A guide to Medieval creepy crawlers

…and how to protect yourself from them

While there were a lot of delightful beliefs about animals in the Middle Ages (our favorite: hedgehogs roll on grapes to spear them on their spines so they can take them home to their young), this Halloween season we’re focusing on the creepiest creatures of all: reptiles! Not to worry, we’ll also tell you what to do to stay safe from them.

Our source for this guide is Richard Barber’s translation of the Bodleian Library’s MS Bodley 764, a mid-thirteenth century bestiary, so don’t be too surprised if the descriptions deviate just a tad from contemporary herpetology.

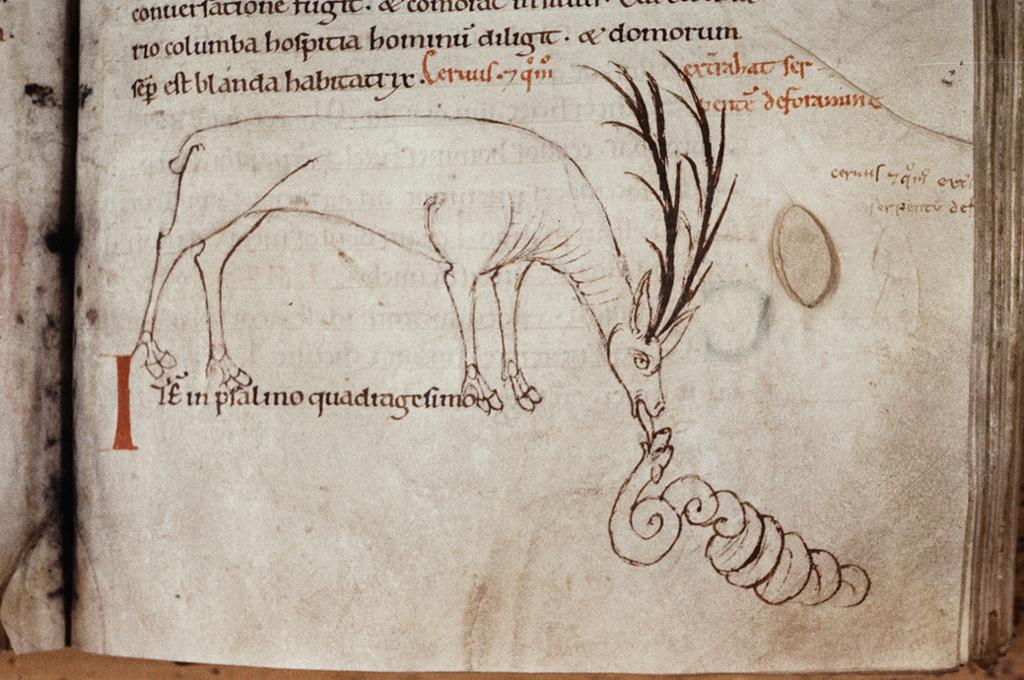

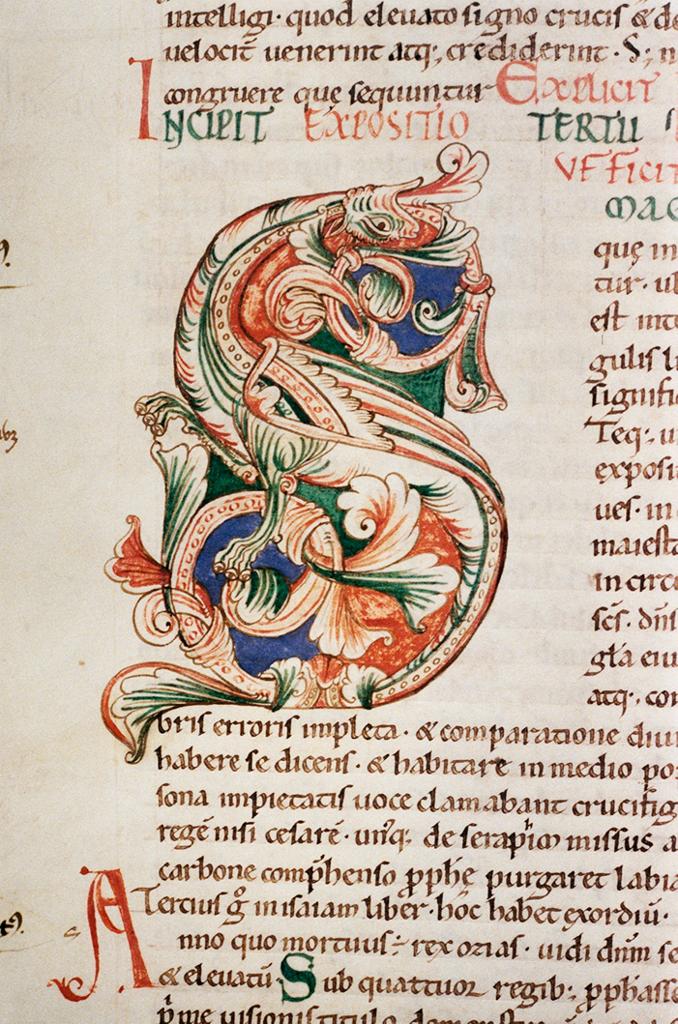

Bestiary. Folio #: fol. 160r, 12th century. Image and original data provided by the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

Let’s start with plain old snakes. We bet you didn’t know that snakes are frightened by naked men, but attack clothed ones. Unfortunately our source doesn’t specify how snakes respond to women (the thirteenth century not being the most progressive of centuries), so your best bet is to keep a stag nearby, as they can handily deal with bothersome serpents.

French, Medallion with Man Fighting Basilisk, ca. 1240-60. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 ; 17.190.2149

As a rooster with a snake’s tail, we’re not sure whether the basilisk can technically be considered a reptile, but it is called “the king of creeping things.” It destroys birds at a distance with its fiery breath, and will “kill a man simply by looking at him.” Protect yourself by carrying a weasel with you, as that is the only animal that can kill a basilisk.

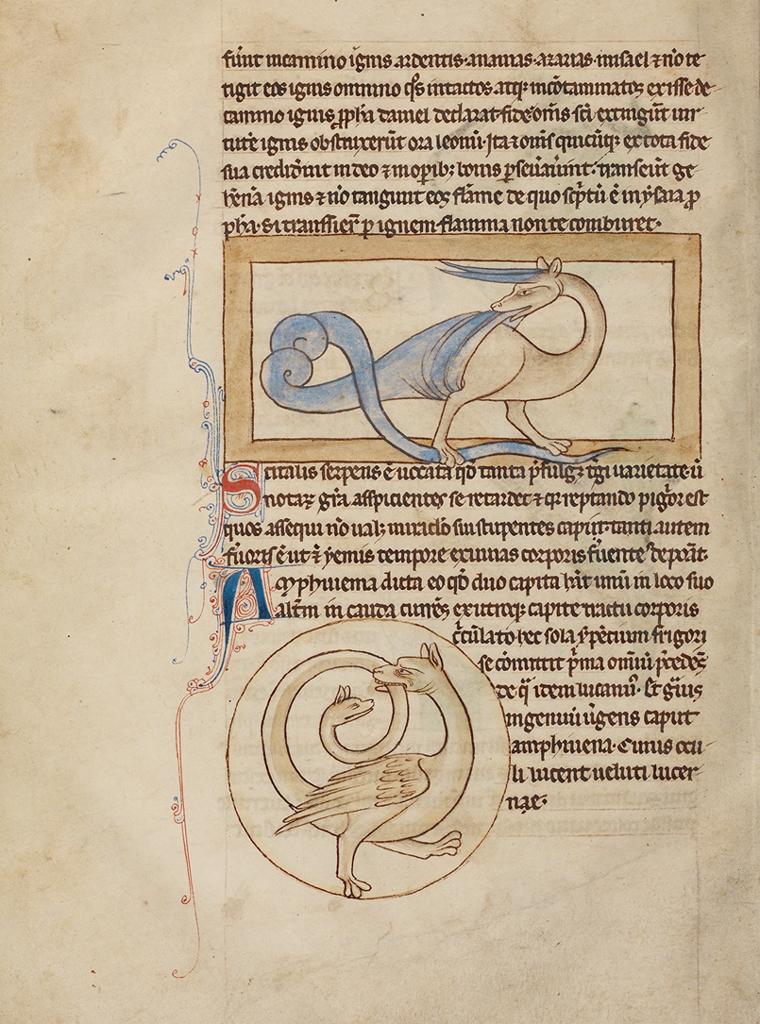

Unknown creator, A Scitalis, An Amphisbaena, c. 1250 – 1260. Image and original data provided by The J. Paul Getty Museum www.getty.edu

The scitalis (top), being “too lazy to pursue its prey,” attracts its victims with such a brightly-colored back “that all creatures that approach it slow down to admire its splendor.” Our advice: keep moving.

Not so pretty, the amphisbaena (bottom) is a snake with a head on both ends. Thanks to its unique physique, it can run in either direction without having to turn around! Just steer clear.

Unknown creator, Cerastes, 1497. The Illustrated Bartsch. Vol. 90, commentary, German Book Illustration through 1500: Herbals through 1500.

The cerastes is a snake with ram-like horns. It hides in the sand so that only its “fourfold growth” (don’t ask) shows to attract animals, which are then killed. The cerastes also bites the heels of horses to knock off their riders. Avoid mysterious growths on the ground.

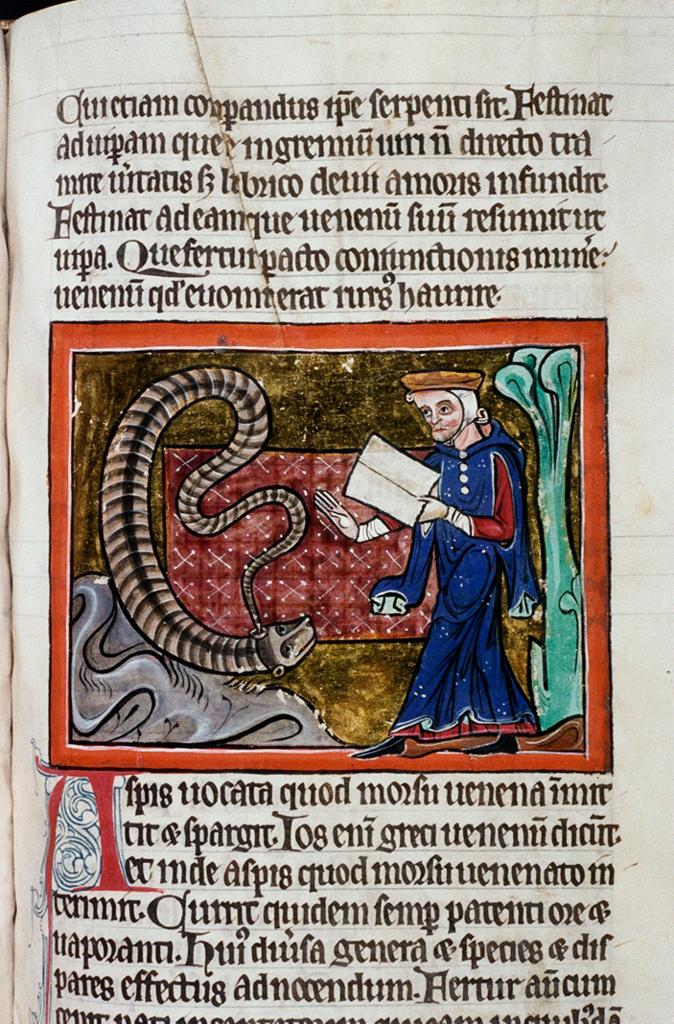

Bestiary. Folio #: fol. 096r, 13th century. Image and original data provided by the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

The asp, which “moves with its mouth open and steaming,” is probably the cleverest of all serpents because it avoids being enchanted with music by pressing one ear against the ground and plugging the other with its tail. You’re on your own with this one.

