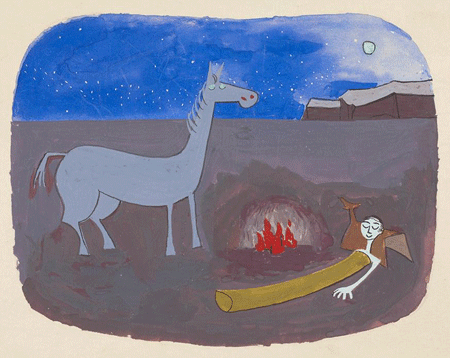

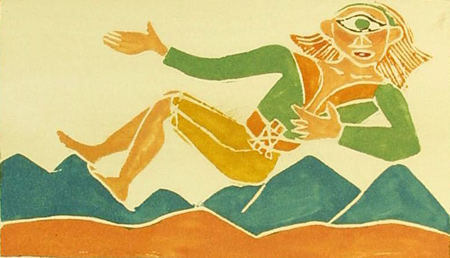

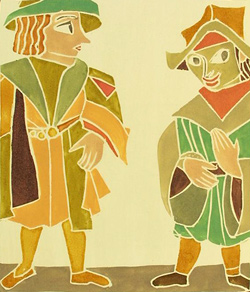

Rem Koolhaas, Madelon Vriesendorp, Elia Zenghelis, Zoe Zenghelis | Exodus, or the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture: The Strip, project Aerial perspective, 1972 |The Museum of Modern Art, Architecture and Design Collection | © 2007 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / BEELDRECHT, Hoofddorp, NL

We’ve gathered six examples that illustrate how the images in Artstor can be used to enhance the teaching and learning of architecture and architectural history, along with two case studies, one by a then-doctoral candidate and another by a fine art faculty member.

In his four decades as an architect and urbanist, Rem Koolhaas has never wavered in his audacious vision, continuously dreaming up controversial projects such as the Central China Television Headquarters Building in Beijing (composed of two uneven 44-story legs joined at the top by a 13-story angled bridge that precariously juts out over a plaza), or an unrealized proposal for a 1.5-billion-square-foot Waterfront City on an artificial island just off the Persian Gulf in the coast of Dubai.