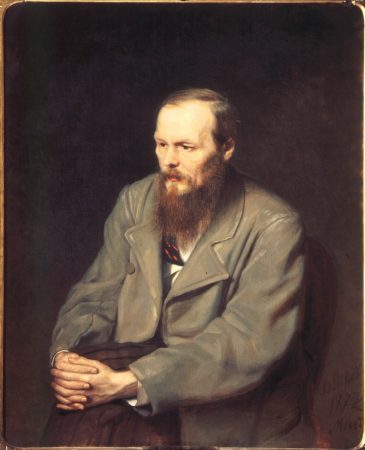

Vasily Perov. Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky. 1872. Image and original data provided by SCALA, Florence/ART RESOURCE, N.Y., artres.com, scalarchives.com

More than 3 million of the images in Artstor are now discoverable alongside JSTOR’s vast scholarly content, providing you with primary sources and vital critical and historical background on one platform. This blog post is one of a series demonstrating how the two resources complement each other, providing a richer, deeper research experience in all disciplines.

In August 1867, shortly after Fyodor Dostoevsky married his stenographer Anna Snitkina, the couple headed to Geneva. As much as a honeymoon, they were also fleeing family tensions and hounding by Fyodor’s many creditors. On the way, the newlyweds stopped in Basel for a day and visited its museum. It was there that the famed writer of Crime and Punishment had an unsettling encounter with an artwork that would soon appear in one of his most esteemed novels.