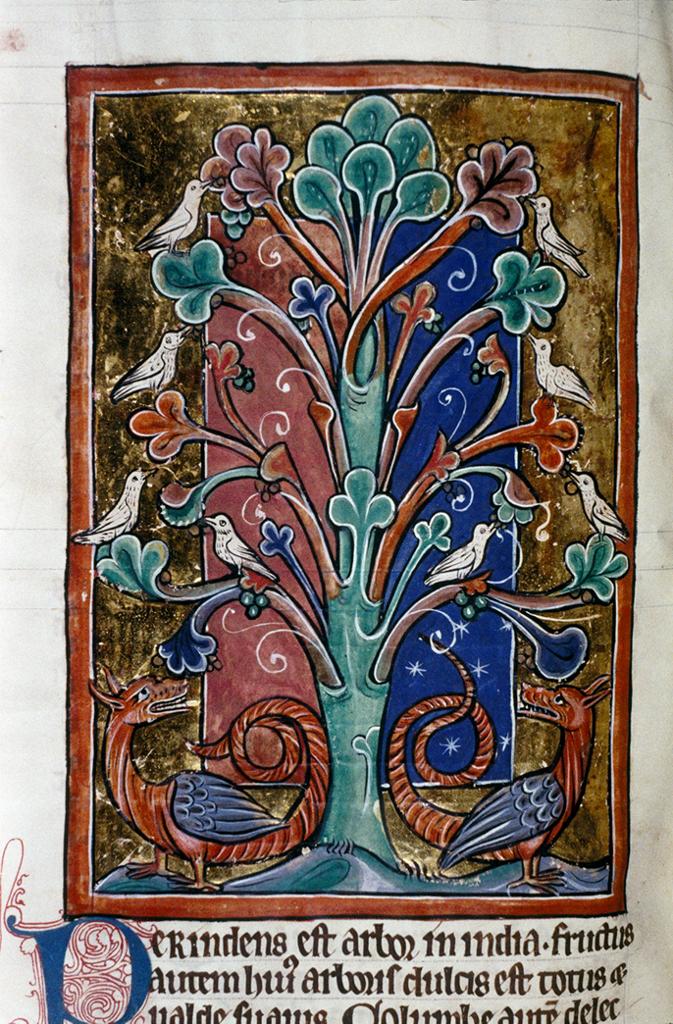

Bestiary. Folio #: fol. 091v, 13th century. Image and original data provided by the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

The dragon is the largest of all living creatures, and no animal knows its dangers better than its number one enemy, the elephant. Dragons hide near paths where elephants walk, entangle their feet with their coils, and suffocate them. As you can see in this picture, dragons also have a taste for doves! Luckily for the doves, dragons fear the perinden tree, so consider planting one outside of your house… if you can figure out what they are.

Jerome, Commentary on Isaiah. Folio #: fol. 031v, 11th century. Image and original data provided by the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

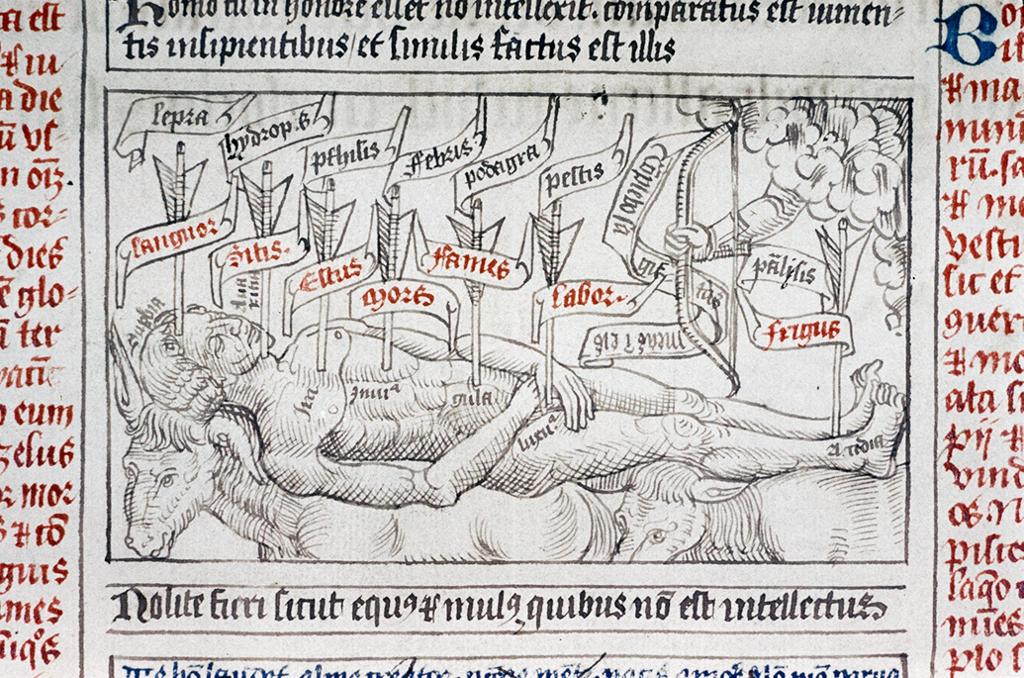

You have to feel a little sorry for the viper. To reproduce, the male sticks its head in the female’s mouth, which she then bites off in ecstasy. And breeding is not just a bad deal for the males: when the female is pregnant, the offspring “do not await their natural release in good time” and bite their way out, killing the mother. Our advice: leave them be, it sounds like they’ll end up destroying each other eventually.

Joos van den Hecke, Poems. Folio #: fol. 012r (Roman), before 1538. Image and original data provided by the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

And finally, the dipsa is a snake so small you can’t see it before stepping on it, and so poisonous you die before even feeling the bite. It’s so very tiny we couldn’t find an example among the 2.5+ million images in the Artstor Digital Library, but that doesn’t mean it’s not there. We can’t help you with this one, as this guy will testify.

Want to see more marvelous animals? Search for bestiary in Artstor–we guarantee it’s worth it, with hundreds of colorful, fantastic selections from the Bodleian Library and other collections. But for goodness’ sake, whatever you do, watch out for the dreaded bonnacon!

– Giovanni Garcia-Fenech

You may also be interested in: