the German Renaissance painter Hans Baldung’s ghoulish drawings, or search for his name to see his famous “Death and the Maiden”; and a search for Jose Guadalupe Posada will result in the Mexican artist’s famous “Calaveras,” satirical engravings of skeletons popular during the holiday.

Is this getting a little too dark for you? Try Hine pumpkin to see cheerier photographs by legendary documentary photographer Lewis W. Hine.

Book of Hours. Use of Rome; Folio #: fol. 072r | 16th century, second quarter | Image and original data provided by the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

What are you afraid of? Find something to keep you up at night with this list of our spookiest posts: